SWOT Analysis of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine

December 1, 2025

By Maxwell C. Shull and Harvey S. Hahn, MD

Executive Summary

This issue provides a comprehensive SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis of artificial intelligence (AI) in medicine. It highlights how AI can enhance efficiency, reduce clinician burnout, improve diagnostic accuracy, and support quality improvement, while also emphasizing challenges such as bias, hallucinations, the “black box” problem, and cybersecurity risks.

- Ambient listening and automated documentation can reduce note-writing time by more than 20% and cut after-hours work by 30%, helping mitigate burnout.

- New medical AI systems demonstrate high accuracy in complex cases, offering support for pattern recognition, risk prediction, and early detection that can enhance primary care decision-making.

- AI tools can simplify discharge instructions, translate languages in real time, and draft patient messages, improving comprehension and reducing communication barriers.

- AI can calculate stroke, bleeding, and other risks instantly, supporting evidence-based management of common conditions, such as atrial fibrillation.

- Primary care clinicians must recognize that AI inherits the biases of its training data (garbage in = garbage out), including racial, gender, and publication bias, and, therefore, requires human oversight.

- AI may provide confident but incorrect answers; clinicians should verify outputs, especially when used for clinical reasoning or patient communication.

- Tools such as digital twins, AI-assisted pre-charting, and wearable-integrated predictive models eventually may enable highly personalized, real-time primary care.

Artificial intelligence (AI) stands to be one of the most disruptive forces in medicine for the foreseeable future. It has affected and will continue to

affect efficiency, quality, safety, and provider burnout. The market size of AI in healthcare was estimated at $26.69 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow to $613.81 billion by 2034.1 To best use AI, medical professionals must understand its strengths and weaknesses as well as its potential. Any review of AI is fraught with problems, the most relevant being the likelihood of becoming irrelevant shortly after publication. Understanding this, we will attempt to review AI in the context of a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis as a framework to understand where we are and where we could go with AI.

What Is SWOT?

The SWOT system was first used at Lockheed’s Corporate Development Planning Department in the 1950s. Robert Franklin Stewart, while at the Stanford Research Institute, promoted the so-called SOFT (satisfactory, opportunity, fault, and threat) approach that, in 1967, eventually morphed into the SWOT analysis.2 Since that time, it has become a staple of organizational review and strategic planning. Although there are many other reviews of AI in the literature, we feel that this approach will provide an easy-to-follow skeleton for discussing the very fluid topic of AI in medicine. (See Table 1.)

Table 1. SWOT Matrix of AI in Medicine |

Strengths

Weaknesses

Opportunities

Threats

|

SWOT: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats; AI: artificial intelligence; GIGO: garbage in = garbage out |

Strengths of AI

Enhanced Efficiency and Decreased Burnout Through AI

One of the main benefits of technology is the promise of making human life easier. AI already has made an impact on documentation through passive ambient AI listening and note generation. This is an important area, since it affects not only efficiency but also physician burnout, which is a serious issue.3 Electronic medical record (EMR) documentation adds hours to providers’ workdays, while adding little value to care and increasing burnout. In fact, in a survey of 1,253 healthcare workers done by the American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA), 75% thought that EMR documentation impeded patient care.4 In the same survey, 77.4% also thought that EMR documentation added significant time to the workday, often requiring taking work home, thus disrupting work-life balance. Objectively, a study tracking actual time spent found that ambient AI scribing reduced note writing time by 20.4% and after-hours work by 30.0%.5 Another reason EMRs lead to burnout is the lack of meaning doctors feel when completing all the required documentation.6 Most doctors feel the most engaged and happy when operating at the top of their abilities.7 This is such a problem that the AMIA, along with other health organizations, put together a plan to reduce the documentation burden to 25% by 2025, the so-called “25x5” plan — AMIA 25x5: Reducing Documentation Burden.8 Ambient listening already has made a positive impact in this area. In a study of 1,430 clinicians conducted at Mass General Brigham and Emory, burnout was reduced from 50.6% to 29.4% in just 42 days of use (P < 0.001) that persisted up to 84 days later.9 In this same study, the proportion of users rating their well-being as a 3 or a 4 (positive or very positive, respectively) improved from 1.6% to 32.3%

(P < 0.001).

Large language models (LLMs) using passive listening already have been widely deployed and studied with effects on time efficiency and burnout. According to a 2024 survey done by NextGen and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), 42% of health organizations already use an iteration of ambient AI.10 If your organization is not using this AI technology already, you already are significantly behind. AI will affect all healthcare stakeholders. (See Table 2.)

Table 2. Stakeholder Perspectives on AI | ||

Stakeholder Group | Optimism/Perceived Strengths | Concerns/Perceived Weaknesses |

Physicians | Reduces documentation time and administrative burden, improves diagnostic accuracy, enhances work efficiency | Effect on patient-physician relationship, patient privacy, change in workflow and habits |

Patients | Potential for efficiency and fewer errors in diagnostics, improved convenience from chatbots, earlier and faster medical care | Lack of transparency and consent, data privacy and security, erosion of human empathy |

Hospital Executives | Efficiency, improved safety, improved quality, cost savings | Data privacy and security, algorithm bias limitations, lack of a clear implementation strategy |

AI: artificial intelligence | ||

Not only can AI interpret test results, but it is able to send a message to the patient explaining those same results. AI can draft the message and, in an early study of 344 messages (half generated by healthcare professionals and half generated by AI), the AI-generated explanations were rated as better, and even more empathetic than typical doctor responses.11 This also can positively affect burnout by decluttering doctors’ EMR inboxes.

Quality Improvement Through AI

A goal shared by all stakeholders is to improve the safety and quality of medical care; AI is well-suited to help, not to take over, physicians in doing this. An important foundational barrier is language. AI can help in several facets of difficult communication.

