Obtaining Pediatric Vascular Access

December 1, 2025

Executive Summary

- Common insertion sites vary with age and developmental stage. In neonates and infants, accessible options include the scalp veins (particularly temporal and frontal branches), the dorsal veins of the hands and feet, and the great saphenous vein at the medial aspect of the ankle. In toddlers and older children, preferred sites include the dorsum of the hand, the forearm veins, and the antecubital fossa, with site selection guided by vein visibility, ease of cannulation, and the anticipated duration of intravenous (IV) line therapy.

- Ultrasound-guided peripheral intravenous (USGPIV) access has become an increasingly valuable tool in pediatric vascular access, especially in patients with difficult intravenous access (DIVA), such as those with obesity, chronic illness, or poor peripheral vein visibility. The use of real-time ultrasound enhances visualization of deeper or poorly visible veins, allowing for higher success rates and fewer cannulation attempts compared to traditional landmark-based approaches.

- While near-infrared (NIR) vein visualization devices also attempt to improve peripheral IV access by projecting subcutaneous vasculature onto the skin surface, their effectiveness in pediatric patients has shown mixed results. A study by Cuper et al compared NIR to USGPIV in a pediatric emergency department and found no improvement in first-attempt success rates with NIR (52%) compared to traditional methods (54%), whereas ultrasound showed significant benefit (83% success on first attempt). NIR is limited by its inability to visualize deeper veins and lacks real-time needle guidance, which may reduce its effectiveness in challenging cases.

- Despite its benefits, USGPIV access is not without limitations. It is more time-consuming in some cases, especially for novice operators, and requires specialized equipment not always available in resource-limited or prehospital settings. However, as training becomes more widespread and equipment more portable, USGPIV is increasingly considered the standard of care for pediatric patients with difficult IV access, and its use is endorsed by clinical guidelines and pediatric emergency care protocols.

- IO access is a critical method of vascular access used when IV access is not feasible, particularly in emergency and resuscitative settings. It provides a rapid, reliable route for the administration of fluids, medications, and blood products. The intraosseous (IO) space contains a rich network of venous sinusoids that drain directly into the central circulation, allowing for systemic drug delivery equivalent to IV access in terms of onset and plasma concentration. Preferred insertion sites vary based on patient age because of anatomical differences in bone size, cortex thickness, and accessibility. In neonates and infants, the proximal tibia most commonly is used, approximately 1 cm to 2 cm below the tibial tuberosity on the anteromedial surface. In older infants and toddlers, the distal femur also is a viable alternative. In older children and adolescents, both the proximal humerus and distal tibia may be used, depending on accessibility and clinical scenario.

Vascular access is a cornerstone of effective pediatric emergency care and essential for resuscitation of critically ill or injured children. This review provides a comprehensive overview of pediatric vascular access strategies in the emergency department, emphasizing evidence-based methods and practical techniques to improve success rates and minimize complications.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, FAAP, FACEP, Editor

By Kelli A. Wells, MD, MPH; Kiefer Kious, MD, MS; and Daniel Migliaccio, MD, FPD, FAAEM

Introduction

Timely vascular access is a cornerstone of effective pediatric emergency care, enabling the rapid administration of life-saving medications, fluids, and blood products. In critically ill or injured children, delays in establishing access can significantly affect outcomes, particularly in conditions such as septic shock, status epilepticus, or traumatic injury.1,2 However, achieving vascular access in pediatric patients presents unique challenges not typically encountered in adults. Smaller blood vessel size, increased subcutaneous fat, variable anatomy, and limited patient cooperation — especially in infants and young children — can make even routine access technically difficult.3

Emotional stress among caregivers and providers during emergencies further complicates the process. Therefore, emergency physicians must be proficient in a range of access techniques tailored to the child’s age, size, and clinical condition. These include traditional peripheral intravenous lines (IVs), ultrasound-guided peripheral and central access, intraosseous (IO) access for rapid resuscitation, umbilical venous catheterization in neonates, and alternative sites, such as scalp and saphenous veins.4-6 Recent studies have demonstrated the increasing safety and success rates of ultrasound-guided and IO access in pediatric patients, even in prehospital and critical care transport settings.7,8 This review provides a comprehensive overview of pediatric vascular access strategies in the emergency department, emphasizing evidence-based methods and practical techniques to improve success rates and minimize complications.

Background

Establishing vascular access in pediatric patients presents unique challenges compared to adults because of key anatomical and physiological differences, behavioral factors, and clinical considerations. Children have smaller, more fragile veins, increased subcutaneous fat, and lower circulating blood volume, which heighten the risk of rapid hemodynamic decompensation in emergencies. Furthermore, pediatric patients may not cooperate during procedures because of fear, their developmental stage, or pain, necessitating the use of age-appropriate distraction techniques or pharmacologic sedation, such as intranasal midazolam or intramuscular ketamine. The selection of vascular access — peripheral intravenous (PIV), IO, central venous catheter (CVC), or ultrasound-guided options — should be based on the urgency of the situation, anticipated duration of therapy, and the patient’s clinical condition. For instance, IO access often is preferred during critical resuscitations when rapid IV access is not feasible, while central lines may be indicated for long-term therapy or administration of vasoactive agents. To improve success rates and minimize trauma, practitioners should use appropriately sized equipment, employ vein visualization tools (transillumination or ultrasound), and ensure proper positioning and immobilization techniques. Structured training and simulation-based practice also can enhance proficiency and reduce complications.

Table 1 outlines the key differences between adult and pediatric patient anatomy relevant to vascular access.

