Update on Pediatric Facial Trauma

November 1, 2025

By Pradeep Padmanabhan, MD, and Tristan Burgess, MD

Executive Summary

- Facial fractures are particularly less common in children who are younger than 5 years of age because of the unique shape of the skull of an infant and young toddler, with the cranium protruding forward in comparison to the facial bones, and the forehead is more likely to bear the impact.

- Nasal bone fracture is the most common facial fracture in both children and adults, responsible for approximately one-third of pediatric emergency department visits related to facial trauma. It is critical to examine the nasal cavity to assess for any deformities or the possibility of a septal hematoma. The most common presentation of a septal hematoma is a septal bulge causing obstruction. This can be differentiated from a deviated septum by palpating the bulge with a cotton tip. A soft and boggy mass is more consistent with a septal hematoma, whereas a firm mass is more likely to be associated with a deviated septum.

- Zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) fractures are the most common fracture patterns associated with high-impact traumas in children, with roughly 15% of pediatric facial fractures being attributed to ZMC fractures. Motor vehicle accidents are the number one cause of ZMC fractures, followed by falls and sports injuries.

- Orbital floor fractures may be easy to miss in children, especially trapdoor fractures. These fractures may be present without obvious signs of periorbital trauma, such as periorbital ecchymosis, edema, conjunctival erythema, or subconjunctival erythema. Hence, orbital floor fractures also are called “white-eyed fracture.” Although obvious signs of trauma may be absent, it is imperative to assess extraocular movements because entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle typically causes restricted extraocular motility and diplopia.

- Children younger than 7-10 years of age are more prone to experience orbital roof fractures, but older children more commonly injure the orbital floor. In association with orbital fractures, 43.4% of children had concomitant intracranial injury and 20% had significant injury beyond the head and neck.

Pediatric facial trauma is common, and clinicians require an understanding not only of common injury patterns, but also of recommended diagnostic strategies and evidence-based management approaches.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, FACEP, Editor

Introduction

In the United States, approximately 30 million children visit an emergency department (ED) every year. Traumatic injuries are the leading cause of death in children and account for 16% to 18% of emergency visits (4.8 to 5.4 million) annually. The head is the most frequently affected in a child during injuries, accounting for approximately 11% of ED visits related to trauma. Facial trauma includes soft tissue, bony, and neurovascular injuries and could involve critical organs, such as the eyes, nose, ears, mouth, and brain.1 Facial trauma can be from either blunt or penetrating trauma. The large majority of facial trauma results from a blunt mechanism.

The management of facial injuries in adolescents is very similar to that in young adults. However, it is important to recognize that injury patterns can vary in infants and young children because of the relatively larger size of the head in proportion to the rest of the body when compared to adults.2 While a majority of injuries are less likely to be life-threatening, they contribute to significant pain, discomfort, and parental anxiety resulting in ED visits.2

The most common cause of injury also can vary depending on a child’s age. As one can imagine, infants and toddlers are very active and mostly clumsy, resulting in falls and injuries. Serious injuries in older children are associated with motor vehicle crashes, bicycle accidents, sports, etc.

Regardless of the mechanism of injury, all significant facial traumas in children have to be managed carefully. Management always begins by evaluating the patency of the patient’s airway, listening to breath sounds, palpating pulses in all four extremities, and analyzing the patient’s mental status.3 The airway is a primary concern in facial trauma. In addition, very young children are at higher risk for rapid decompensation due to hypoxia, hypovolemia, and hypothermia.

Initial Assessment

A systematic evaluation of traumatic patients is necessary to properly triage and treat injuries. The ABCDE protocol should be followed, assessing airway, breathing, circulation, disability and exposure.3 The Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) approach is mostly applicable to children. The main distinction between adults and children lies in the disability category, which primarily relies on acquiring a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score. Evaluating a child’s GCS score is age- and ability-dependent.4 While teens and older children often are able to cooperate with the examination, infants and toddlers typically are unable to provide comprehensive verbal responses.4 In general, one can presume that healthy children older than 2 years of age can localize pain. Children younger than 2 years of age should be assessed differently since they may not be able to provide accurate orientation responses but still may be able to provide appropriate responses to basic questions.4

The facial expressions of a very young child (0-23 months) often can yield clues. For example, a child who is smiling or crying appropriately during the exam is going to be scored higher than a child who exhibits inconsolable crying. The eye opening and the verbal responses, although integral to the GCS, can be difficult to ascertain accurately in children since they can vary as a result of anxiety and the influence of narcotics often used for pain. The motor responses are found to be the most useful and by themselves are a reliable measure of the severity of the injury.5 Using the Pediatric GCS is recommended for children younger than 2 years of age. The airway may have to be secured early, which may be difficult in the setting of severe facial trauma.

Airway in Facial Trauma

As with any trauma patient, evaluation of patients with facial injuries will follow the ATLS guideline.6 Close attention needs to be paid to the airway examination in children in the ED since they are at high risk of needing an emergent airway.6

Securing an airway in severe facial trauma can be difficult. Recent guidelines have revealed that video-assisted laryngoscopy is the preferred method when managing an emergent pediatric airway in severe facial trauma.7 In severe midfacial trauma, oropharyngeal access may not be possible. In emergent cannot intubate/cannot oxygenate situations, access to the airway from the neck is critical to management to prevent a hypoxia-induced cardiac arrest.7 While cricothyroidotomy may be performed in children, younger children (particularly younger than 5 years of age) may benefit from surgical tracheostomy by an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) surgeon (if available) or a transcutaneous needle cricothyroidotomy.7

