Managing Pediatric Diabetic Emergencies

November 1, 2025

Executive Summary

- Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disorder that is caused by the destruction of pancreatic beta cells. Beta cells are contained within the pancreatic islet and are responsible for producing insulin.

- Numerous factors, such as younger age (< 2 years of age) or non-Hispanic Black race, were identified as being associated with delays in diagnosis. In addition, nonspecific symptoms, such as nausea and abdominal pain, may mask the presentation, which requires a higher degree of suspicion by providers. Complications of delayed diagnosis included longer hospital stays, increased admission to intensive care units, and even mechanical ventilation.

- Type 1.5 diabetes, also known as latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA), encompasses characteristics of both type 1 and 2 diabetes. Similar to type 1 diabetes, LADA occurs because of antibodies attacking the beta cells in the pancreas, causing cessation of insulin production. This form of diabetes usually begins in adulthood and generally is diagnosed between 30-50 years of age.

- Another form of diabetes, called type 3C, develops when other diseases affect the pancreas and its ability to function. The disorders that most commonly cause type 3C diabetes include cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis, or a pancreatectomy.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a feared complication that can occur for several reasons in patients with diabetes. DKA is the leading cause of mortality in those patients younger than 24 years of age. The hallmarks of DKA include hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, and ketosis.

- Early identification and treatment of hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome (HHS) can decrease lengths of stay and improve patient outcomes. HHS typically has a slower onset than DKA and can take days to weeks to develop. Profound dehydration is characteristic of HHS. In addition, patients will be hyperglycemic and likely will have altered mental status. In contrast with DKA, patients do not have ketosis or acidosis.

- It is crucial to know patients’ potassium levels prior to initiating an insulin drip. Patients often require potassium replacement before or with insulin. While potassium may appear normal on the metabolic panel, it is important to remember that there is a total body potassium deficit of roughly 3 mEq/kg to 6 mEq/kg in DKA. If insulin is started prior to obtaining and repleting the potassium level, it will drive the extracellular potassium into the cells, further exacerbating the hypokalemia, which can be detrimental.

- Many providers and experts are now advocating for the two-bag method when treating DKA. This is an approach that uses two separate bags of intravenous fluids (IVF) that are running simultaneously and at different proportions based on the patient’s current BG levels. This approach involves one bag of IVF with dextrose and one without. The fluids will collectively run at 1.5 times the maintenance IVF rate to avoid fluid overload. Typically, clinicians use 0.9% normal saline with 40 mEq/L of potassium added and a bag of dextrose 10%. Once the fluids are running at 1.5 times the maintenance rate, insulin infusion can be started. The proportions in each of the bags are readjusted based on the patient’s blood glucose levels, always ensuring that the total fluid rate stays at 1.5 times the maintenance rate for that child.

- Risk factors that are associated with increased risk of cerebral edema secondary to DKA treatment include severe acidosis or dehydration, age younger than 3 years, pH < 7.0, failure of sodium to correct despite fluid resuscitation, and elevated kidney function.

Managing pediatric diabetic emergencies is challenging. Children, especially those younger than 2 years of age, may present with subtle symptoms. Diagnosis and management must be initiated intentionally and monitored carefully to optimize each child’s outcome. The authors provide an evidence-based approach to recognition, diagnosis, and management of diabetes in children.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, FAAP, FACEP, Editor

By Courtney Botkin, DO, and Daniel Migliaccio, MD, FPD, FAAEM

Introduction and Epidemiology

Type 1 diabetes also is known as juvenile diabetes or insulin-dependent diabetes because of the typical age at diagnosis and treatment. Type 1 diabetes usually has an abrupt onset because of a complete termination of insulin production. It remains the most common pediatric endocrine disorder, affecting roughly one in 400 children. There was a 21% increase in type 1 diabetes diagnoses and a 31% increase in type 2 diabetes diagnoses from 2001-2009 alone.1 Type 2 diabetes is significantly more common, accounting for 90% of diabetes diagnoses. Type 1 diabetes accounts for 8% of cases, and the remaining 2% is associated with obscure disorders that can cause pancreatic dysfunction and, subsequently, decreased insulin production.2

Episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) occur around 6% to 8% annually in children with known type 1 diabetes. Roughly two-thirds of the time that children present to the emergency department (ED) in DKA, they already have been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes.2 However, there is evidence that as many as 34% of children are initially diagnosed with type 1 diabetes after presenting to the ED because of signs and symptoms of DKA. This is why a heightened suspicion and clinical knowledge is necessary — delayed diagnosis in pediatric patients can be detrimental.1,3

Many studies have investigated the consequences and outcomes of delayed diagnosis of diabetes in the pediatric population during ED visits. One study evaluated 11,716 cases to determine the frequency of pediatric patients presenting to the ED within the two weeks prior to the episode of DKA that established their type 1 diagnosis.3 They found that 14% to 38% of new diagnoses were delayed, and 2.9% episodes of DKA were caused by delayed diagnoses of new-onset diabetes in these patients. Of these delayed diagnoses, 94.2% of pediatric patients presented to the ED within the preceding 14 days of their diagnosis.

This means almost all the pediatric patients who would eventually be diagnosed with type 1 diabetes were not only in contact with healthcare, but in the two weeks prior to diagnosis they were in the ED seeking care. This study also revealed that 5.3% of these children even presented to the ED twice in the two weeks leading up to their diagnosis.3 This demonstrates the importance of ED providers to remain vigilant in identifying symptoms, especially for repeat visits. The most common associated symptoms include infectious symptoms such as nausea and vomiting suggesting abdominal etiology, which is why providers should have a high index of suspicion.

Numerous factors, such as younger age or non-Hispanic Black race, were identified as being associated with delays in diagnosis. Data collection particularly has identified that children younger than 2 years of age presenting with new-onset diabetes are at a significantly increased risk of delayed diagnosis, given that symptoms may be nonspecific. In addition, children cannot communicate well at that age, adding further challenges for clinicians. Identifying and addressing delays in clinical practice is crucial because delays in this study revealed evidence of increased complication rates, as one would expect. In this study, complications of delayed diagnosis included longer hospital stays, increased admission to intensive care units, and even mechanical ventilation.3 While delays in diagnosis may not seem to significantly affect clinical outcomes, evidence suggests there is an increased association in patients presenting with DKA at the time of diagnosis with increased mortality and suboptimal glycemic control throughout their lives.

Pathophysiology

Traditionally, children were thought to only get type 1 diabetes. However, over the past few decades, the number of cases of type 2 diabetes in children has increased. There are a number of genes that are found to be linked with type 1 diabetes, although type 2 has a greater association with family history. In addition, obesity, waist circumference, and ethnicity are shown to be associated with increased risks for type 2 diabetes. The ethnicities that are shown to have increased association rates with type 2 diabetes include Chinese, south Asian, Black African, and African-Caribbean.2