Table 1. Comparison of Pediatric vs. Adult Vascular Anatomy for Vascular Access |

Vein Size

|

Vein Depth

|

Vein Wall Thickness

|

Subcutaneous Fat

|

Common Peripheral Sites

|

Intraosseous Sites

|

Ultrasound Usefulness

|

First-Attempt Success Rate

|

Peripheral Intravenous Access

PIV access remains the most frequently employed method for vascular access in pediatric emergency settings because of its relative ease, rapidity, and noninvasive nature. However, this technique poses significant challenges in children, driven by smaller vessel size, increased subcutaneous fat, and limited cooperation during procedures.9

Common insertion sites vary with age and developmental stage. In neonates and infants, accessible options include the scalp veins (particularly temporal and frontal branches), the dorsal veins of the hands and feet, and the great saphenous vein at the medial aspect of the ankle. In toddlers and older children, preferred sites include the dorsum of the hand, the forearm veins, and the antecubital fossa, with site selection guided by vein visibility, ease of cannulation, and the anticipated duration of IV therapy.10

When time permits, topical anesthetics can significantly reduce pain and distress related to venipuncture. Anesthetics, such as lidocaine-prilocaine cream (EMLA) and liposomal lidocaine 4% (LMX-4), commonly are used in pediatric patients and can significantly reduce pain and anxiety that often is associated with venipuncture in children. Both agents are applied in a 1-g to 2-g layer over the intended site and covered with an occlusive dressing for approximately 30-60 minutes prior to trying needle insertion. Vapocoolant sprays (ethyl chloride) or instant cold sprays provide near-instant superficial anesthesia and can be used with minimal delay when quick access is required.11-13

Vein dilation strategies routinely are employed to improve the likelihood of successful cannulation. These include the application of warm compresses to promote vasodilation, tourniquets to engorge peripheral veins, and transillumination or near-infrared (NIR) devices to enhance subcutaneous vein visualization. Although NIR devices have demonstrated improved first-attempt success in pediatric patients with difficult intravenous access (DIVA), their utility in all clinical scenarios remains mixed.11

NIR vein visualization devices have emerged as valuable tools for enhancing the success of peripheral intravenous placement in pediatric patients, particularly those with DIVA. These devices use infrared light to detect hemoglobin-rich vasculature beneath the skin and project a real-time image of subcutaneous veins onto the skin surface. Studies have shown that NIR devices can improve first-attempt success rates and reduce the number of cannulation attempts specifically in children with low vein visibility or a history of failed attempts, although there was no improvement in the general pediatric population.14,15 However, despite these benefits, limitations remain. The effectiveness of NIR devices decreases in patients with darker skin tones, in settings with high ambient light, or in patients with excessive subcutaneous fat, which can obscure vein visualization.16 Additionally, operator inexperience with interpreting the NIR image can negate potential benefits.17 The devices also lack depth perception, making them less effective than ultrasound in cases where veins are not superficial. Thus, while NIR technology serves as a helpful adjunct, it should be viewed as a complementary tool rather than a universal solution, with careful attention to patient-specific factors and operator training.

Figure 1 demonstrates a handheld infrared vein finder in use.

Figure 1. Handheld Infrared Vein Finder |

|

Courtesy of Kiefer Kious, MD, MS |

Ultrasound-Guided PIV Access

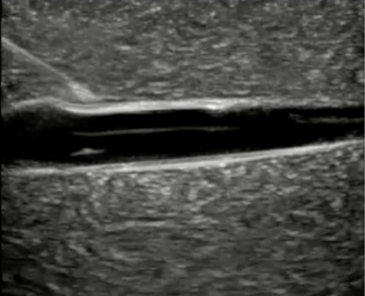

Ultrasound-guided peripheral intravenous (USGPIV) access has become an increasingly valuable tool in pediatric vascular access, especially in patients with DIVA, such as those with obesity, chronic illness, or poor peripheral vein visibility. The use of real-time ultrasound enhances visualization of deeper or poorly visible veins, allowing for higher success rates and fewer cannulation attempts compared to traditional landmark-based approaches. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2. Long Axis Approach of a Catheter into a Vessel |

|

Courtesy of Daniel Migliaccio, MD |

Multiple studies have demonstrated the clinical efficacy of USGPIV in pediatric patients. A randomized controlled trial by Doniger et al compared USGPIV with conventional techniques in children aged 0-21 years presenting to the emergency department with DIVA. The study found a significantly higher first-attempt success rate with ultrasound guidance (85% vs. 45%) and a shorter time to successful cannulation.18 Similarly, a meta-analysis by Heinrichs et al, which included more than 1,000 pediatric patients, found that ultrasound guidance significantly improved the likelihood of first-attempt success (odds ratio 2.64; 95% confidence interval, 1.43-4.88) and reduced the number of attempts and procedure duration.19

Ultrasound is particularly beneficial in identifying and cannulating deeper veins, such as the basilic or brachial veins, which are not accessible by visual inspection or NIR devices. In the prospective cohort study titled the DIAPEDUS Study of children with DIVA (defined by a DIVA score ≥ 4 or prior difficult access), ultrasound-assisted IV access achieved a first-attempt success rate of 90% vs. 18% in the standard technique group, and the overall success rate also was higher (95% vs. 46%).20 This advantage is most notable in settings where repeated failed attempts can delay care or necessitate escalation to more invasive procedures, such as IO or central venous access.

While NIR vein visualization devices also attempt to improve peripheral IV access by projecting subcutaneous vasculature onto the skin surface, their effectiveness in pediatric patients has shown mixed results. A study by Cuper et al compared NIR to USGPIV in a pediatric emergency department and found no improvement in first-attempt success rates with NIR (52%) compared to traditional methods (54%), whereas ultrasound showed significant benefit (83% success on first attempt).21 NIR is limited by its inability to visualize deeper veins and lacks real-time needle guidance, which may reduce its effectiveness in challenging cases.