AI can literally translate spoken language, thus helping reduce this common, critical barrier.12 A study compared ChatGPT-4 and Google Translate across 50 specific emergency department instructions translating English to Spanish, Chinese, and Russian. The translated instructions then were back-translated and double-checked by physicians. The accuracy of both programs was more than 90% for Spanish and Chinese, and above 80% for Russian. The potential harmful mistakes were less than 6% for both across all three languages.

This application of AI suggests the idea of a “universal translator” as seen in the Star Trek television series; this is not far from reality now. Apple recently announced that the iPhone 15 (or later models) paired with AirPods and Apple Intelligence can translate several languages in real time.13 In fact, two people with similar Apple devices can have a conversation in real time, each speaking a different language while hearing in their own language.

Furthermore, AI can simplify information, removing the typical medical jargon and abbreviations doctors inadvertently use, to help patients better understand their treatment plans, especially at discharge.14 In this study, out of 100 discharge summaries evaluated, 54% received the top rating, but 18% had safety concerns. An important feature of this study was that AI was not used to grade the generative AI discharge summaries; instead, two experienced physicians were the gold standard.

AI is not in competition with humans. A business study demonstrated that the lower-performing workers using AI assistance had the greatest increase in productivity (43%) compared to high-performing workers.15 The high performers also improved, but only by 17%. Furthermore, those who chose not to use AI arrived at the correct answers 19% less often than those who did use AI. AI has the potential not only to improve each individual’s quality of care but also to raise the overall level of medical care in our profession.

An example of this is that Open Evidence AI scored 100% on all three parts of the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE). An initial trial was conducted using ChatGPT-4 with 1,300 Step 1-style questions; the model answered 86% correctly.16 A recent AI tool, Semantic Clinical Artificial Intelligence (SCAI), developed at the University of Buffalo, completed Step 3 with an accuracy of 95.1%. Open Evidence AI is a curated AI that only searches published articles and has working agreements with the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) and the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

Enhanced Diagnostics Through AI

A feature of AI that is objectively superior to humans is attention span (humans now are down to an average of eight seconds), indefatigability, and the ability to handle multiple points of data.17

An important example of this is a study using AI to help determine the best treatment for glioblastoma.18 It took seven weeks to sequence the glioblastoma. A total of 8,449 mutations were found, six of which had available actionable therapies. IBM Watson reviewed all the research on these factors in 10 minutes. It was estimated that it would take 160 hours of human effort to review the same amount of data. However, Watson missed one protocol that could have treated two of the mutations simultaneously because the protocol was not yet published; that protocol was identified by a human doctor.

A recent paper by Microsoft used 304 diagnostically complex cases from the NEJM’s clinicopathological conferences and fed them into their new MAI-DxO AI.19 It achieved 85.5% diagnostic accuracy compared to general internal medicine doctors scoring a 20% diagnostic accuracy.

A particularly exciting study developed a specific medical AI called Delphi-2M, which was trained on more than 400,000 participants in the U.K. Biobank and then validated on more than 100,000 U.K. Biobank patients and a Danish databank of 1.9 million.20 Delphi-2M was used to predict the occurrence of more than 1,000 ICD-10 diagnoses up to 20 years in the future. The overall area under the curve (AUC) was 0.76, which outperformed other tested static prediction modes; however, the AUC for prediction of death was 0.97, regardless of gender.

Not all AIs are built the same. In a study comparing five LLMs, including two medical-domain models (Clinical Camel and Meditron), AI performed significantly worse than physicians.21 The AI models had diagnostic accuracies from 64% to 73%, while physicians scored 89% accuracy. This variance highlights the difference between being able to pick the single best answer on a multiple-choice test (e.g., the USMLE) and making a difficult clinical diagnosis. The five models tested were all open-source, free AI models and most likely were not as robust as the specific medical AI programs noted earlier.

AI typically is considered unbiased in its approach. A large-scale study using machine learning (ML) to predict outcomes in coronary artery disease patients is an excellent example of this.22 The study looked at more than 80,000 patients. It compared 27 expert-selected variables to more than 600 AI-selected variables. The AI model outperformed the expert-generated multivariant model, which makes sense given 600+ variables to analyze vs. only 27. It is interesting to note that of the 27 expert-selected variables, only seven made it into the ML top 20. Age and smoking status were two of the strongest predictors in the ML model, but the third was diuretic use. This makes sense, since this could be related to worse left ventricular function, clinical heart failure, or renal dysfunction, all of which commonly are accepted as high-risk clinical features. However, most clinicians would not independently identify diuretic use as a risk factor.

Using ML, the Geisinger health system analyzed 171,510 patients and 331,317 echocardiograms.23 Age obviously was the most prognostic variable, but the second strongest predictor was not ejection fraction — it was tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity. At first glance, this would seem counterintuitive, but on further reflection, this also makes sense. The higher a patient’s tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity, the higher their pulmonary artery pressures. This most likely represents longer standing and worse left ventricular dysfunction. The ML model also outperformed the Framingham Risk Score and the American College of Cardiologists/American Heart Association guideline score, increasing the area under the receiver operator curve to 0.89.

One of the chief jobs of a doctor is to assess the risks and benefits of any potential disease along with its potential tests and treatments. This clinical assessment is one reason why older, more seasoned doctors are more sought out and trusted than younger, less experienced doctors.

Many doctors use risk scores to advise patients on their expected risks of surgery (pre-operative surgical risk assessment) or other treatments, but many rely on experience and gestalt. Why do more doctors not use risk scoring when it is so readily available? There are two main reasons: It takes time to calculate those scores and doctors like to fall back on heuristics (mental shortcuts) to lump patients’ risks into categories (low, intermediate, or high; no one is at no risk). Nevertheless, why would doctors not want a more precise estimate of risk if a method is readily available?