Type 1 Diabetes

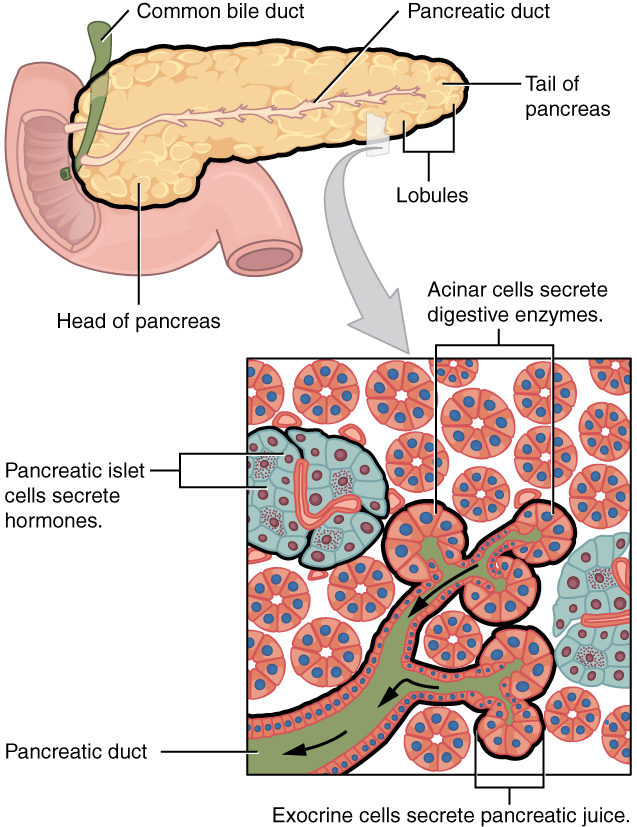

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disorder that is caused by the destruction of pancreatic beta cells. Beta cells are contained within the pancreatic islet and are responsible for producing insulin. (See Figure 1.) When these cells are damaged, the lack of insulin prohibits glucose from entering cells and being used, resulting in hyperglycemia. While type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition, evidence suggests that genetic and environmental factors contribute to the destruction of the beta cells through immune-mediated processes.2,4 Typically, there is an insult that triggers the antigen-presenting cell to present beta self-antigens to the autoreactive T cells. Triggers can be anything from viruses, diet, or factors affecting maternal or intrauterine environment. Over time, the autoreactive T cells fail at self-tolerance of the native B cells and trigger inflammation of the cells, leading to cellular destruction and decreased (and then the absence of) insulin production. Once these beta cells are destroyed, they do not recover, and the patient will become dependent on insulin.5 Once cell destruction begins, symptoms often rapidly follow.

Figure 1. Human Pancreatic Islet Cell |

|

Source: OpenStax College. Exocrine and endocrine pancreas. Published June 19, 2013. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2424_Exocrine_and_Endocrine_Pancreas.jpg CC BY 3.0. |

Type 2 Diabetes

Conversely to type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes typically occurs in adults and is not autoimmune-related. In type 2 diabetes, the body initially still makes some insulin, although it is deficient or is not properly functioning. As the disease progresses, the beta cells may burn out, causing the absence of insulin — although some insulin typically still is produced in this disease.1,2

Other Types of Diabetes

While types 1 and 2 are the classic diseases that many people are familiar with, there are other rare forms of diabetes largely caused by pancreatic dysfunction or late onset of autoimmune diabetes.

Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults

Type 1.5 diabetes, also known as latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA), encompasses characteristics of both type 1 and 2 diabetes. Similar to type 1 diabetes, LADA occurs because of antibodies attacking the beta cells in the pancreas, causing cessation of insulin production. This form of diabetes usually begins in adulthood and generally is diagnosed between 30-50 years of age. LADA usually gradually worsens as the cells are being destroyed. Eventually, insulin production completely stops. This accounts for why many of these patients are erroneously diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, given their age and initial evidence of some insulin production. It is estimated that nearly 4% to 12% of patients who have LADA mistakenly are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes initially. This means that, of the 530 million adults who are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, there are potentially millions of people who may actually have LADA. While this may seem like a technicality, the absence of proper treatment can put these patients in harm’s way, which is why it is important to recognize the differences in pathophysiology.6

Patients who have type 2 diabetes usually start therapy with oral glycemic control and lifestyle modifications. If they are able to maintain a healthy diet, exercise, and strict adherence to their medication regimen, they often do not need injectable insulin — at least not for a significant amount of time after diagnosis. However, patients who have LADA more than likely will require insulin sooner than later in their diagnoses. As discussed, LADA is an autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing cells, similar to type 1 diabetes. Once these cells are destroyed, they can no longer generate insulin. However, in contrast to type 1 diabetes, the destruction of these cells and cessation of insulin usually progresses gradually over weeks to months. Similar to type 2 diabetes, it is recommended that patients with LADA maintain a healthy weight and lifestyle. Environmental and lifestyle factors, such as obesity, have been shown to play a role in progression of the disease. This means the disease initially may be controlled with oral medications prior to definitive treatment with insulin. While this may not seem like an important distinction, given that patients likely will end up using insulin anyway, this significant decrease and eventual cessation of insulin production in LADA can put increased stress on and cause damage to the kidneys. This is why proper identification of diabetes type is important and confers the treatment regimen and timeline.6 LADA shares similarities to types 1 and 2 diabetes in its pathophysiology, symptoms, and treatment. While it may be difficult to distinguish from the other types of diabetes initially, it is important for clinicians to remain vigilant of this disease to ensure patients are getting proper treatment. While emergency medicine providers likely will not be diagnosing LADA in the acute setting, it is important to recognize the differences in pathophysiology and treatment of all types of diabetes.