Ultrasound-guided techniques require operator training and experience to achieve optimal outcomes. Skill development includes familiarity with high-frequency linear probes (10 MHz to 15 MHz), dynamic needle tip visualization, and hands-free techniques using vein stabilization. Real-time ultrasound guidance also enables detection of complications such as infiltration or misplacement during catheter advancement, increasing overall procedural safety.

Despite its benefits, USGPIV access is not without limitations. It is more time-consuming in some cases, especially for novice operators, and requires specialized equipment not always available in resource-limited or prehospital settings. However, as training becomes more widespread and equipment more portable, USGPIV is increasingly considered the standard of care for pediatric patients with difficult IV access, and its use is endorsed by clinical guidelines and pediatric emergency care protocols.22

PIV-related complications include hematoma formation from multiple failed attempts, infiltration and extravasation of infusions (especially concerning with vesicant medications), phlebitis caused by mechanical or chemical irritation, and infection from breaches in aseptic technique.22 Proper technique, vigilant monitoring, and prompt intervention at signs of complication are critical in minimizing adverse outcomes. Adherence to best practices — such as meticulous site selection, aseptic insertion protocols, appropriate catheter sizing, and regular reassessment — enhances both procedural success and patient safety.

Scalp Vein Access

Scalp vein cannulation is a valuable technique for achieving PIV access in neonates and young infants, particularly those younger than 6 months of age, when extremity veins are not easily visualized or cannulated. Scalp veins are superficial and relatively immobile, making them less prone to collapse compared to other peripheral veins in this age group, even in hemodynamically compromised patients. Commonly used veins include the superficial temporal vein, posterior auricular vein, and frontal scalp veins, which can be identified visually or by gentle palpation.23 Transillumination and NIR devices may aid visualization in difficult cases.

Typically, a 22- or 24-gauge IV catheter is used depending on vein size and patient age. Proper positioning, often with the infant supine and the head slightly turned, combined with immobilization using soft restraints or caregiver assistance, is essential for successful cannulation and to reduce the risk of dislodgement.24 Dressings should be transparent and well-secured to allow continuous inspection and reduce the risk of inadvertent removal.

Scalp veins generally are suitable only for short-term access — typically less than 24 to 48 hours — because of the increased risk of dislodgement, infiltration, and infection. There also are important limitations regarding the medications and infusion rates that can be safely administered through these veins. Vesicant drugs, hyperosmolar solutions, and agents with high or low pH (e.g., parenteral nutrition, certain antibiotics, chemotherapy) should be avoided because of the risk of extravasation and tissue injury.24,25 High-pressure or rapid infusions are similarly discouraged. If an infusion pump is used, it should include pressure monitoring and alarms to detect early signs of infiltration.23

Cosmetic concerns, such as potential scarring or alopecia, generally are minimal when proper technique is followed, but these risks contribute to recommendations that scalp access be reserved for situations where extremity access is not feasible. When used appropriately, scalp vein IV access offers a reliable and effective route for medication and fluid administration in infants, especially in emergency or critical care settings.

Saphenous Vein Access

The saphenous vein, particularly the great saphenous vein at the medial ankle, is a reliable and frequently used site for PIV access in neonates and young children. This vein lies anterior to the medial malleolus and often is visible or palpable in infants because of their thin skin and low subcutaneous fat. In older children, increased adiposity and deeper vessel location may reduce its visibility, although the site remains accessible in children younger than 3 years of age.26

In emergency settings, the great saphenous vein at the ankle is favored for its predictable anatomical location, relative ease of immobilization, and low complication rate. The small saphenous vein, located posterior to the lateral malleolus, also may be used, although its variable anatomy makes it less commonly selected. For neonates and infants, 22- or 24-gauge IV catheters generally are appropriate. Proper positioning, such as externally rotating and slightly dorsiflexing the foot, along with vein dilation techniques (warm compresses or limb lowering) can enhance cannulation success.

Ultrasound guidance has been shown to improve first-attempt success rates and is particularly helpful in patients with DIVA or increased subcutaneous tissue.27 A high-frequency linear probe (10 MHz to 15 MHz) allows real-time visualization of the vein, catheter entry, and confirmation of placement. However, ultrasound requires operator skill and may not be available in all clinical settings.

Saphenous access is suitable for short- to intermediate-term IV therapy but generally is not appropriate for vesicant drugs, hyperosmolar infusions, or parenteral nutrition because of the risks of infiltration and tissue damage.24 Complications such as dislodgement, thrombophlebitis, and infection are rare but can occur if proper technique is not followed. Securing the catheter and careful monitoring are essential, especially in active or restless patients.

Although not a primary site in older children and adolescents, the saphenous vein remains an important alternative for PIV access in infants and toddlers, particularly when upper extremity veins are inaccessible. Its anatomical distance from the airway and chest also makes it a favorable site during procedures involving the upper body.