Evaluation and Management of Pain

Following the primary and secondary survey, one should not overlook treating the child’s pain while continuing with the evaluation since pain control often helps in a better exam. In fact, there are misconceptions that children have a higher pain threshold when compared to adults, or that children will not recall a painful experience, both of which are not true.8

When evaluating a child in pain, one must keep in mind that children of different ages express pain differently.8 Neonates and infants obviously will not be able to voice their pain, but they will have a persistent cry, changes in behavior, or physical signs such as grimacing or frowning throughout the examination.8 As children grow into toddlers and preschoolers, they may even be able to describe it in simple terms or use behaviors to exhibit their pain.8 School-age children should be able to provide more detailed descriptions of pain.8 Finally, adolescents should have a complex understanding of pain and have the ability to communicate their pain levels as effectively as adults.8 A variety of pain scales are available based on the child's age, including the Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS) or FLACC (face, legs, activity, cry, consolability) for infants and toddlers, Wong-Baker FACES or Oucher Scale for preschoolers, and numeric scores for children older than 8 years of age.

Pain control should be early and adequate. Acetaminophen and ibuprofen are effective in mild to moderate pain. Ibuprofen should not be given to infants younger than 6 months of age. When administered carefully, narcotics can alleviate pain quickly. Narcotics, including morphine, generally are safe in children. Young children, particularly infants, should be monitored for respiratory depression. Other measures, including anxiolysis (intranasal midazolam) and child life support, can be crucial, especially in procedures or imaging studies. (See Table 1.)

Table 1. Pain Management |

Ibuprofen

Acetaminophen

Morphine

Fentanyl

Ketamine

Midazolam

Toradol

|

Source: Goyal Gurkha A, Padmanabhan P. Pediatric pain control. Trauma Reports. 2025;26(1):8. |

Facial Fractures

Pediatric facial fractures make up less than 15% of all facial fractures and around 5% of all trauma admissions in the United States.6 Most of these injuries occur during sports, motor vehicle accidents, and falls. Facial fractures are particularly less common in children who are younger than 5 years of age because of the unique shape of the skull of an infant and young toddler.9 In younger children, the cranium protrudes forward in comparison to the facial bones, and the forehead is more likely to bear the impact. Given the relative retrusion of the facial skeleton compared to the cranium, there is a much lower risk of facial fracture.10 Although pediatric facial fractures are rare, they carry significant morbidity. Because of the previously mentioned anatomical differences in pediatric patients, a greater force is required to cause a fracture compared to similar injuries in adults.11 As a consequence of the increased morbidity, pediatric patients with facial fractures are at greater risk for subsequent developmental problems.9

Midfacial Fractures

Midfacial fractures involving the maxillary, zygomatic, nasal, orbital, and/or ethmoid bones can pose challenging clinical problems because of their close proximity to critical underlying structures.10 Midfacial fractures are particularly uncommon prior to the age of 6 years, coinciding with the development and prominence of midfacial structures as the child gets older.11 It is important to know that pediatric midfacial fractures mostly are nondisplaced. This is a consequence of a more flexible facial skeleton in combination with a stronger mandible and maxilla because of children’s undeveloped permanent teeth.11 In addition, children’s maxillary, ethmoid, and paranasal sinuses do not fully develop until the ages of 9, 12, and 18 years, respectively.11 Hence, young children seem to have the ability to absorb blunt trauma and less commonly sustain displaced fractures. Instead, the energy will be transmitted to the supraorbital bar, basilar skull, and intracranially.6

Le Fort Fractures

The Le Fort classification system was created more than a century ago in 1901 by Dr. Rene Le Fort, who described predictable fracture patterns in areas of the midface that are prone to injury.10 His classification system was based on the level and direction of the fracture lines, and the three main identified patterns, which were classified Le Fort I, II, and III.10 Le Fort I fractures involve separation of the lower midface from the zygomatic and nasal complexes, creating what is referred to as a “floating palate.”10,12 Le Fort II fractures extend from the nasofrontal sutures through the zygomaticomaxillary suture and are referred to as the “floating maxilla.”10,12 Lastly, Le Fort III fractures extend from the nasofrontal suture through the floor of the orbit and are known as the “floating face.”10,12

When evaluating patients with a Le Fort fracture, be mindful of the potential risk for hemorrhage.6 Persistent bleeding may require packing, surgical exploration, or, in rare cases, may warrant angiography with embolization.6 A thorough exam is necessary to evaluate for these injuries, including evaluation of the patient’s oropharynx, nasal cavities, and bilateral ear canals. In addition to bleeding, Le Fort fractures also are associated with the risk for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks, which would require urgent neurosurgical evaluation.9 Some patients with a CSF leak may report a metallic or salty taste in their mouth.9 Lastly, palpation of the entire face should be performed to evaluate for any signs of step-off or deformity, which includes assessing for mobility of the maxilla by placing the index finger on the anterior palate and the thumb on the labial vestibule and assessing for any laxity inferiorly, anteriorly, and laterally.9

Le Fort fractures sometimes may require surgical intervention.10 However, some clinicians argue these fractures should be managed conservatively because of the increased potential for bone growth in the pediatric population when compared to their adult counterpart.11 In general, most of these fractures are managed conservatively in children. However, early consultation with the maxillary and facial surgeons for ongoing guidance and management is necessary.6 It is important to secure the airway early in fractures with significant or persistent bleeding. Le Fort fractures have an increased rate of associated intracranial injury, which will require additional imaging and close observation/hospitalization.9

Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures

Zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) fractures are the most common fracture patterns associated with high-impact traumas in children, with roughly 15% of pediatric facial fractures being attributed to ZMC fractures.6 Motor vehicle accidents are the number one cause of ZMC fractures, followed by falls and sports injuries.13 ZMC fractures are very uncommon in children younger than the age of 5 years.13 Boys are more involved, with the male:female ratio ranging up to 2-6:1.13 The ZMC is the anatomical area involving the zygoma, the maxilla, and the orbital floor.6

The examination for any patient with a facial injury should include a detailed visual inspection to evaluate for any possible deformity.6 The child should be inspected from a superior, inferior, frontal, and lateral perspective, with the superior perspective providing the best view to evaluate for posterior displacement or facial flattening.6 During palpation, it is important to examine intraorally since many of these fractures may have coexisting injuries, such as intraoral ecchymosis and dentoalveolar fractures.6

A thorough eye examination should be performed as well, given the involvement of the orbital floor in the ZMC. Complications such as diplopia, unequal pupils, enophthalmos, subconjunctival hemorrhage, inferior displacement of the globe, and inferior rectus muscle entrapment may be recognized.6 If there are concerns for decreased extraocular movements, a forced duction test can help confirm the possibility of muscle involvement.6 If there are clinical findings (as mentioned earlier), ophthalmology should be consulted for a thorough evaluation immediately. Stable and nondisplaced fractures without complications can be managed conservatively.

A complete neurological examination is essential in complex facial injuries. Given its close proximity to the ZMC, the infraorbital nerve often is involved in these injuries.6 Infraorbital nerve injuries can present with numbness/ paresthesias to the infraorbital region, the maxilla, and the ipsilateral nasal region.6 There may be associated trismus with these injuries as well, which is due to medial displacement of the zygoma, causing a physical stop/obstruction when attempting to open the mandible.6 Computed tomography (CT) imaging is necessary since plain radiographs often do not identify or delineate the injuries adequately.6 In severe injuries, CT angiogram may be performed to evaluate for any underlying vascular injury. Branches of the internal and external carotid arteries that underlie bony structures are vulnerable during severe facial trauma.14

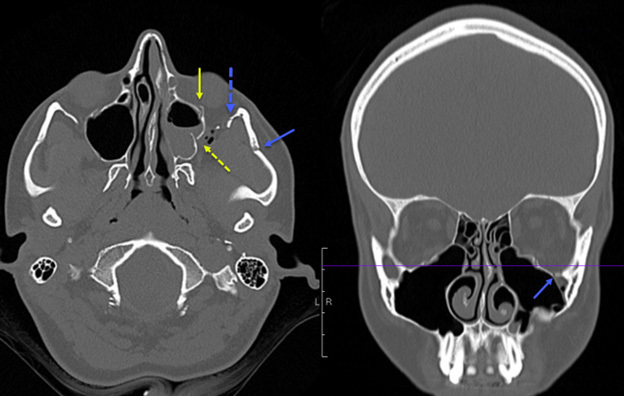

Figure 1 shows a slice of a CT scan in both the axial and coronal planes that provides an example of a ZMC fracture in a pediatric patient. The image demonstrates an anterior and posterior maxillary sinus wall fractures, zygomatic arch fracture, inferior orbital rim fracture, and lateral orbital rim fracture.

Figure 1. Computed Tomography Scan of Zygomaxillary Complex Fracture |

|

The image demonstrates an anterior and posterior maxillary sinus wall fractures, zygomatic arch fracture, inferior orbital rim fracture, and lateral orbital rim fracture. Image courtesy of Mantosh S. Rattan, MD, Radiologist, Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Children’s Hospital, Orlando, FL. |

As previously stated, ZMC fractures are associated with a high-energy mechanism of injury. Children are at a higher likelihood of severe aesthetic and functional complications.15 Children with ZMC fractures often are managed conservatively in an attempt to prevent disruption of midface and dental development.6 However, there are situations that may warrant surgical management.15 Hence, early consultation with the experts, either oral and maxillofacial surgery or plastic surgery, will help guide management in the ED.15

Nasal Bone Fractures

Nasal bone fracture is the most common facial fracture in both children and adults, responsible for approximately one-third of pediatric ED visits related to facial trauma.16,17 Mechanisms include sports, motor vehicle accidents, falls, etc.16 These fractures occur more commonly in males.17 Although most of these fractures occur mostly in isolation, a thorough exam is important to identify additional injuries in children.17 History should include mechanism of injury, timing, presence of nasal obstruction, and determination of any subjective change in appearance that has occurred.17

It is critical to examine the nasal cavity to assess for any deformities or the possibility of a septal hematoma.17 The most common presentation of a septal hematoma is a septal bulge causing obstruction.16 This can be differentiated from a deviated septum by palpating the bulge with a cotton tip.16 A soft and boggy mass is more consistent with a septal hematoma, whereas a firm mass is more likely to be associated with a deviated septum.16 Worsening or severe pain may indicate the formation of a septal hematoma.17 If a septal hematoma is identified, it should be drained immediately and the wound should be packed.16 Patients also should be discharged with instructions to follow up with ENT in 24-48 hours.15

Patients with nasal injuries have a higher chance of epistaxis because of the presence of Kiesselbach’s plexus with abundant blood flow. It is important to check for the possibility of a coexisting CSF leak.17 The diagnosis of CSF leak can be challenging to differentiate from normal nasal secretions, especially in the setting of facial/nose trauma.17 A “halo sign,” which is identified by adding a few drops of the secretions on a filter paper and looking for a central area of blood surrounded by a clear outer ring, presumed to be from CSF.17 However, this test has poor sensitivity and specificity since water, saline, and other watery substances can cause a false positive.17 Other tests include testing the secretions for glucose or beta-2-transferrin; however, the former also has a low sensitivity/specificity and the latter requires 1 mL of fluid and can take up to a week to result, which is not always feasible during an ED visit.17 Maybe, the simplest way to evaluate for a CSF leak may be to observe the patient and obtain cross-sectional imaging.17