Type 3C

Another form of diabetes, called type 3C, develops when other diseases affect the pancreas and its ability to function. The disorders that most commonly cause type 3C diabetes include cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis, or a pancreatectomy. The vast majority of cases of type 3C diabetes reported in literature are secondary to chronic pancreatitis. It is estimated that type 3C accounts for 1% to 9% of diabetes cases, although it is theorized that it is commonly misdiagnosed as type 2 diabetes.7

In addition to producing insulin, the pancreas also makes pancreatic enzymes that are transported to and stored in the gallbladder to help with food digestion. The acinar cells are responsible for pancreatic enzyme production, but they cannot produce enzymes if the pancreas is damaged by another disorder or removed altogether. Symptoms likely will include fatty stools, diarrhea, or constipation, and abdominal pain secondary to decreased or absent pancreatic enzyme production.7

This type of diabetes can result in various amounts of insulin production, given that the cells take time to be damaged in some of these conditions. Because of this, patients with this type of diabetes initially may be treated with oral glycemic control medications and eventually transition to insulin injections. In the case of type 3C diabetes because of a pancreatectomy, patients will need insulin injections immediately after surgery — unless it is a partial removal and some of the beta cells in the pancreas are spared.7

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

DKA is a feared complication that can occur for several reasons in patients with diabetes. In patients with diabetes, DKA is the leading cause of mortality in those younger than 24 years of age.1,8 The hallmarks of DKA include hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, and ketosis.8

DKA is an interplay of numerous different physiologic pathways attempting to correct for an insulin deficiency. Within the human body, glucose must be intracellular to be used as an energy source. Insulin acts as a key to the cells and must be present for glucose to enter the cell. In DKA, the absolute or relative insulin deficiency that the body is experiencing causes glucose to be unable to enter the cells and serve as fuel. Because of this, there are a number of downstream effects. Because glucose is stuck extracellularly, hyperglycemia occurs. Because of this insulin deficiency, counterregulatory hormones are released, which are responsible for many of the components of DKA. Catecholamines, growth hormones, glucagon, and cortisol are among the hormones that are released during DKA.1,4,8 The release of these hormones further increases serum glucose and hyperglycemia by promoting glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, lipolysis, and ketogenesis to provide usable energy intracellularly.8 However, the production of these hormones further antagonizes insulin. This results in unopposed glucagon and a resultant metabolic acidosis.1

An anion gap metabolic acidosis occurs in the setting of DKA because the body is producing ketoacids to provide fuel for the body. Ketones are produced by the liver during fatty acid metabolism and serve as fuel for the vital organs, such as the brain, heart, and skeletal muscle tissues, when glucose is unavailable or unusable. This production of ketones is crucial, given that the brain is unable to store fuel and its only energy source is glucose or ketones.8 Ketones are produced when there is no usable glucose available, which can happen during starvation, fasting, intensive exercise, or because of decreased insulin production. This signifies a state of functional starvation, given the body has plenty of glucose extracellularly, although it is unable to use it. In DKA, ketoacids build up within the serum secondary to absolute or relative insulin deficiency, resulting in an anion gap metabolic acidosis.1 During this state of metabolic acidosis, the body’s natural response is to hyperventilate to decrease carbon dioxide. In a state of significant metabolic acidosis, patients may be experiencing Kussmaul respirations as a compensatory mechanism. Kussmaul respirations are characterized by rapid but deep breathing to blow off carbon dioxide.8

While the technical definition of DKA includes an anion gap metabolic acidosis, a patient may display a mildly acidotic or normalized pH if there is concurrent illness causing vomiting or significant volume dehydration. Because of this, clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion when working with these symptoms.1

When a patient is in DKA, their serum glucose is significantly elevated, leading to serum hyperosmolarity and osmotic diuresis. This is because the level of serum glucose filtering through the kidney exceeds the level of renal absorption. When this occurs, significant glucose is spilled over into the urine, otherwise known as glucosuria. Because the kidney is unable to reabsorb more glucose once it has reached its maximum, more water is drawn into the tubules to dilute the urine. This is known as osmotic diuresis and further causes dehydration via free water losses.1,8 Table 1 compares the hallmarks of DKA and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome (HHS).