Subcutaneous Fluid Administration (Hypodermoclysis)

Subcutaneous fluid administration, also known as hypodermoclysis, is an additional alternative for fluid resuscitation when IV access is difficult (or delayed) but rapid resuscitation is not required. Although less common, this method can be used under the right circumstances, particularly in mild to moderate dehydration in geriatric or pediatric patients. The most common anatomical sites consist of the anterolateral thigh, abdomen, upper back, or deltoid region, where adequate subcutaneous tissue allows safe dispersion of fluid. Once a site is chosen and appropriately sterilized, a 22- to 25-gauge butterfly or short catheter is inserted subcutaneously at a 30° to 45° angle. Then, it is secured and connected to isotonic solutions, such as normal saline or half-normal saline with 5% dextrose. Infusion rates range from 20 mL/hour to 80 mL/hour or 1 mL/min/site. Infants to children should not receive more than 200 mL per injection site. Additionally, some clinicians may use hyaluronidase to reduce edema, increase absorption rate, and minimize discomfort in the patient. Infants and children can receive up to 30 units of hyaluronidase per 200 mL of infusate.28

Contraindications include severe dehydration or shock, coagulopathy, local infection, generalized edema, or situations requiring rapid volume expansion. Complications are uncommon but include swelling, pain, cellulitis, or fluid leakage at the insertion site. When used appropriately, subcutaneous fluids offer a safe, minimally invasive, and effective bridge for hydration until definitive vascular access can be established.28,29

Intraosseous Access in Pediatric Patients

IO access is a critical method of vascular access used when IV access is not feasible, particularly in emergency and resuscitative settings. It provides a rapid, reliable route for the administration of fluids, medications, and blood products. The IO space contains a rich network of venous sinusoids that drain directly into the central circulation, allowing for systemic drug delivery equivalent to IV access in terms of onset and plasma concentration.30

Preferred insertion sites vary based on patient age because of anatomical differences in bone size, cortex thickness, and accessibility. In neonates and infants, the proximal tibia most commonly is used, approximately 1 cm to 2 cm below the tibial tuberosity on the anteromedial surface. In older infants and toddlers, the distal femur also is a viable alternative. In older children and adolescents, both the proximal humerus and distal tibia may be used, depending on accessibility and clinical scenario.31 The proximal humerus, with its proximity to the central circulation, has been associated with faster infusion rates and may be preferred in older pediatric patients, particularly in cardiac arrest scenarios.

The distal femur generally is avoided in older children and adolescents because of increasing ossification, thicker cortical bone, and the proximity of the distal femoral physis (growth plate), which becomes more prominent and vulnerable to injury with age. As the medullary cavity becomes narrower and less accessible because of skeletal maturation, successful cannulation becomes more technically challenging and carries greater risk for growth plate damage or periosteal injury.32 Additionally, the overlying soft tissue may increase in volume with age, making identification of landmarks and successful needle placement more difficult.

Conversely, the proximal humerus is not routinely used in infants or younger children because of incomplete ossification of the humeral head and the presence of a cartilaginous epiphyseal plate, which is difficult to palpate or visualize — even with imaging assistance. Improper needle placement risks damaging the growth plate or penetrating the glenohumeral joint. Furthermore, the angle and trajectory required to access the narrow medullary canal in this population can be technically demanding, increasing the risk of insertion failure or misplacement.31,32 For these reasons, humeral IO access typically is reserved for older children and adolescents with sufficient bony development.

The fibula is not recommended as an IO site in older children because of its narrow medullary cavity, thinner cortex, and close proximity to neurovascular structures, such as the peroneal nerve. These anatomical limitations increase the risk of misplacement, extravasation, and nerve injury, making the site unreliable and potentially unsafe.

IO access can be obtained using manual or powered devices (e.g., EZ-IO). Needle size typically is chosen based on patient weight and soft tissue depth:

- neonates and infants (< 3 kg): 15 mm (pink needle, EZ-IO);

- children (3 kg to 39 kg): 25 mm (blue needle);

- adolescents and larger children (> 40 kg or excessive soft tissue): 45 mm (yellow needle). Proper landmarking, technique, and confirmation of flow are essential to reduce complications.

Although generally safe and effective, IO access is not without risks. Potential complications include extravasation, compartment syndrome, fracture, growth plate injury (especially in young children), infection (e.g., osteomyelitis), and fat embolism. The risk of these complications increases with prolonged use; thus, IO lines are recommended only as a bridge to definitive IV or central access and ideally should be replaced within 24 hours.33

Another important limitation is the inability to obtain large infusion volumes rapidly, especially with manual infusion methods. The use of pressure bags or infusion pumps is recommended to maintain adequate flow rates. Additionally, certain medications (e.g., vasopressors, chemotherapeutics) may require caution or are not recommended via IO because of the risk of local tissue necrosis if extravasation occurs.

Despite these limitations, IO access remains a lifesaving technique, particularly in prehospital, trauma, and cardiac arrest settings. Its rapid establishment and high success rate make it an essential skill for pediatric emergency and critical care providers.

Central Venous Access

Central venous access in pediatric patients frequently is indicated for a range of clinical scenarios, including administration of vasoactive medications, total parenteral nutrition, chemotherapy, hemodynamic monitoring, and long-term venous access for patients with chronic illness.34 In emergency settings, central venous access may be required when PIV access is unobtainable or insufficient for the clinical needs of the patient.

Contraindications to central line placement include local infection at the proposed insertion site, uncorrected coagulopathy (especially in non-compressible sites), and known or suspected anatomic anomalies, such as vascular thrombosis or congenital vascular malformations. In these cases, alternative access sites or modalities, such as IO access, may be considered.