While multiple imaging modalities can be used for evaluating nasal injuries, plain X-rays often are sufficient.18,19 Even though the sensitivity of plain films is around 65.7%, CT scans should be used sparingly and only when serious/complex injuries are suspected because of the risk of radiation exposure in children.20 Ultrasound can detect nasal fractures with increased accuracy (sensitivity 90%, specificity 89%) than plain film X-rays.20

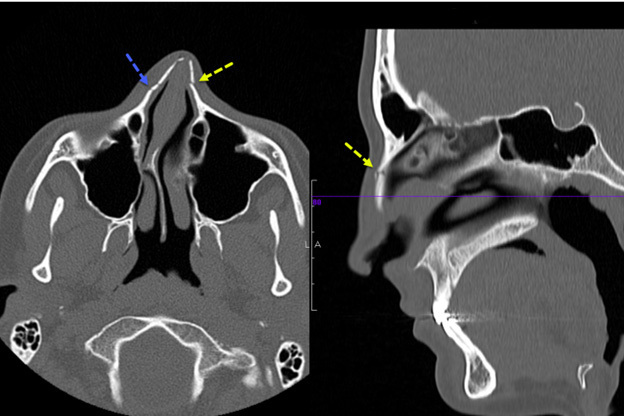

Figure 2 presents an example of a nasal bone fracture on CT scan in a pediatric patient in both the axial and sagittal planes. This example shows an angulated nasal bone fracture with widening of both nasomaxillary sutures.

Figure 2. Computed Tomography Scan of Nasal Bone Fracture |

|

This image shows an angulated nasal bone fracture with widening of both nasomaxillary sutures. Image courtesy of Mantosh S. Rattan, MD, Radiologist, Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Children’s Hospital, Orlando, FL. |

If no significant deformity or nasal/septal bone deviation is identified, conservative management is adequate.17 Since significant soft tissue swelling can mask any underlying deformity, close follow-up should be considered.17 Infants are nose breathers, so they should be observed to ensure they are able to breathe adequately during feeding.17

Typically in nasal fractures that need correction, fracture reduction is accomplished after three to five days once swelling has subsided. It is important not to delay beyond seven to 10 days from the incident because of children’s ability to heal quickly and fractured segments becoming immobilized.17

Naso-Orbital-Ethmoid Fracture

Naso-orbital-ethmoid (NOE) fractures are serious injuries that involve the superior aspect of the midface.6 These fracture patterns typically are associated with high-impact trauma but, fortunately, are rare in children, accompanying less than 1% of pediatric facial fractures.6 NOE fractures isolate and destabilize the portion of the midface connecting the forehead to the lateral nasal region, medial orbits, and maxillary buttress.6,21

There are many classifications that can be used when describing NOE fractures. However, most classifications are tailored to adults and older children, rather than the younger pediatric population because of their differing anatomy.6 The Burstein classification was created to describe NOE fracture patterns that were sustained by young children.6 Burstein type I fracture is a unilateral fracture involving the medial aspect of the frontal bone as well as the superior aspect NOE complex.6 Burstein type II fracture also is unilateral and involves the superior orbital rim and extends into the medial frontal bone.6 Finally, Burstein type III is bilateral and involves both superior orbital rims, superior NOE complex, and the frontal bones.6 (See Table 2.)

Table 2. Burstein Classification of Naso-Orbital-Ethmoid Fractures |

Type I

Type II

Type III

|

Examination findings that can increase suspicion for NOE fractures include posterior displacement of the nose in the nasofrontal region, enophthalmos, and telecanthus, which is an increased distance between the medial eyelids with normal distance between the pupils.6 As with other complex fractures that require a high-force trauma, NOE fractures have been associated with intracranial hemorrhage, septal hematoma, or dural injury with associated CSF leak.6 Therefore, it is imperative to evaluate for any signs of basilar skull fracture. In addition, evaluation of the medial canthal tendon (MCT) injury should be performed.6 Assessment for a “ bowstring sign” is performed by using two fingers of one hand to transverse the nasal bridge while using the other hand to pull laterally on the lateral canthus.6 A positive test indicative of injury results in displacement of the MCT laterally.6 Lastly, given the proximity to the lacrimal duct, a thorough exam to ensure patency of the duct is critical. If the lacrimal duct appears to be involved, an ophthalmology consultation is recommended.6

The mainstay of management for NOE fractures involves restoring the intercanthal distance, correct positioning of the orbit, providing nasal support, and preserving the nasal tip projection.6 Prompt oromaxillary surgery consultation and evaluation is warranted even though most children are treated nonoperatively.21

Orbital Trauma

Trauma involving the eyes and orbits is the leading cause of trauma-related monocular blindness in children.22 Orbital fractures occur more frequently in boys.23 The type of orbital fracture varies with age. Children younger than 7-10 years of age are more prone to experience orbital roof fractures, but older children more commonly injure the orbital floor.23 The orbit is made of seven bones — frontal, maxillary, zygomatic, ethmoid, lacrimal, palatine, and the greater and lesser wings of the sphenoid — which form the four orbital walls, including the roof, floor, medial, and lateral.23