Table 1. Symptom Comparison of DKA and HHS1,8-10 |

DKA

HHS

|

DKA: diabetic ketoacidosis; HHS: hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome |

Electrolytes in DKA

Another important physiologic process to consider when a patient is in DKA is electrolyte abnormalities, most importantly potassium. In DKA, potassium initially may appear normal or slightly elevated, but this is a misrepresentation.8,9 In DKA, patients have a total body potassium deficit of 3 mEq/kg to 6 mEq/kg. The reason the potassium may look normal to slightly increased is because all of the potassium in the body is extracellular. The potassium shifts extracellularly to replace hydrogen ions within the serum. This is a compensatory mechanism that occurs as patients become acidotic. Because of this, it is very important to identify potassium before starting an insulin drip — because insulin drives potassium intracellularly. Sodium is another element that should be closely monitored throughout episodes of DKA. It often can appear that there is hyponatremia in DKA. However, this is pseudohyponatremia because of the significant amount of glucose within the serum. This is because glucose is hyperosmolar, and water will be drawn into the serum, which results in the sodium dilution. This gives the appearance of hyponatremia, although the sodium likely is normal and will need to be corrected for hyperglycemia. There is a formula that is used to estimate true sodium in the setting of hyperglycemia, taking into account the hyperosmolar effect of glucose:8,9

Corrected sodium = 1.6 × [(Glucose mg/dL - 100) / 100] + measured serum sodium

Serum phosphate levels may be low, although they will appear normal or slightly elevated during episodes of DKA. Similar to potassium, phosphate is shifted extracellularly because of metabolic acidosis and insulin deficiency, which can give the appearance of a normal phosphorus level in the setting of a total body deficit. In addition, osmotic diuresis can further exacerbate phosphate deficit.8 While DKA is significantly more common in type 1 diabetes, it also occurs less frequently in type 2 diabetes. This is because, in type 2 diabetes, there still is insulin resistance that can signify a state of relative insulin deficiency. Thus, in the absence of usable insulin, glucose must remain within the serum, triggering the cascade of ketone body production and the resulting acidosis.

Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Syndrome

HHS typically occurs in adult patients with type 2 diabetes, although it has been increasing in pediatric patients with diabetes. HHS is relatively rare, accounting for 0.8-2 hospital admissions per 1,000.10 While cases of HHS do not comprise a significant amount of hospital admissions, the high fatality rate of 5% to 20% and other negative outcomes demonstrate the importance of recognizing and treating HHS early.1,10

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for HHS regardless of age, given that it can have overlapping features of DKA. In addition, there have been cases reported where patients may display the pathophysiology of both conditions. Early identification and treatment of HHS can decrease lengths of stay and improve patient outcomes. HHS typically has a slower onset than DKA and can take days to weeks to develop. Profound dehydration is characteristic of HHS. In addition, patients will be hyperglycemic and likely will have altered mental status. In contrast with DKA, patients do not have ketosis or acidosis.10

Similar to DKA, HHS is caused by insulin deficiency, although there still is enough insulin within the body to prevent ketone body formation. This is why there is not a ketotic or acidotic state in HHS. Symptoms typically onset more gradually in HHS, which is characteristic of prolonged symptomatic hyperglycemia. In this case, the glucose is hyperosmolar, causing fluid to shift extracellularly to dilute it, resulting in osmotic diuresis. The free water deficit in HHS typically is 1.5 to two times greater than that of DKA and is roughly 3 L to 6 L in most adults. In addition to the significant free water loss, these patients usually report significantly decreased fluid intake at this time, which can further exacerbate the free water deficit. The major physiological problem in HHS that causes symptoms is the significant degree of volume depletion.10

In addition to negative fluid balance, patients in HHS can have significant electrolyte abnormalities because of osmotic diuresis. Electrolyte derangement typically is more significant in HHS than DKA. This is thought to be caused by significant osmotic diuresis, causing decreased renal function for an extended period of time. It also has been documented that hypophosphatemia in HHS patients can contribute to rhabdomyolysis.10

ED Presentation and Evaluation

History

No matter the specific kind of diabetes, patients often will complain of similar symptoms, including polydipsia and polyurea. Presenting to primary care providers with these symptoms often is what triggers testing and diagnosis in adults. Although in pediatrics, diabetes may be difficult for parents to identify because children may be in school and often are thirsty after exertion. This proposes a theory for why many children initially are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when presenting to an ED for symptoms of DKA.