The most likely explanation derives from Daniel Kahneman’s framework of System 1 and System 2 thinking, for which he received the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics.24,25 System 1 is fast, automatic, and heuristic-driven; it guides approximately 95% of our daily judgments. In contrast, System 2 is slow, deliberate, and cognitively effortful and, therefore, engaged far less frequently. As a result, clinicians often default to experiential shortcuts rather than analytic reasoning. For example, a single negative experience with a used car may lead an individual to dismiss all future offers as scams. Similarly, a patient’s prior adverse reaction to penicillin may prompt unwarranted avoidance of all penicillin-based antibiotics. Even the death of a patient during surgery may bias clinicians against recommending similar interventions despite evidence of benefit. These reactions illustrate how System 1 can override more rational, System 2 processing. Recognizing this tendency highlights the importance of slowing down and engaging in deliberate reasoning when navigating complex medical decisions.

For example, consider a patient who comes into the clinic with new atrial fibrillation. Should we start anticoagulation in this specific patient? To best advise this patient, the doctor would have to calculate their stroke risk using one of the many available CHA2DS2-VASC calculators. Additionally, the doctor also should assess bleeding risk by calculating their HAS-BLED score. There also is a growing volume of literature on the benefits of calculating the net clinical benefit.26-29 This, too, would lead to additional calculations. Conducting this series of calculations for every atrial fibrillation patient quickly becomes overwhelming for a busy clinician. An obvious solution is to delegate the necessary arithmetic to AI, which also would be able to produce the risk of stroke, bleeding, and net clinical benefit before the doctor even enters the room.

The next step not only will be to assess risk, but also for AI to suggest treatment options. A recent example of this is the ePRISM system to reduce contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) post-angiography. ePRISM is an ML AI that evaluates risk and provides dye load recommendations to operators to reduce CIN. In early studies, it has been shown to reduce CIN from 10% of cases to 2.18% (P < 0.0001). This represents a 78% reduction in CIN. Bleeding rates also were reduced from 2.15 cases per month to 1.54, and length of stay was reduced from 3.44 days to 1.79 days.30

Weaknesses of AI

Two major factors make us believe in the superiority of AI: the ability to compile data from a large data set and a lack of intrinsic biases. In medicine, we are taught statistical terms, such as regression to the mean, skewed data, outliers, and Gaussian distributions, that all typically are improved with the size of the data set. Additionally, AI does not make decisions based on intrinsic biases (recall System 1 thinking mentioned earlier); therefore, its conclusions will be free from them. Surprisingly, AI can be biased as well.

An important mantra in medicine is “garbage in = garbage out,” now denoted as GIGO by the AI community. Attending physicians typically say this at the beginning of a rotation, informing medical students, interns, residents, and fellows that the quality of their assessments is dependent on the quality of information they are presented with during rounds. This also is true for AI. Although AI can search through a large dataset (PubMed database) quickly, there is a well-known bias that equally affects AI and humans: publication bias.

Publication bias is the fact that investigators typically send in only manuscripts that have a positive result. Few papers supporting the null hypothesis are submitted and/or published. This also affects meta-analysis. If only positive studies are submitted and published about a certain drug or test, meta-analysis typically will amplify the results. This has been demonstrated in a comparative study of initial meta-analytic reviews and later well-designed, large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Forty primary and secondary endpoints were compared across 12 large scale RCTs and 19 meta-analyses addressing the same clinical questions. The meta-analysis only correctly predicted the actual result of the RCTs 68% of the time.31 As a result of this, there is a renewed emphasis on publishing negative trials to get them into the medical literature.

The best, and most disturbing, example of GIGO is the Reddit experience with AI. A team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) strictly taught their AI from a narrow, deep, and dark subsection of Reddit. The learning engine then was shown basic Rorschach blots and instructed to report what it perceived. The AI, dubbed Norman Bates after the main antagonist in the movie Psycho, gave disturbing, death-related, and morbid answers.32

A particularly odious type of bias in medicine is racism. Since 2020, the NEJM has called on medical societies to remove race from their clinical algorithms.33 Recently, NEJM reported on the five-year progress.34 Eight out of 13 clinical tools had race removed. The journal Science published the rationale behind these types of efforts, calling them “exclusion cycles.”35 The phenomenon described occurs when non-medical social situations, such as race, become self-reinforcing cycles, making people in that minoritized group typically appear less healthy and, often, less likely to receive appropriate care. This, in turn, introduces and reinforces racial bias.

A final example of AI bias is Amazon’s attempt to replace their human resource department with AI.36 In this instance, the AI model had been taught using resumes from the past 10 years. AI was found to be categorically downgrading female applicants, since the vast majority of past employees were male. Resumes with phrases such as “women’s captain” were downgraded, in addition to applicants who stated they had graduated from an all-women’s college. This project ultimately was scrapped.

Although these examples highlight the broad spectrum of algorithmic bias, an even more pressing concern is their potential to undermine health equity. If unmonitored, AI systems can encode and perpetuate existing disparities under the disguise of objectivity, effectively embedding structural inequities into an opaque “black box.” Because clinical algorithms influence diagnosis, triage, and treatment pathways, physicians and health systems must actively demand transparency, robust auditing tools, and equity-focused performance metrics. We, as physicians, should ensure that AI models improve care for marginalized populations rather than magnify historical bias.

The most important weakness of AI is hallucinations. AI hallucinations are when AI returns an invalid answer, purely for the sake of producing a response. The most famous example of this phenomenon was IBM Watson’s final Jeopardy answer in 2011. Although the engine still won the game, it had incorrectly answered “What is Toronto?” to the final Jeopardy question.37 The final Jeopardy question in the category “U.S. Cities” was, “Its largest airport is named for a World War II hero; its second largest for a World War II battle.” The correct answer was “What is Chicago?” referencing O’Hare and Midway airports. A recent paper by Open AI outlines the source of the issue, which may lead to potential solutions.38 AI can generate a response, but it is not incentivized to return an uncertain answer. Rather, it is incentivized to guess, even though it is not sure of the correct answer. Since AI is graded by accuracy and informed that there is no inherent penalty of producing a faulty response, AI guesses.