Similar to other pediatric facial fractures, a strong force is required to cause orbital injuries in children.7,9,23 In association with orbital fractures, 43.4% of children had concomitant intracranial injury and 20% had significant injury beyond the head and neck.23 The risk of concomitant injury and, therefore, complications is increased when multiple orbital wall fractures are involved.23

Imaging studies in correspondence with clinical findings is the most common way to diagnose traumatic orbital injuries in pediatrics.24 CT scan is the preferred imaging modality to diagnose these injuries.24 Specifically, CT scan of the orbits can provide thinner slices of both the eyeball and eye socket to diagnose injuries with increased accuracy when compared to normal CT scan. While ultrasound can be helpful, it is operator-dependent and can be difficult to perform in children because of pain and anxiety. CT imaging offers accurate results and is the gold standard.24

Orbital Roof Fractures

The orbital roof can be fractured with orbital trauma.25 The most common orbital roof fracture extends to the frontal bone through the supraorbital foramen.23 Up to 40% of children presenting with orbital roof fractures may have a second orbital wall fracture.23

The superior oblique muscle, which originates in the upper medial side of the orbit, is responsible for abduction, depression, and internal rotation of the eye.23,25 Orbital roof fractures can be complicated by entrapment of the superior oblique muscle or tendon, restricting its movement, which leads to difficulty with elevation while trying to move the eye inward (adduct).23,25 This is termed “Brown syndrome.”23

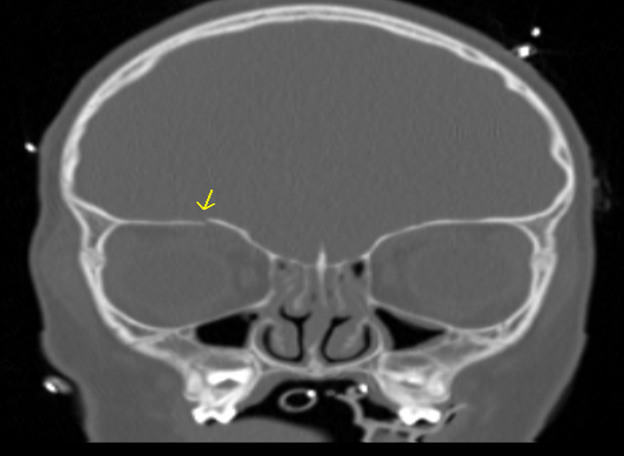

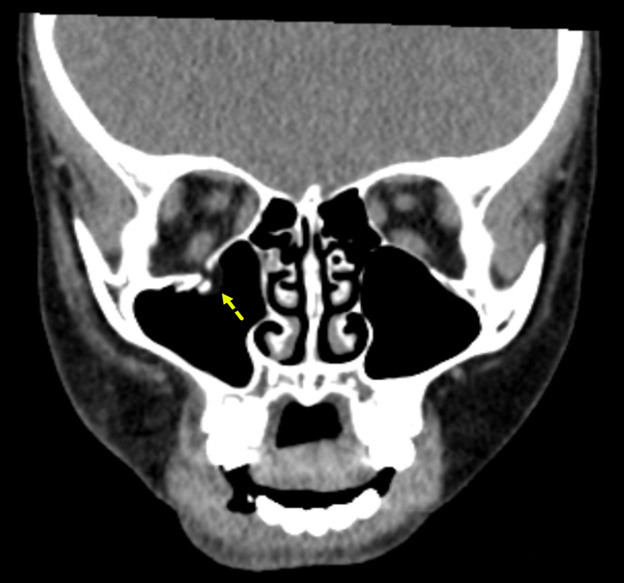

Figure 3 shows an example of an orbital roof fracture in a pediatric patient in the coronal plane. The image demonstrates a mildly displaced fracture.

Figure 3. Orbital Roof Fracture |

|

The image demonstrates a mildly displaced orbital roof fracture. Image courtesy of Mantosh S. Rattan, MD, Radiologist, Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Children’s Hospital, Orlando, FL. |

A “blow-in” fracture is the result of a supraorbital force that is directed below, causing collapse of the orbital roof.23 Children often will present with periorbital edema and ecchymosis, upper eyelid pseudoptosis, restriction of upper gaze/elevation, dystopia, and diplopia.23

Orbital Medial Wall Fractures

Orbital medial wall fractures are prone to entrapment of the medial rectus muscle, which is responsible for adduction (inward movement) of the eye.23 The child may present with diplopia (double vision) with both medial and lateral eye movement.23 Children also may have associated nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and bradycardia due to oculocardiac reflex.

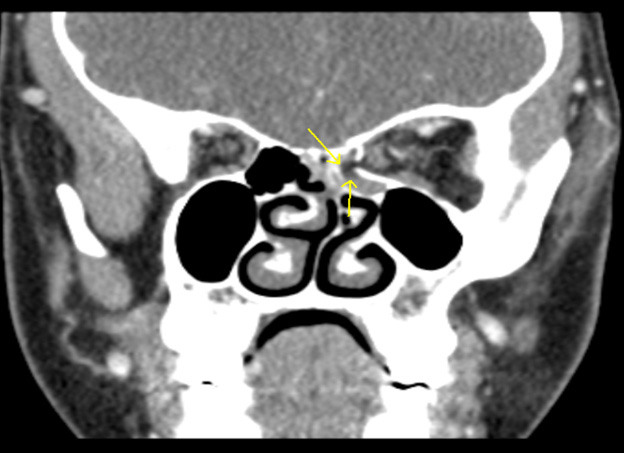

Figure 4 shows an example of a coronal view of a medial orbital wall fracture in a pediatric patient. The image represents a comminuted fracture of the medial orbital wall/lamina papyracea with herniated intra-orbital fat and distortion of the normal morphology of the medial rectus muscle.