It is important to discover whether a patient has a prior diagnosis of diabetes and, if so, what their current regimen is. If they have an insulin pump or continuous glucose monitor (CGM), it is important to determine how much insulin has been dispensed and what their current blood sugar is on their CGM. Additionally, a point-of-care glucose test should be obtained upon arrival. This will help providers determine whether the patient’s CGM is accurately calibrated. Calculating how much insulin their pump has administered recently as well as what their glucose monitor has been measuring will help providers to determine whether the pump has been administering insulin. It is common in patients, especially children, who have insulin pumps for the site to have failed and inaccurately dispensed medication. It also is important to establish that the patient has been correctly taking their insulin. Medication misuse, either accidental or intentional, is more common in adolescent patients with diabetes who manage their own insulin.1

If the patient presenting to the ED does not have a known history of diabetes but clinical suspicion is high, it still is advised to obtain a point-of-care glucose test immediately. It also is imperative that clinicians ask not only about the symptoms present that day, but also symptoms in the recent days leading up to this presentation. This may help clinicians identify recent illnesses that could be a trigger for this episode. The most common illnesses reported triggering new-onset diabetes in DKA of pediatric patients are gastroenteritis, urinary tract infections, or viral respiratory infections, so clinicians should have a high index of suspicion when patients present with these symptoms.1

Physical Exam

Upon arrival at the ED, providers should perform their usual routine in determining whether the patient is clinically stable. This includes evaluating vital signs for abnormalities. In episodes of DKA or HHS, it is common for patients to have tachycardia and hypotension secondary to severe dehydration. If a patient in DKA presents to the ED and is tachycardic and hypotensive, clinicians should treat this as they would with other hemodynamically unstable pediatric patients, which likely will include fluid boluses. Patients also may present without vital sign abnormalities, although they may appear hypovolemic, which is clinically important for a provider to determine.1

While ensuring a patient is hemodynamically stable, clinicians also should perform the basic airway, breathing, and circulation checks of emergency medicine to evaluate potential reversible causes and other life-threatening etiologies. After ensuring that the patient is clinically stable, providers should perform a thorough physical examination as well as take a thorough history from the patient and/or their caregiver(s).1

When evaluating respirations and breathing, Kussmaul breathing is a clinical hallmark of DKA. As discussed previously, Kussmaul respirations are rapid breaths that patients in DKA will display when carbon dioxide is building up in addition to metabolic acidosis. This is a compensatory mechanism to combat the degree of acidosis. While this is classically taught when discussing DKA, it is not common for children in DKA to display Kussmaul respirations unless the episode is profound.1 Providers also should evaluate hydration status. Key parts of the physical exam that may represent dehydration include delayed capillary refill, mottled skin, and dry mucous membranes.1

It is important to perform an age-appropriate neurologic exam when DKA or HHS is on the differential. This ensures the clinical team has a baseline mental status and exam that can be monitored throughout treatment. Not only can mental status hint at hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, but it also frequently should be monitored by nursing staff throughout treatment to evaluate for cerebral edema, which is a dreaded complication. This is why establishing a baseline mental status upon arrival is crucial for patient safety and treatment.1

In addition to these signs and symptoms, providers sometimes notice the presence of a fruity odor on a patient’s breath when they are in DKA. This is caused by acetoacetate being broken down into acetone. Acetoacetate is a form of ketone body produced during lipolysis.1

In addition to the overall clinical picture and major body systems, clinicians should pay close attention to patients’ other complaints. When pediatric patients are in DKA, they often have nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and lethargy. Because of these nonspecific symptoms, it is best to perform a thorough physical exam, as previously mentioned, which includes an abdominal exam. While it can be difficult to ascertain whether the gastrointestinal symptoms are because of DKA or an intraabdominal pathology, ED providers should use their clinical judgment. For instance, an afebrile child with hyperglycemia and diffuse abdominal pain is more likely experiencing an episode of DKA, although clinicians should keep intraabdominal pathologies on their differential. In contrast to that, a child who is febrile with a leukocytosis, focal abdominal pain, and recurrent emesis should raise a suspicion for acute intraabdominal pathology.1,9

As mentioned, lab work may help providers alter their clinical suspicion for different etiologies. While a significantly elevated or normal white blood cell count may be reassuring to providers, it is not uncommon to see leukocytosis during an episode of DKA.1,11 This is thought to be secondary to counterregulatory hormones, including inflammatory cells that are released during DKA. While blood work or physical exam findings alone may not determine the etiology of a patient’s symptoms, it should be used by clinicians to adjust their differential diagnoses.1

DKA Diagnosis and Management

In a patient presenting to the ED with a history and physical concern for DKA, a provider should obtain numerous laboratory tests and employ treatment to initiate resuscitation. While there have been numerous conditions discussed so far, it is important to remember the pathophysiology behind the disease. This will lead to proper management and disposition of the patient.