While many of the principles of central line placement are shared with adult patients, pediatric anatomy, physiology, and developmental considerations necessitate distinct approaches. Pediatric patients exhibit significant age-related anatomical variability, particularly in vein size, depth from the skin, and proximity to surrounding structures. In neonates and infants, vessels are smaller, more superficial, and more prone to collapse with pressure from the ultrasound probe. In older children and adolescents, larger vessel caliber and more defined landmarks allow for easier access but also may present challenges in terms of deeper vessel depth and patient cooperation. Consequently, the technique must be adapted based on the child’s size, with adjustments in probe pressure, positioning, and needle angle.35

Placement Site and Age Considerations

Site selection for CVC access in children is influenced by age, weight, and clinical context. Common sites include the internal jugular vein (IJ), subclavian vein (SC), and femoral vein. In neonates and infants, the femoral vein often is favored because of its ease of access and a lower risk of pneumothorax. However, infection risk is higher with femoral lines and should be considered in prolonged catheterization.36-38 The IJ vein is preferred in older children and adolescents because of its compressibility and ease of ultrasound guidance. SC access, while common in adults, is less frequently used in children because of the increased risk of pneumothorax and catheter malposition, although it still may be appropriate in specific cases with experienced operators.23,36,39

Catheter Size Selection Based on Age and Weight

Selecting the correct CVC size in pediatric patients is critical for ensuring adequate flow, minimizing complications, and avoiding mechanical or thrombotic failure. Catheter size selection primarily is guided by the child’s age, weight, and the anatomical site of insertion. Neonates weighing less than 5 kg typically require a 3-4 Fr single-lumen or double-lumen catheter, while children weighing 5-15 kg usually are best served by a 4-5 Fr double-lumen catheter. Older children and adolescents (> 20 kg) may require 5-7 Fr catheters, particularly in critical illness scenarios requiring rapid volume administration or multiple infusions.

To aid clinicians in emergency and time-sensitive environments, several tools exist for estimating patient size and guiding catheter selection. One widely used tool is the Broselow tape, a length-based, color-coded resuscitation aid that recommends catheter sizes, medication doses, and equipment based on patient height. However, recent studies have highlighted significant limitations in its use because of increasing rates of pediatric overweight and obesity, which may lead to underestimation of weight by more than 10% in up to one-third of pediatric patients.40,41 This discrepancy can result in inappropriate catheter selection or subtherapeutic medication dosing. Alternatives, such as the PAWPER XL tape and the Mercy Method, have demonstrated improved accuracy, especially in overweight and obese children.42 Ultimately, bedside ultrasound remains the most accurate method to guide catheter sizing by directly measuring vein diameter and ensuring that the catheter-to-vein ratio remains below 33%, a threshold shown to reduce thrombosis risk.43

Ultrasound-Guided Central Line Placement

Ultrasound guidance has become the standard of care for central venous access in children, reducing complication rates and increasing first-attempt success compared to landmark techniques. Real-time ultrasound visualization of vascular structures, particularly the internal jugular vein, improves outcomes and has become routine in most pediatric emergency and intensive care settings. It has been shown to significantly improve the safety and success of the procedure across all pediatric age groups.

High-frequency linear transducers (10 MHz to 15 MHz) generally are preferred for their superior resolution of superficial structures. Real-time guidance allows for continuous visualization of the needle tip during advancement into the vessel, reducing the risk of posterior wall puncture and arterial injury. The short-axis (transverse) view provides a cross-sectional image of the vessel and surrounding anatomy and is useful for identifying landmarks, while the long-axis (in-plane) approach allows for visualization of the entire needle path but requires greater technical skill. Some clinicians employ a dual-plane approach to enhance safety and accuracy.39

Following successful cannulation, confirmation of catheter placement is essential to avoid complications. While ultrasound visualization of guidewire passage into the vessel and right atrium can provide immediate confirmation, additional methods such as chest radiography (particularly for SC and IG access) and ECG-guided catheter tip placement may be used to confirm location and rule out complications such as pneumothorax or malposition.44

Emergent Femoral Venous Access

During critical pediatric resuscitations, obtaining rapid vascular access often can be the determining factor between stability and decline. In these situations, emergent femoral venous access using a long PIV catheter provides a practical and efficient bridge to a more durable central access.45,46 The femoral vein runs medial to the femoral artery just beneath the inguinal ligament and can be localized by palpation or with the aid of ultrasound. After first using strict sterile technique, a long 22- to 18-gauge PIV catheter (1.75 to 2.5 inches) is introduced at a 30° to 45° angle, approximately 1 cm to 2 cm below the inguinal ligament and slightly medial to the arterial pulse. Once venous flashback is visualized, the catheter is advanced and appropriately secured for immediate use.

This approach allows clinicians to administer fluids, blood products, and vasoactive medications in a timely manner — often without the delays associated with a surgical cutdown or formal central-line placement. As with any vascular access procedure, it carries risks, including accidental arterial puncture, hematoma, and catheter dislodgment, particularly in smaller children. The use of ultrasound guidance consistently has been shown to improve first-pass success and reduce complications of these procedures.47 Although this technique is a temporary measure and not suitable for long-term therapy, it provides an invaluable option when IO access is contraindicated or has failed, ensuring resuscitation and stabilization efforts in critically ill children can continue without minimal interruption.

Complications and Mitigation Strategies

Potential complications of central venous catheterization in children include arterial puncture, pneumothorax, hemothorax, catheter malposition, air embolism, and central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs). The risk of these complications is higher in small children and neonates because of their smaller vessel diameter and closer proximity of arteries and veins.48 The use of ultrasound guidance has been repeatedly shown to reduce these risks. A meta-analysis by Brass et al demonstrated a significant reduction in arterial puncture and catheter failure rates with ultrasound compared to landmark-based techniques.47

Strict aseptic technique, proper barrier precautions, and bundle-based protocols for central line insertion and maintenance have been shown to reduce CLABSIs in both pediatric intensive care units and general wards.49 Furthermore, appropriate training in ultrasound-guided vascular access is critical, since proficiency is directly linked to reduced complication rates and improved patient outcomes.