Figure 4. Medial Orbital Wall Fracture |

|

The image shows a comminuted fracture of the medial orbital wall/lamina papyracea with herniated intra-orbital fat and distortion of the normal morphology of the medial rectus muscle. Image courtesy of Mantosh S. Rattan, MD, Radiologist, Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Children’s Hospital, Orlando, FL. |

Orbital Floor Fractures

Pediatric orbital floor fractures often are designated as either open door or trapdoor fractures.23 Orbital trapdoor, as the name suggests, refers to a fracture with a soft tissue entrapment at the fracture site, whereas open door refers to an unentrapped fracture.23,26 Trapdoor fractures result from a sudden increase in orbital pressure, causing a linear fracture along the inferior wall of the orbit.27 This is comparable to orbital blowout fractures in adults; however, in children, the elastic nature of their bones causes the infraorbital floor to temporarily displace outwardly before recoiling back to its original position, which then can entrap soft tissue or extraocular muscles.27 Entrapment usually involves the inferior rectus muscle, potentially leading to ischemia and infarction of the muscle, causing permanent limitation of eye ball movement.23,26,27

Orbital floor fractures may be easy to miss in children, especially trapdoor fractures. These fractures may be present without obvious signs of periorbital trauma such as periorbital ecchymosis, edema, conjunctival erythema or subconjunctival erythema.23,26,27 Hence, orbital floor fractures also are called “white eyed fracture.”26,27 Although obvious signs of trauma may be absent, it is imperative to assess extraocular movements as entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle typically causes restricted extraocular motility and diplopia, in addition to pain.23,27 Another manifestation to consider with trapdoor fractures is the oculocardiac reflex.23 The oculocardiac reflex is a response from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve sending signals to the motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, resulting in increased parasympathetic tone and manifesting as bradycardia, nausea, vomiting, and syncope.23,27 In facial injuries, nausea and vomiting alone has a 83.3% positive predictive value for trapdoor fractures.23

CT scan plays a crucial role in detection of trapdoor fractures, as even minor displacement of the bony fragments can be identified.26 However, when muscle gets entrapped in trapdoor fractures, it may be engulfed by the fat between the muscle and bone.23 This makes it difficult for muscle to be visualized on CT scans, which often is missed in up to 50% of cases of muscle entrapment.23 A proper clinical examination is considered the primary diagnostic method of trapdoor fractures. Therefore, it is vital to perform a complete physical examination, including visual acuity and extraocular movements in patients with ocular trauma.23,27 Early surgical intervention in the first 48 hours is critical for achieving rapid and improved recovery from diplopia and restricted extraocular movements in children.27

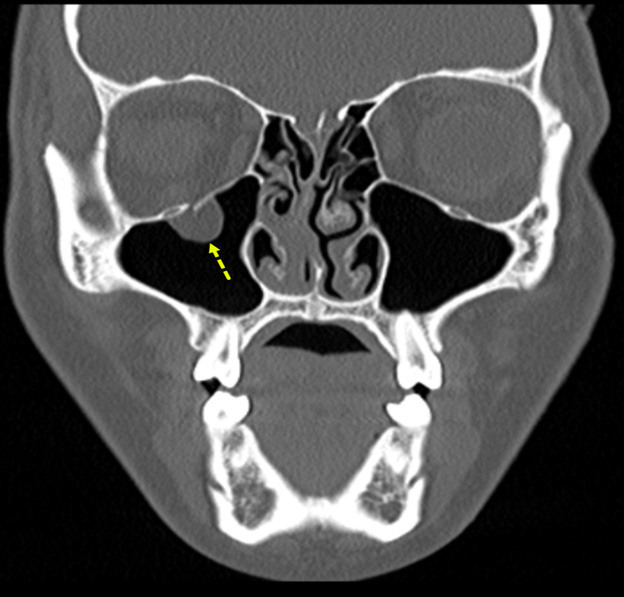

Figure 5 shows an example of an orbital floor fracture without evidence of entrapment in a pediatric patient in the coronal plane. In comparison, Figure 6 shows an entrapped orbital floor fracture in the bone window. The image reveals evidence of a non-displaced orbital fracture with entrapped intra-orbital fat.

Figure 5. Orbital Floor Fracture Without Evidence of Entrapment |

|

The image shows a displaced orbital floor fracture with no evidence of entrapment. Image courtesy of Mantosh S. Rattan, MD, Radiologist, Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Children’s Hospital, Orlando, FL. |

Figure 6. Entrapped Orbital Floor Fracture |

|

The image shows evidence of a non-displaced orbital fracture with entrapped intra-orbital fat (bone window). Image courtesy of Mantosh S. Rattan, MD, Radiologist, Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Children’s Hospital, Orlando, FL. |

Ocular Injuries

As previously mentioned, ocular trauma is the leading cause of monocular blindness in children.22 In fact, the American Academy of Pediatrics reported that 66% of all eye trauma occurred in individuals younger than 16 years of age, with the highest frequency recorded in ages 9 to 11 years.28 In particular, ocular injuries are more common in lower socioeconomic settings where there is limited access to health promotion and accident prevention resources.29