AI’s occasionally partisan reasoning and apparent guesswork have led to an excellent review article discussing the proper use of AI.39 This review was written from the perspective of educators teaching medical trainees but also speaks to the lay public’s need to vet any summary or result garnered from AI. Just as we should supervise trainees’ use of AI, we need to hold ourselves to these same standards. Similar advice can be given for vetting any and all material seen on social media.

Opportunities

Potential AI opportunities parallel AI’s strengths. This section is organized along with the same two topics referred to previously. However, with the rapid pace of AI’s growth, these two sections will only scratch the surface of AI’s potential and possibilities.

Enhanced Efficiency and Decreased Burnout Through AI

The next obvious step beyond passive listening and dictation is asking questions and giving orders. How often do we check Google or UpToDate in the room with a patient? Soon, we should be able to relay questions and orders to AI by voice command. These possibilities resemble Marvel Studios’ Tony Stark using his AI assistant through his AI-enabled glasses (Jarvis, Friday, and E.D.I.T.H.). Someday we all could have an AI digital assistant with us that is more powerful, and useful, than any scribe. In fact, that future already is here.

Meta (the parent company of Facebook) recently released AI-supported Ray-Ban and Oakley sunglasses.40 The glasses, equipped with speakers, a microphone, and camera, are capable of listening and responding to the wearer. You can ask Meta AI such questions as, “Where am I,” “What artwork am I looking at,” “What building is this,” or “What famous person is this” and it will tell you. The latest version has a heads-up display and wrist controls.41

Instead of asking these types of travel-based questions, we could ask, “What is the optimal dose of this antibiotic for this patient?” or “Which lipid-lowering medication would be best for this patient, given their overall lipid panel?” or “Which hypertensive program would be ideal for this patient with these co-morbidities?”

An obvious next step with ambient AI is automatic coding and ordering based on your conversation with the patient. This would further decrease or offload cognitive stress from doctors.42 ChatGPT 4.0 was used in a nephrology simulation and assigned the correct diagnosis code to 99% of cases.43 It soon will be feasible for physicians to complete the history and physical, documentation, coding, ordering, and billing all verbally, in a fraction of the time.

Not only can AI help you complete your note, but it also can prepare it — a task known as pre-charting, which often is time-consuming and labor-intensive. A small study evaluated eight LLMs to gather relevant information on a patient. The results for AI were 45% at least equivalent and 36% were superior to routine chart review. Promisingly, the pre-charting, which took doctors seven minutes on average, was completed by AI in a few seconds.44

AI also is capable of responding to preferences set by the user. For pre-charting, AI automatically can collect any new labs and studies from the last visit and summarize any admissions or specialist visits since, incorporating them into your note. Or, in an instance concerning a common, repetitive diagnosis, AI could greatly reduce the time it takes to process it. Consider amiodarone monitoring for atrial fibrillation. A simple vocal prompt such as, “Initiate amio protocol” would inform AI to order pulmonary function, liver, and thyroid testing, and refer to an ophthalmologist for eye exams, scheduling these appointments on a serial basis until the medication is stopped.

Another frustrating and time-consuming area in medicine is acquiring prior authorization for tests and procedures and fighting insurance denials. AI promises to help in all aspects of the revenue cycle by decreasing time and freeing up staff to provide clinical care, rather than making phone calls or filling out forms.45 However, payors also are using AI, which could lead to a “bot vs. bot” exchange to decide payments. This undoubtedly will incentivize access to a more powerful learning engine.

Opportunities for Quality Improvement Through AI

With limited access to specialists, especially in more rural locations, AI-equipped glasses could be used similarly to telemedicine for the rapid evaluation of possible stroke.46 A specialist could interview and examine a patient remotely to decide whether they need a higher level of care. To this end, AI could be extended to the routine office encounter, overreading echocardiograms, chest X-rays, and skin lesions to help decide whether an emergency department visit or referral is warranted. In an ideal future, physicians could request a real-time, virtual consultation with a specialist as they talk through AI glasses, allowing the specialist to have access to lab results and examine the patient through the camera.

An interesting study demonstrated the utility of AI in providing real-time assistance during procedures. AI helped decide which lesions to biopsy during a colonoscopy. AI used 312 distinct imaging features after being trained on 61,925 biopsy-proven lesions. A notable finding in this study was that using AI added, on average, only 0.4 seconds to the procedure.47

Smartphones are a potential way to move medical care to the home. Most smartphones come equipped with excellent cameras. These cameras could be used to accurately diagnose skin cancer. Instead of referring to a dermatologist, with the inherent delays and costs, AI also could save the patient from the innate stress of waiting for the appointment. This represents a significant potential gain in the value of point-of-care testing.48 Furthermore, it has moved care from the office to the home. In this particular study, Google AI was trained on a dataset of 129,540 images, which is about 10 times the lifetime experience of a typical dermatologist. The current projected number of smartphones worldwide is 1.16 billion. For the United States, the projected number is 364 million devices by 2040, making them a potential low-cost universal healthcare solution.49