Umbilical Venous Catheterization

Umbilical venous catheterization (UVC) is a commonly performed procedure in neonatal intensive care settings, primarily indicated for rapid fluid resuscitation, medication administration, central venous pressure monitoring, and exchange transfusion in critically ill neonates. Emergency physicians who care for neonates, especially in delivery rooms or community hospitals without on-site neonatal intensive care, should be proficient in this life-saving procedure as part of neonatal advanced life support protocols. UVC provides direct access to the central circulation through the patent umbilical vein, making it an essential tool in the immediate postnatal management of premature or critically ill infants.

Timing and Anatomical Considerations

UVC is most effective when placed within the first few days of life, typically within seven to 14 days postpartum, while the umbilical vein remains patent.50 After this window, the umbilical stump begins to dry and fibrose, increasing the difficulty and risk of the procedure. Anatomically, the umbilical vein runs superiorly to the left portal vein and continues into the ductus venosus into the inferior vena cava (IVC), offering a direct route to the right atrium. The ideal catheter tip position is at the junction of the IVC and right atrium, above the diaphragm, to ensure accurate central access and minimize the risk of complications.

Equipment and Technique

A sterile field must be maintained throughout the procedure. The appropriate catheter size is chosen based on the infant’s weight: typically, a 3.5 Fr catheter for infants < 3.5 kg and a 5 French catheter for infants > 3.5 kg.51 Additional necessary equipment includes sterile drapes, scalpel or scissors, forceps, suture materials, and sterile saline for catheter flushing.

The umbilical cord and surrounding skin are prepared with an antiseptic solution. A tie is placed around the cord, and it is cut 1 cm to 2 cm from the skin to expose the vessels. The catheter is inserted through the umbilical vein, identified as the thin-walled vessel at the 12 o’clock position in the umbilical stump. Following gentle dilation and insertion, the catheter is advanced toward the IVC in the direction of the right shoulder, generally to a depth of 4 cm to 6 cm plus the birth weight in kilograms, although estimated depth should be confirmed with imaging.52 The optimal tip position is at the junction of the IVC and right atrium, typically between thoracic vertebrae T7-T9 on radiographic imaging. The estimated insertion length can be calculated using weight-based formulas (e.g., Shukla or Dunn) to minimize the risk of malposition. Catheter advancement should be smooth; resistance may indicate coiling in the portal circulation, malposition, or vascular anomaly.

Confirmation and Securing the Line

Correct positioning is critical. Traditionally, confirmation is achieved using anterior-posterior chest and abdominal radiography, identifying the catheter tip at or just above the level of the diaphragm. However, ultrasound guidance has emerged as an improved method for both real-time placement and post-placement verification, reducing malposition rates, radiation exposure, and procedure time.53 Point-of-care ultrasound can visualize the catheter in the IVC and ensure it is not in the liver, portal venous system, or right atrium, thereby improving procedural success and safety. After placement, the catheter must be carefully secured using suture or securement devices and covered with sterile dressings to reduce the risk of dislodgement or infection.

Complications

Potential complications of UVC placement include catheter malposition (e.g., in the portal vein, hepatic vein, or right atrium), vascular perforation, arrhythmias, infection, thrombosis, and hepatic injury. The risk of CLABSIs increases with longer catheter dwell time.54 Appropriate insertion technique, real-time ultrasound confirmation, and diligent post-placement care — including catheter maintenance bundles and daily reassessment of necessity — are essential for minimizing adverse events.

Venous Cutdown

When all conventional methods of vascular access — including percutaneous, IO, and ultrasound-guided — have been exhausted, the venous cutdown remains a reliable and occasionally life-saving option in pediatric patients. The great saphenous vein, located anterior to the medical malleolus, is the most-used site because of its consistent anatomy and relative accessibility, even in profound hypovolemic states. After sterile preparation, a small longitudinal incision is made approximately 1 cm superior and 1 cm anterior to the medial malleolus with a surgical blade (11 blade). Local anesthesia may be used, pending time and patient’s clinical status. Blunt dissection then is used with curved hemostats to minimize injury to vasculature and best expose and isolate the vein. The vessel then is carefully mobilized by circumferential dissection around the vessel and passing two small vessel loops or silk ties around the vessel. Gentle traction on the distal tie elevates the vein while the proximal tie is tightened to occlude venous flow and prevent blood loss. A venotomy is performed on the anterior surface of the vein with iris scissors. An appropriately sized catheter (typically 18-22 gauge or a 5/6 Fr feeding tube) is inserted and secured with the vessel loop. The incision is loosely closed and covered with sterile dressing.55

However, IO access largely has replaced the cutdown in modern pediatric resuscitations because of its speed and simplicity. Regardless, the cutdown still holds value in some cases. It is especially useful when IO access is contraindicated, such as in osteogenesis imperfecta, local infection, fractures, and when percutaneous techniques have failed.55 Complications include infection, venous thrombosis, nerve injury, and scarring, underscoring the importance of meticulous aseptic technique and gentle dissection. Although venous cutdown can be undeniably time-intensive, it remains an essential skill for pediatric emergency and surgical teams facing refractory access challenges, particularly in resource-limited or field conditions.56

Conclusion

One of the most persistent challenges in pediatric emergency and critical care settings remains obtaining reliable vascular access. The process can be daunting, even for experienced clinicians, since pediatric patients exhibit a combination of small, fragile veins, variable anatomy, and little tolerance for repeat attempts. These variables require fine technical skills but also calm, deliberate judgment and the ability to adapt in a critical setting. The approach to vascular access often is taken for granted but must be approached in a thoughtful and stepwise manner. This starts with the simplest, least invasive method and may be escalated only as needed.