Ocular injuries include corneal damage, lens opacities, lens dislocation, hyphema, glaucoma, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal tears, retinal detachment, open globe injuries, and traumatic optic neuropathies.30 While each of these injuries will not be discussed at length, it is important to know that ocular injuries must be considered in the event of facial trauma involving the orbit because these injuries can result in loss of vision.31 Obtaining a visual acuity examination will be critical to assess for any ophthalmologic injury; however, having a reliable visual acuity is not always possible when evaluating children, especially after trauma.31 Hyphema (blood in the anterior chamber) or 360-degree circumferential subconjunctival bleed portends a serious injury. An immediate ophthalmologist consultation is warranted except for very minor issues (e.g., corneal abrasion).31

Soft Tissue Injuries

Facial lacerations are among the most common injuries in children presenting to the ED.32 Interestingly, a large portion of these injuries come from dog bites.33 The lack of caution and the short stature of young children makes them particularly vulnerable for facial dog bite injuries.33

The management of maxillofacial soft tissue injuries in children provides unique challenges, since children still are growing and developing.2 Improper management of soft tissue injuries in children results in a higher risk of complications, such as growth disturbances and cosmetic changes.2 All abrasions, lacerations, and contusions should be carefully examined, with any obstructions such as bandages or secretions removed to assess all tissue loss, viability, and the depth of all wounds.2 As previously discussed with bony injuries, it is critical to assess for any motor function or neurological abnormalities for soft tissue injuries as well.2 Any changes to the patient’s neurological status change management considerably.2

Most facial lacerations, including in the pediatric population, can be safely managed in the ED. However, there are existing criteria for which a plastic surgeon or ophthalmologist should be involved in the laceration repair.34 Lacerations that can be repaired in the ED include any simple laceration less than 5 cm that will require a one or two layer closure, lacerations through the vermilion border, scalp lacerations, and simple lacerations of the oral mucosa and tongue.34 Indications for consultation of a plastic surgeon include full-thickness lacerations, eyelid lacerations involving the tear duct, or complex lacerations that include the vermilion border, any laceration that is greater than 5 cm, lacerations with extensive contamination, stellate lacerations, lacerations with missing tissue/difficult approximation, lacerations including muscle tissue, ear or nasal lacerations that include cartilage, facial nerve injury, and nostril/eyelid lacerations.34 Lastly, any laceration that includes or comes within 2 mm of the medial canthus should be repaired by an ophthalmologist.34

Repairing even a simple facial laceration can be extremely traumatic and anxiety provoking for young children; therefore, children often require anxiolysis or procedural sedation to tolerate the procedure.32 Pediatric procedural sedation generally refers to moderate sedation, which is defined as a drug-induced depression of consciousness during which patients maintain the ability to respond purposefully to verbal stimuli with or without the assistance of tactile stimulation.35 When choosing drugs for procedural sedation, it is important to consider many factors, such as the length of the procedure and the type of procedure, and whether it is painful or not.36 Benzodiazepines, such as midazolam or versed, are used for anxiolysis and can be given intranasally or orally.36 Children who receive these medications should be carefully monitored during the procedure, primarily for respiratory depression. Procedural sedation is very safe and commonly used in children’s hospitals.

Ketamine has been used increasingly for repair of facial lacerations in children. Ketamine combines properties of sedation, amnesia, and analgesia while also increasing and maintaining respiratory drive, cardiovascular tone, and cerebral blood flow.36 An additional advantage of ketamine is that it can be administered through many routes (intravenous, intramuscular, and intranasal).

Once an adequate environment has been achieved with or without sedation, repairing any soft tissue injury to the face should be completed with a great deal of caution. While this is a reasonable consideration, it has been noted that facial lacerations repaired by emergency medicine physicians have had outcomes equal to or greater than lacerations that have been repaired by plastic surgery colleagues.37

Conclusion

Facial trauma in children should be evaluated carefully. The appearance of a simple soft tissue injury may mask underlying significant bony injury. It is important to note that children may decompensate late and initial normal vital signs can create a false sense of security. Evaluation and early protection of the airway is paramount, since bleeding and significant facial swelling can quickly lead to respiratory compromise. It often is difficult to examine the child thoroughly because of anxiety and pain. The anxiety and pain of the child should be addressed to accomplish a thorough clinical exam. Anxiolysis using benzodiazepines (e.g., midazolam) is very helpful in taking care of children with significant trauma. Be careful not to dismiss distress in children by attributing it to anxiety and not perform a complete evaluation, including imaging.

If the history is inconsistent in very young children, one should consider non-accidental trauma and consider performing additional images, such as skeletal survey, and seeking additional resources (child advocacy, social work, etc.). Early, appropriate consultation with subspecialists/surgeons is helpful in case surgical intervention is needed.

Pradeep Padmanabhan, MD, is Associate Program Director, Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellowship, Dayton Children's Hospital; Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine, Dayton, OH.

Tristan Burgess, MD, is Emergency Medicine Resident, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine, Dayton, OH.

References

1. Rogan DT, Fang A. Pediatric facial trauma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. July 25, 2023.

2. Rarasati SA, Sylvyana M, Putri DM. Pediatric facial trauma management: Emergency case in a toddler. Dental Journal (Majalah Kedokteran Gigi). 2024;57(4):310-316.

3. Radvinsky DS, Yoon RS, Schmitt PJ, et al. Evolution and development of the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol: A historical perspective. Orthopedics. 2012;35(4):305-311.

4. Jain S, Margetis K, Iverson LM. Glasgow Coma Scale. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing: June 23, 2025.

5. Acker SN, Ross JT, Patrick DA, et al. Glasgow motor scale alone is equivalent to Glasgow Coma Scale at identifying children at risk for serious traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(2):304-309.

6. Bhat A, Lim R, Egbert MA, Susarla SM. Pediatric Le Fort, zygomatic, and naso-orbito-ethmoid fractures. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2023;35(4):563-575.