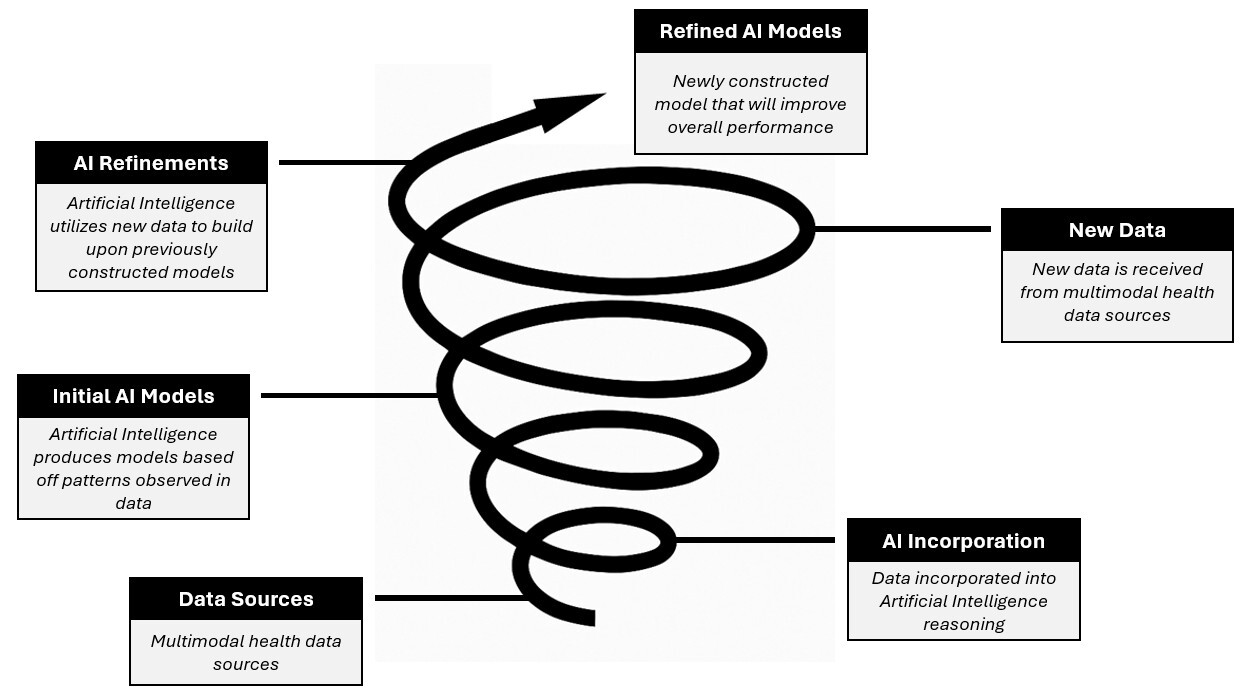

To truly harness the potential of AI to study large datasets, there would be a need to allow it to accrue more data (perhaps in real-time), re-analyze it, and constantly update its prediction formulas. An even grander scheme would be to integrate all data from large systems (i.e., all EPIC users or all the hospitals in the same system) to build massive datasets for AI to use in a continuous feed-forward loop (see Figure 1). A study that already has used this approach used ML to automatically evaluate and continuously update pre-operative risk assessments.50 The AI program, at the time of publication, was using a 37 million patient dataset with 194 clinical variables. How much better could AI perform if given access to even larger datasets? How much better could medical care be if we were constantly upgrading our assessment tools? This obviously raises significant privacy concerns, which will be discussed in the “Threats” section.

Figure 1. Feed-Forward Loop of AI and Refinement in Medicine |

|

AI: artificial intelligence |

True Precision Medicine

The promise of truly personalized and precision medicine has yet to be realized, even though the Human Genome Project completed sequencing in 2001.51,52 AI is ideal for handling and evaluating the large amount of data required to realize this goal.

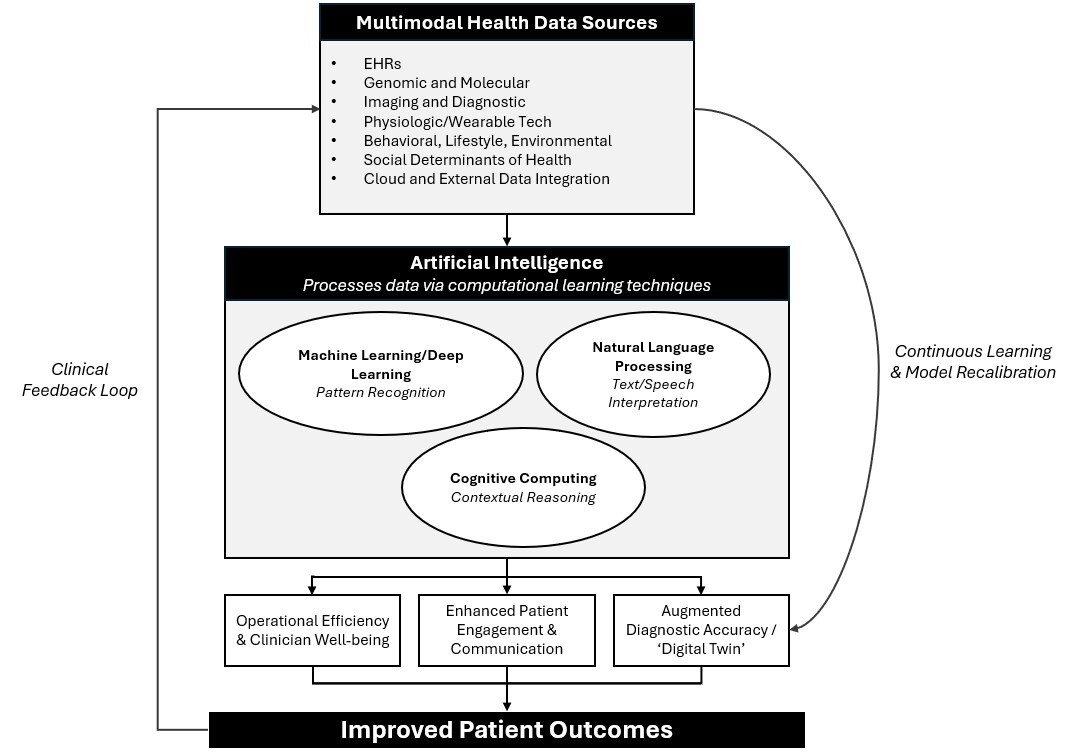

Genetic information will be evaluated alongside laboratory work, imaging, medication, wearable device data, social media posts, and lifestyle habits to arrive at not only a personalized risk assessment, but also a personalized model for each individual patient’s response to various treatments. This concept is called a “digital twin.”53,54 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2. Artificial Intelligence and Medicine |