In practice, PIV should be the first-line approach. When PIV cannot be obtained in a timely manner, IO access provides a dependable alternative that allows for rapid fluid and blood product administration, as well as emergency medications when time is limited. Modern adjuncts, such as ultrasound and near-infrared visualization devices, have been shown to dramatically improve first-attempt success rates, reduce associated trauma with repeated needle sticks, and should be encouraged in most settings if available. Table 2 summarizes recommended pediatric vascular access routes and technieus by patient age and weight.

Table 2. Recommended Pediatric Vascular Access by Age and Weight |

Neonate (0-28 Days)

|

Infant (1-12 Months)

|

Toddler (1–3 Years)

|

Preschool (3–5 Years)

|

School-Age (6-12 Years)

|

Adolescent (> 12 Years)

|

Central venous catheterization remains essential for patients who require long-term access or vasoactive medications. The growing use of ultrasound guidance has revolutionized CVC placement, making it safer and more predictable, in both adult and pediatric patients. However, in rare critical scenarios when both PIV and IO access fail, emergent alternatives, such as a femoral venous stick using a long peripheral catheter or a surgical venous cutdown, may be the only remaining option. Under the care of a prepared team, these last-resort techniques can restore access, stabilize the patient, and subsequently save a life.

Pediatric vascular access is an art as much as it is a science. These procedures call for precision, patience, and teamwork — skills that are honed through simulation, repetition, and continuous interdisciplinary collaboration. Mastery of pediatric vascular access through education and practice ensures not only technical competence but readiness to act decisively when our youngest and most vulnerable patients need us most.

Kelli A. Wells, MD, MPH, is Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellow, University of North Carolina Hospitals, Chapel Hill.

Kiefer W. Kious, MD, MS, is Emergency Medicine Resident, University of North Carolina Hospitals, Chapel Hill.

Daniel Migliaccio, MD, FPD, FAAEM, is Clinical Associate Professor, Director of Emergency Ultrasound, Ultrasound Fellowship Director, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

References

- Bouhamdan J, Polsinelli G, Akers KG, Paxton JH. A systematic review of complications from pediatric intraosseous cannulation. Medical Student Research Symposium. Published January 2021. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1086&context=som_srs

- Ting A, Smith K, Wilson CL, et al. Pre-hospital intraosseous use in children: Indications and success rate. Emerg Med Australas. 2022;34(1):120-121.

- Nakayama Y, Takeshita J, Nakajima Y, Shime N. Ultrasound-guided peripheral vascular catheterization in pediatric patients: A narrative review. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):592.

- Mitchell EO, Jones P, Snelling PJ. Ultrasound for pediatric peripheral intravenous catheter insertion: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2022;149(5):e2021055523.

- Yalçın G, Özdemir Balcı Ö, Başer A, Anıl M. Use of intraosseous access in the pediatric emergency department: A single center experience. J Dr Behcet Uz Child Hosp. 2024;14(3):175-180.

- Schindler E, Schears GJ, Hall SR, Yamamoto T. Ultrasound for vascular access in pediatric patients. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22(10):1002-1007.

- Garabon JJW, Gunz AC, Ali A, Lim R. EMS use and success rates of intraosseous infusion for pediatric resuscitations: A large regional health system experience. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2023;27(2):221-226.

- Joerck C, Wilkinson R, Angiti RR, et al. Use of intraosseous access in neonatal and pediatric retrieval — Neonatal and pediatric emergency transfer service, New South Wales. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2023;39(7):e1234-e1239.

- Larsen P, Eldridge D, Brinkley J, et al. Pediatric peripheral intravenous access: Does nursing experience and competence really make a difference? J Infus Nurs. 2010;33(4):226-235.

- Naik VM, Mantha SSP, Rayani BK. Vascular access in children. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63(9):737-745.

- Taddio A, Ilersich AL, Ipp M, et al; HELPinKIDS Team. Physical interventions and injection techniques for reducing injection pain during routine childhood immunizations: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials and quasi-randomized controlled trials. Clin Ther. 2009;31 Suppl 2:S48-S76.

- Zempsky WT. Pharmacologic approaches for reducing venous access pain in children.

Pediatrics. 2008;122 Suppl 3:S140-S153. - Brenner SM, Rupp V, Boucher J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial to evaluate topical anesthetic for 15 minutes before venipuncture in pediatrics. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(1):20-25.

- Kuo C-C, Feng I-J, Lee W-J. [The efficacy of near-infrared devices in facilitating peripheral intravenous access in children: A systematic review and subgroup meta-analysis.] Hu Li Za Zhi. 2017;64(5):69-80.

- Ng SLA, Leow XRG, Ang WW, Lau Y. Effectiveness of near-infrared light devices for peripheral intravenous cannulation in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;75:e81-e92.

- Francisco MD, Chen W-F, Pan C-T, et al. Competitive real-time near infrared (NIR) vein finder imaging device to improve peripheral subcutaneous vein selection in venipuncture for clinical laboratory testing. Micromachines (Basel). 2021;12(4):373.

- Kim MJ, Park JM, Rhee N, et al. Efficacy of VeinViewer in pediatric peripheral intravenous access: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171(7):1121-1125.

- Doniger SJ, Ishimine P, Fox JC, Kanegaye JT. Randomized controlled trial of ultrasound-assisted vascular access in pediatric emergency departments. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(3):154-159.

- Heinrichs J, Fritze Z, Vandermeer B, et al. Ultrasonographically guided peripheral intravenous cannulation of children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(4):444-454.e1.

- D’Alessandro M, Ricci M, Bellini T, et al. Difficult intravascular access in pediatric emergency department: The ultrasound-assisted strategy (DIAPEDUS Study). J Intensive Care Med. 2024;39(3):217-221.