7. Zimmerman L, Maiellare F, Veyckemans F, et al. Airway management in pediatrics: Improving safety. J Anesth. 2025;39:123-133.

8. Gurkha AG, Padmanabhan P. Pediatric pain control. Trauma Reports. 2025;26(1):1-23.

9. Macmillan A, Lopez J, Luck JD, et al. How do Le Fort-type fractures present in a pediatric cohort? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;76:1044-1054.

10. Otero SP, Cassidy MF, Morrison KA, et al. Analyzing epidemiology and hospital course outcomes of LeFort fractures in the largest national pediatric trauma database. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2024;17:NP154-NP162.

11. Juncar RI, Moca AE, Juncar M, et al. Clinical patterns and treatment of pediatric facial fractures: A 10-year retrospective Romanian study. Children (Basel). 2023;10(5):800.

12. Phillips BJ, Turco LM. Le Fort fractures: A collective review. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2017;5(4):221-230.

13. Shakilur Rahman AFM, Jannat T, Haider IA. Etiology and patterns of pediatric maxillofacial fractures: A retrospective analysis at a tertiary level health-care center in Bangladesh. J Dental Research Review. 2023;10(3):155-160.

14. Koeing ZA. Shabih S, Uygar HS. Blunt vascular injuries of the face and scalp: Systematic review and introduction of a grading scheme and treatment algorithm. J Craniofac Surg. 2025;36:1560-1564.

15. Zhang D, Lv K. Management of zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures in children. J Craniofac Surg. 2025;36:e653-e654.

16. Thompson J, Pulkki K, Giles SM. The occasional nasal septal hematoma management. Can J Rural Med. 2025;30(1):39-43.

17. Tolley PD, Massenburg BB, Manning S, et al. Pediatric nasal and septal fractures. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2023;35(4):577-584.

18. Sunder R, Tyler K. Basal skull fracture and the halo sign. CMAJ. 2013;185(5):416.

19. Leapo L, Uemura M, Stahl MC, et al. Efficiency of X-ray in diagnosis of pediatric nasal fracture. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;162:111305.

20. Noy R, Gvozdev N, Ilivitzki A, et al. Ultrasound for management of pediatric nasal fractures. Rhinology. 2023;61(6):568-573.

21. Luthringer MM, Oleck NC, Mukherjee TJ, et al. Management of pediatric nasoorbitoethmoid complex fractures at a Level 1 trauma center. Am Surg. 2022;88(7):1675-1679.

22. Farag AA, Ahmed Amer AA, Bayomy HE, et al. Pattern of eye trauma among pediatric ophthalmic patients in upper and lower Egypt: A prospective two-center medicolegal study. J Public Health Res. 2024;13(3):1-14.

23. Hassan B, Liang F, Grant MP. Pediatric orbital fractures. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2023;35(4):585-596.

24. Pirhan D, Subasi S, Musaoğlu BK, et al. The relationship between computed tomography findings and ocular trauma and pediatric ocular trauma scores in pediatric globe injuries: Does imaging have prognostic and diagnostic value? Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2023;29(11):1280-1287.

25. Yalamanchili SP, Ibrahim ZA, Wladis EJ. Traumatic orbital roof fracture with superior rectus entrapment in a pediatric patient. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;40(2):e45-e48.

26. Hakkou Z, El Zouiti Z, Elayoubi F, Tsen AA. Pediatric trapdoor fracture of the orbital floor with a tear-drop sign: A case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2024;20(3):1403-1405.

27. Eshraghi B, Khademi B, Rafizadeh SM, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in orbital trapdoor fracture: A multi-center study. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024;29(7):1-8.

28. Axa AP, Amiruddin PO, Caesarya S. Clinical characteristics and management of pediatric eye trauma in national tertiary hospital in Indonesia. Jurnal Profesi Medika. 2024;18(2):161-169.

29. Zepeda-Romero LC, Saucedo-Rodriguez LR, Becerra-Cota M, et al. Clinical characteristics and functional outcome of pediatric ocular trauma in a third reference hospital in Guadalajara, Mexico. Bol Méd Hosp Infant Méx. 2022;79(1):26-32.

30. Farag AA, Ahmed Amer AA, Bayomy HE, et al. Pattern of eye trauma among pediatric ophthalmic patients in upper and lower Egypt: A prospective two-center medicolegal study. J Public Health Res. 2024;13(3):1-14.

31. Biçer GY, Zor KR. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of pediatric patients with post-traumatic open globe injury. Cukurova Medical Journal. 2023;48(3):789-796.

32. Lee D, Yeo H, Lee Y, et al. A survey on procedural sedation and analgesia for pediatric facial laceration repair in Korea. Arch Plast Surg. 2023;50(1):30-36.

33. Mattice T, Schnaith A, Ortega HW, et al. A pediatric Level III trauma center experience with dog bite injuries. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2024;63(7):914-920.

34. Silva ONN, Mills DA, Fleegler EW, et al. Standardizing pediatric facial laceration management to advance equity and education. J Surg Educ. 2025;82(9):103613.

35. Hall D, Moriarty T, Ronald D, et al. The landscape of pediatric procedural sedation in the United Kingdom and Irish emergency departments; an international survey study. Paediatr Neonatal Pain. 2024;7(1):e12132.

36. Tom D, Reeves S. Pediatric procedural sedation. Pediatr Ann. 2024;53(9):e324-e329.

37. Reiss E, Gronovich Y, Heiman E, et al. Cosmetic outcomes of simple facial laceration suturing in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Med J. 2024;11(2):65-70.