|

Artificial intelligence (AI) synthesizes health data, including electronic health records (EHRs), genomics, imaging, physiologic sensors, behavioral and lifestyle factors, and social determinants, into clinically actionable insights. Using machine and deep learning, natural language processing, and cognitive computing, AI enhances operational efficiency, clinician well-being, patient engagement, and diagnostic accuracy, leading to improved outcomes. |

A digital twin is a virtual simulation of an individual that encompasses all known biomedical information pertaining to them. AI can use these models by running simulations on how the individual would respond to various therapies in isolation, as well as in combination. Instead of a purely empirical, cookie-cutter approach to therapy, the doctor and patient could discuss the probabilities of success and the risks of complications in a very objective and personalized way.

One of the largest practical areas of quality improvement would be to combine several technologies: AI, virtual reality (VR), and robotic surgery. What if surgeons and proceduralists could practice complex surgeries multiple times before performing the operation on the patient? Using three-dimensional imaging, AI, and VR, this could be done. Physicians performing complex procedures, such as tumor resection or brain surgery, largely could benefit from access to simulations that would allow them to practice, reducing complications and leading to a higher likelihood of success. Finally, AI could offer real-time advice during cases, calling on a large volume of applicable data. Ultimately, the final decision would be in the hands of the physician and depend on their own skill level and experience.

Threats

While popularized in numerous movies, such as War Games, The Terminator, and the Matrix series, an AI-induced global nuclear apocalypse is beyond the scope of this review. However, there are significant threats, or at least disruptions that AI may cause.

AI Will Take Our Jobs

This is unlikely. The same investigators studying smart camera usage in skin cancer detection expect a significant increase in dermatology visits.48 Although many patients will be relieved that AI does not determine that they have skin cancer, the increased volume of AI photo assessments most likely will flag cases that typically would never be diagnosed in the past because of access. These patients will need to see a dermatologist. Similarly, there will be a parallel increase between testing and the need to evaluate said new abnormal results.

AI Will Erode Trust Between Patient and Physician

While many are excited about the potential of AI, many do not trust it. A 2022 survey of 11,004 patients conducted by the Pew Research Center found that 60% of Americans were “uncomfortable” with their doctor using AI to help diagnose or recommend treatments.55 A more technical question also is important to consider: the so-called black box problem.

AI is a broad term that encompasses many different types of predictive modeling. One important distinction is deep learning and ML. ML generally is more accepted, since we can see exactly which variables were used and to what degree they were weighted to produce the risk score or prediction. This is similar to multivariate analysis, but each variable is weighted differently and compared with other variables, which also are adjusted in multiple iterative steps until the optimal outcome is derived.

Deep learning arrives at a conclusion but does not explain how the particular result was produced. This is called the black box problem, which ultimately is an issue of trust. Most people, especially doctors and patients, are not willing to give up final decision-making authority without understanding how that decision was made. For a more detailed discussion of the explainability of AI models, please see the Viewpoint by Ghassemi et al in The Lancet Digital Health.56

AI Opens Pandora’s Box of Serious Cybersecurity Risks

Giving AI access to large datasets that combine clinical, personal, and financial information puts greater strain on security. The most recent peer-reviewed publication on this topic, published in 2022, presented sobering statistics.57 Ninety percent of hospitals and offices already have experienced a data breach. The rate of healthcare attacks has tripled in the last decade. Each breach was associated with a cost of 7.13 million dollars.57

Beyond the cost, a cyberattack can escalate from a data breach to a direct threat on patient care if, for example, it prevents a hospital or office from delivering or monitoring care. The more access we give AI, the more vulnerabilities we will need to protect.

AI Will Lead to a Worse Physician Work Environment

A recent prospective piece discussed the potential problems of AI surveillance and becoming “quantified” factory-type workers.58 AI easily could be used to monitor and then grade your time use, efficiency, and empathy, as well as time use on your computer (work vs. shopping on Amazon or being on social media). These new metrics then could be used to help decide promotion, compensation, or both. AI also could be used to detect conversations (text, chat, email, verbal) that go against hospital policy.

AI could become “mechanical managers.” This already has been piloted in warehouses and in the financial sector. Examples include, but are not limited to, location tracking, keystroke logging, and intermittent screenshot capture without the subject’s consent. This implementation has led to worsening job satisfaction.59 AI functioning in this manner resembles the surveillance state, akin to Big Brother in the novel 1984.

AI Will Reduce Quality

Although this seems counterintuitive, it has most recently been brought up in the area with the most AI involvement: AI ambient listening and dictation. As we accrue larger and larger AI-dictated datasets, which reuse the same words and phrases, there is a higher likelihood of AI choosing these same phrases repeatedly. This cyclical back-referencing undoubtedly will limit the breadth, nuance, and context of dictations produced by LLMs.60 A danger that this loss of subtlety presents is a weaker patient-doctor relationship as the result of important aspects of the conversation being overlooked.