- Cuper NJ, de Graaff JC, Verdaasdonk RM, Kalkman CJ. Near-infrared imaging in intravenous cannulation in children: A cluster randomized clinical trial. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e191-e197.

- Indarwati F, Mathew S, Munday J, Keogh S. Incidence of peripheral intravenous catheter failure and complications in paediatric patients: Systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102:103488.

- Auerbach MA, Pusic MV, Whitfill T. Intravenous access in pediatric patients. In: Roberts JR, Hedges JR, eds. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Nickel B, Gorski L, Kleidon T, et al; Infusion Nurses Society. Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice. 9th ed. J Infus Nurs. 2021;44(1S Suppl 1):S1-S224.

- Hadaway L. Infiltration and extravasation. Am J Nurs. 2007;107(8):64-72.

- Aria DJ, Vatsky S, Kaye R, et al. Greater saphenous venous access as an alternative in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44(2):187-192.

- Tu Z, Tan Y, Liu L, et al. Ultrasound-guided cannulation of the great saphenous vein in neonates: A randomized study. Am J Perinatol. 2023;40(11):1217-1222.

- Vascular Access — Intravenous, intraosseous, clysis, and peritoneal. In: Iserson KV. eds. Improvised Medicine: Providing Care in Extreme Environments. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Caccialanza R, Constans T, Cotogni P, et al. Subcutaneous infusion of fluids for hydration or nutrition: A review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2018;42(2):296-307.

- Tobias JD, Ross AK. Intraosseous infusions: A review for the anesthesiologist with a focus on pediatric use. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(2):391-401.

- Dornhofer P, McMahon K, Kellar JZ. Intraosseous vascular access. In: StatPearls. Updated May 9, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554373/

- Horton MA, Beamer C. Powered intraosseous insertion provides safe and effective vascular access for pediatric emergency patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(6):347-350.

- de Sá RAR, Melo CL, Dantas RB, Delfim LV. Vascular access through the intraosseous route in pediatric emergencies. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2012;24(4):407-414.

- Taylor RW, Palagiri AV. Central venous catheterization. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(5):1390-1396.

- Ostroff MD, Connolly MW, eds. Ultrasound Guided Vascular Access: Practical Solutions to Bedside Clinical Challenges. Springer International Publishing; 2022.

- Naik VM, Mantha SSP, Rayani BK. Vascular access in children. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63(9):737-745.

- Leblebicioglu H, Erben N, Rosenthal VD, et al. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) national report on device-associated infection rates in 19 cities of Turkey, data summary for 2003-2012. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2014;13:51.

- Verghese ST, McGill WA, Patel RI, et al. Ultrasound-guided internal jugular venous cannulation in infants: A prospective comparison with the traditional palpation method. Anesthesiology. 1999;91(1):71-77.

- Lubitz DS, Seidel JS, Chameides L, et al. A rapid method for estimating weight and resuscitation drug dosages from length in the pediatric age group. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17(6):576-581.

- Wells M, Goldstein LN, Bentley A, et al. The accuracy of the Broselow tape as a weight estimation tool and a drug-dosing guide — A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2017;121:9-33.

- Wells M, Goldstein LN, Bentley A. The accuracy of emergency weight estimation systems in children — A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Emerg Med. 2017;10(1):29.

- Sharp R, Carr P, Childs J, et al. Catheter to vein ratio and risk of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC)-associated thrombosis according to diagnostic group: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7):e045895.

- Milling Jr TJ, Rose J, Briggs WM, et al. Randomized, controlled clinical trial of point-of-care limited ultrasonography assistance of central venous cannulation: The Third Sonography Outcomes Assessment Program (SOAP-3) Trial. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(8):1764-1769.

- Burek AG, Liljestrom T, Dundon M, et al. Long peripheral catheters in children: A scoping review. J Hosp Med. 2022;17(12):1000-1009.

- Qin KR, Pittiruti M, Nataraja RM, Pacilli M. Long peripheral catheters and midline catheters: Insights from a survey of vascular access specialists. J Vasc Access. 2021;22(6):905-910.

- Brass P, Hellmich M, Kolodziej L, et al. Ultrasound guidance versus anatomical landmarks for subclavian or femoral vein catheterization. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(1):CD011447.

- Eisen LA, Narasimhan M, Berger JS, et al. Mechanical complications of central venous catheters. J Intensive Care Med. 2006;21(1):40-46.

- Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(26):2725-2732.

- Lewis K, Spirnak PW. Umbilical vein catheterization. In: StatPearls. Updated March 27, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549869/

- Aziz K, Lee HC, Escobedo MB, et al. Part 5: Neonatal resuscitation: American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S524-S550.

- Shukla H, Ferrara A. Rapid estimation of insertional length of umbilical catheters in newborns. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140(8):786-788.

- Kaur A, Manerkar S, Patra S, et al. Ultrasound-guided umbilical venous catheter insertion to reduce rate of catheter tip malposition in neonates: A randomized, controlled trial. Indian J Pediatr. 2022;89(11):1093-1098.

- Butler-O’Hara M, Buzzard CJ, Reubens L, et al. A randomized trial comparing long-term and short-term use of umbilical venous catheters in premature infants with birth weights of less than 1,251 grams. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e25-e35.

- McConnell S. Emergency procedures. In: Stone C, Humphries RL, Drigalla D, Stephan M, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Pediatric Emergency Medicine. McGraw-Hill Education; 2014.

- Iserson KV, Criss EA. Pediatric venous cutdowns: Utility in emergency situations. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1986;2(4):231-234.

- O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(9):e162-e193.