AI Will Lead to Skill Erosion

Another emerging threat is the potential erosion of core clinical skills with widespread AI use. The incorporation of AI into the clinical space has the potential to shift a physician’s hands-on decision-making to a role of overseeing generated recommendations.61 The results of a systematic review conducted by Natali et al revealed 17 areas of skill erosion that may arise because of AI. Several of these concerns align with the earlier sections.61

Among the domains identified were reduced practice with diagnostic reasoning, diminished proficiency in clinical documentation, decreased familiarity with physical examination skills, and overreliance on automated triage and decision-support systems. Natali et al also highlighted risks to communication skills, situational awareness, and independent data interpretation — competencies that form the backbone of clinical training.61 These concerns are especially relevant for medical trainees who still are developing foundational decision-making habits and may be more prone to deferring to algorithmic output rather than cultivating their own judgment.

Looking Into the Future …

Any predictions about the future of AI are inherently uncertain because of the rapid pace of change in this field. As soon as the reader completes this review, a significant portion most likely will be outdated.

What we do know is that AI already is making an impact on how medical professionals deliver care and will continue to do so. Knowing this, clinicians will need to become comfortable interacting with AI and leveraging its advantages, all the while understanding its shortcomings.

How we work with AI is the real question. There are two described ways: being a centaur or a cyborg.17

Like the mythical centaur, some will have divided areas of medicine in which they will employ AI and some where they will not. The other, and more likely, best model is the cyborg, where AI is integrated into all aspects of medical care. Regardless of which model we choose, there will be a learning curve, and it will require the adaptation of new habits. With the current trajectory of AI development, there is not a future where we completely ignore its application.

AI will not replace us but will assist us soon at the point of patient care and even further upstream in the patients’ homes. This innovative technology will help us to engage more deeply with our patients, reduce cognitive load and burnout, and increase enjoyment in our work. While pop culture often paints AI as a harbinger of doom, its true potential lies in revolutionizing and saving the medical field.

Maxwell C. Shull, Kettering Medical Center, Kettering, OH

Harvey S. Hahn, MD, Program Director, Cardiovascular Fellowship Training Program, Kettering Medical Center, Kettering, OH

References

1. Cabral BP, Braga LAM, Conte Filho CG, et al. Future use of AI in diagnostic medicine: 2-wave cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2025;27:e53892.

2. Puyt RW, Lie FB, Wilderom CPM. The origins of SWOT analysis. Long Range Plann. 2023;56(3):102304.

3. Rai B, Gilbert Z, Croughan CB, Hahn HS. The Hippocratic oath: Are we hurting ourselves and each other? Prim Care Rep. 2023;29(5):49-59.

4. American Medical Informatics Association. AMIA survey underscores impact of excessive documentation burden. Published June 3, 2024. https://amia.org/news-publications/amia-survey-underscores-impact-excessive-documentation-burden

5. Duggan MJ, Gervase J, Schoenbaum A, et al. Clinician experiences with ambient scribe technology to assist with documentation burden and efficiency. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(2):e2460637.

6. Nelson K, Stewart G. Primary care transformation and physician burnout. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(1):7-8.

7. Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper and Row; 1990.

8. American Medical Informatics Association. AMIA 25x5: Reducing documentation burden to 25% of current state in five years. https://amia.org/about-amia/amia-25x5

9. You JG, Dbouk RH, Landman A, et al. Ambient documentation technology in clinician experience of documentation burden and burnout. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(8):e2528056.

10. Medical Group Management Association. Ambient AI solution adoption in medical practices. https://www.mgma.com/getkaiasset/b02169d1-f366-4161-b4d6-551f28aad2c9/NextGen-AmbientAI-Whitepaper-2024-final.pdf

11. Small WR, Wiesenfeld B, Brandfield-Harvey B, et al. Large language model-based responses to patients’ in-basket messages. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(7):e2422399.

12. Kong M, Fernandez A, Bains J, et al. Evaluation of the accuracy and safety of machine translation of patient-specific discharge instructions: A comparative analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2025; Jul 9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2024-018384. [Online ahead of print].

13. Apple Support. Translate in-person conversations with AirPods. https://support.apple.com/guide/airpods/translate-in-person-conversations-dev9c215ca94/web

14. Zaretsky J, Kim JM, Baskharoun S, et al. Generative artificial intelligence to transform inpatient discharge summaries to patient-friendly language and format. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(3):e240357.

15. Dell Acqua F, McFowland E III, Mollick ER, et al. Navigating the jagged technological frontier: Field experimental evidence of the effects of AI on knowledge worker productivity and quality. Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Management Unit Working Paper No. 24-013. Revised Sept. 27, 2023. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4573321

16. Landi H. OpenEvidence AI scores 100% on USMLE as company launches explanation model for medical students. Fierce Healthcare. Published August 15, 2025. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/ai-and-machine-learning/openevidence-ai-scores-100-usmle-company-offers-free-explanation-model

17. Bradbury NA. Attention span during lectures: 8 seconds, 10 minutes, or more? Adv Physiol Educ. 2016;40(4):509-513.

18. Wrzeszczynski KO, Frank MO, Koyama T, et al. Comparing sequencing assays and human-machine analyses in actionable genomics for glioblastoma. Neurol Genet. 2017;3(4):e164.

19. Nori H, Daswani M, Kelly C, et al. Sequential diagnosis with language models. arXiv. Revised July 2, 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.22405

20. Shmatko A, Jung AW, Gaurav K, et al. Learning the natural history of human disease with generative transformers. Nature. 2025;647(8088):248-256.

21. Hager P, Jungmann F, Holland R, et al. Evaluation and mitigation of the limitations of large language models in clinical decision-making. Nat Med. 2024;30(9):2613-2622.

22. Steele AJ, Denaxas SC, Shah AD, et al. Machine learning models in electronic health records can outperform conventional survival models for predicting patient mortality in coronary artery disease. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202344.

23. Samad M, Ulloa A, Wehner G, et al. Predicting survival from large echocardiography and electronic health record datasets: Optimization with machine learning. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(4):681-689.

24. Kahneman D. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2013.

25. Daniel Kahneman — Facts. NobelPrize.org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2002/kahneman/facts/

26. Singer DE, Chang Y, Fang MC, et al. The net clinical benefit of warfarin anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(5):297-305.

27. Duy Mai T, Ho THQ, Hoang SV, et al. Comparative analysis of the net clinical benefit of direct oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: Systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur Cardiol. 2025;20:e13.

28. Van Ganse E, Danchin N, Mah I, et al. Comparative safety and effectiveness of oral anticoagulants in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: The NAXOS study. Stroke. 2020;51(7):2066-2075.

29. Banerjee A, Lane DA, Torp-Pedersen C, Lip GYH. Net clinical benefit of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus no treatment in a real world atrial fibrillation population: A modelling analysis based on a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(3):584-589.

30. Fischer KB, Valencia DN, Reddy A, et al. Effects of artificial intelligence clinical decision support tools on complications following percutaneous coronary intervention. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2025;4(3 Part B):102497.

31. LeLorier J, Gregoire G, Benhaddad A, et al. Discrepancies between meta-analyses and subsequent large randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(8):536-542.

32. Miley J. Scientists create world’s first “psychopath” AI by making it read Reddit captions. Interesting Engineering. Published June 8, 2018. https://interestingengineering.com/innovation/scientists-create-worlds-first-psychopath-ai-by-making-it-read-reddit-captions

33. Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in plain sight — Reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):874-882.

34. Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. The race-correction debates — Progress, tensions, and future directions. N Engl J Med. 2025;393(10):1029-1036.

35. Bracic A, Callier SL, Price WN 2nd. Exclusion cycles: Reinforcing disparities in medicine. Science. 2022;377(6611):1158-1160.

36. Dastin J. Insight — Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Reuters. Published Oct. 10, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/insight-amazon-scraps-secret-ai-recruiting-tool-that-showed-bias-against-women-idUSKCN1MK0AG/

37. Gustin S. Watson supercomputer terminates humans in first Jeopardy round. Wired. Published Feb. 15, 2011. https://www.wired.com/2011/02/watson-game-one/

38. Kalai AT, Nachum O, Vempala S, Zhang E. Why language models hallucinate. OpenAI. Published Sept. 4, 2025. https://cdn.openai.com/pdf/d04913be-3f6f-4d2b-b283-ff432ef4aaa5/why-language-models-hallucinate.pdf

39. Abdulnour RE, Gin B, Boscardin CK. Educational strategies for clinical supervision of artificial intelligence use. N Engl J Med. 2025;393(8):786-797.

40. Meta. AI glasses for effortless connection. https://www.meta.com/ai-glasses/

41. Meta. See more — without ever looking away. https://www.meta.com/ai-glasses/meta-ray-ban-display/

42. Gandhi TK, Classen D, Sinsky CA, et al. How can artificial intelligence decrease cognitive and work burden for front line practitioners? JAMIA Open. 2023;6(3):ooad079.

43. Abdelgadir Y, Thongprayoon C, Miao J, et al. AI integration in nephrology: Evaluating ChatGPT for accurate ICD-10 documentation and coding. Front Artif Intell. 2024;7:1457586.

44. Van Veen D, Van Uden C, Blankemeier L, et al. Adapted large language models can outperform medical experts in clinical text summarization. Nat Med. 2024;30(4):1134-1142.

45. Bhuyan SS, Sateesh V, Mukul N, et al. Generative artificial intelligence use in healthcare: Opportunities for clinical excellence and administrative efficiency. J Med Syst. 2025;49(1):10.

46. Mohamed A, Elsherif S, Legere B, et al. Is telestroke more effective than conventional treatment for acute ischemic stroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Stroke. 2024;19(3):280-292.

47. Mori Y, Kudo SE, Misawa M, et al. Real-time use of artificial intelligence in identification of diminutive polyps during colonoscopy: A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(6):357-366.

48. Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa R, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542(7639):115-118.

49. Consumer Affairs Journal of Consumer Research. Cell phone statistics 2025. Consumer Affairs. Updated March 20, 2025. https://www.consumeraffairs.com/cell_phones/cell-phone-statistics.html

50. Corey KM, Kashyap S, Lorenzi E, et al. Development and validation of machine learning models to identify high-risk surgical patients using automatically curated electronic health record data (Pythia): A restrospective, single-site study. PLoS Med. 2018;15(11):e1002701.

51. Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, et al; International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409(6822):860-921.

52. Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291(5507):1304-1351.

53. Vallee A. Digital twin for healthcare systems. Front Digit Health. 2023;5:1253050.

54. Sun T, He X, Li Z. Digital twin in healthcare: Recent updates and challenges. Digit Health. 2023;9:20552076221149651.

55. Tyson A, Pasquini G, Spencer A, Funk C. 60% of Americans would be uncomfortable with provider relying on AI in their own health care. Pew Research Center. Published Feb. 22, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2023/02/22/60-of-americans-would-be-uncomfortable-with-provider-relying-on-ai-in-their-own-health-care/

56. Ghassemi M, Oakden-Rayner L, Beam AL. The false hope of current approaches to explainable artificial intelligence in health care. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(11):e745-e750.

57. Wasserman L, Wasserman Y. Hospital cybersecurity risks and gaps: Review (for the non-cyber professional). Front Digit Health. 2022;4:862221.

58. Cohen IG, Ajunwa I, Parikh RB. Medical AI and clinical surveillance — the risk of becoming quantified workers. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(23):2289-2291.

59. Ajunwa I. The Quantified Worker: Law and Technology in the Modern Workplace. Cambridge University Press; 2023.

60. McCoy LG, Manrai AK, Rodman A. Large language models and the degradation of the medical record. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(17):1561-1564.

61. Natali C, Marconi L, Dias Duran LD, Cabitza F. AI-induced deskilling in medicine: A mixed-method review and research agenda for healthcare and beyond. Artif Intell Rev. 2025;58(356):1-40.