The diagnosis of DKA is made based on several laboratory tests that show elevated results for hyperglycemia, acidosis, and ketosis, which are the hallmarks of the disease. Initially, upon arrival, a point-of-care glucose test should be obtained. After this initial check, another glucose test also will appear on the metabolic panel once an intravenous (IV) line is established and bloodwork is sent. Blood glucose (BG) should be tested at least every two hours after arrival.1 It is important to ensure a patient has two functional peripheral IVs when concerned for DKA. This is to ensure reliable access to administer medication or fluids and another site for blood draws.12

BG typically is elevated to more than 350 mg/dL, although many clinicians use BG of more than 200 mg/dL as the technical definition. This level typically decreases once IV fluids are initiated, but the child will remain ketotic and acidotic until insulin is administered. This signifies why the mainstay of treatment for DKA is not lowering glucose but clearing the ketone bodies and resolution of acidotic state. As ketosis and acidosis resolve, the glucose will decrease.12

To assess acidosis, a venous blood gas (VBG) test usually is ordered. VBG will identify the pH of the patient’s blood. The metabolic panel also will list the bicarbonate, which often is below 15 in the setting of anion gap metabolic acidosis. A pH of < 7.3 is consistent with acidosis, although each hospital may have lower pH thresholds for treatment protocols and disposition. In addition, it is important to keep in mind that, if a patient has been severely dehydrated or vomiting, there may be a concomitant contraction alkalosis resulting in a normalized pH.12

Another beneficial laboratory test for diagnosing DKA is the beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) test, which evaluates for ketonemia. A urine sample also may demonstrate ketonuria, although this may provide false reassurance. This is because the BHB, which is the most abundant ketone during initial stages of DKA, is not tested for on urinalysis.1,12,13 This is because the urinalysis uses nitroprusside to assess for ketone bodies, but nitroprusside does not react with BHB.1 Because of this, the urinalysis can be negative or reveal minimal ketones, which provides the previously mentioned false reassurance. This is why it is recommended to test for ketones in the blood with the BHB test. Many hospitals use > 3 mmol/L BHB results as significant for ketonemia.12,13 Research has shown a specificity of 78% to 93% in diagnosing DKA in children presenting to the ED with hyperglycemia when BHB levels are > 1.5 mmol/L.13

A metabolic panel also will reveal electrolyte levels, creatinine, and BUN as markers of kidney function. As previously discussed, it is crucial to know the potassium level prior to initiating an insulin drip. Patients often require potassium replacement before or with insulin. While potassium may appear normal on the metabolic panel, it is important to remember that there is a total body potassium deficit of roughly 3 mEq/kg to 6 mEq/kg in DKA. If insulin is started prior to obtaining and repleting the potassium level, it will drive the extracellular potassium into the cells, further exacerbating the hypokalemia, which can be detrimental.1 Additionally, an electrocardiogram should be obtained if the potassium level is abnormal.9

Other blood work that should be considered are phosphorus and magnesium levels, a complete blood count, and a pregnancy test, if the patient is female. Clinicians also should investigate the other symptoms that patients may present with, such as liver function or lipase tests if patients present with focal abdominal pain.12 Many hospitals and EDs have order sets that contain these regimens for when DKA is suspected. Studies have revealed that using the hospital-protocolized DKA order set decreases the time to resolution of DKA and subsequently reduces complications and length of hospital stay.13,14

Table 2 outlines the diagnostic criteria for DKA.

Table 2. Diagnostic Criteria of Diabetic Ketoacidosis12,13 |

Hyperglycemia

Ketosis

Metabolic Gap Acidosis

|

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Treatment

As discussed, patient stabilization is the priority in every patient who enters the ED. After stabilization, taking a patient history, conducting a physical examination, and obtaining laboratory tests can help providers reach a diagnosis of DKA. The primary goal of treatment for DKA involves closing the anion gap metabolic acidosis and preventing ketone body production, which is done via insulin. While this is the most important goal, there are many other objectives that need to be accomplished, such as correcting the negative fluid deficit, electrolyte replacement, and treatment of precipitating events. Identification and treatment of precipitating events is crucial because the underlying problem is the frequent cause of death in pediatric patients presenting in DKA.

Fluids

Initial therapy for DKA includes fluids. Typically, there is a delay in insulin therapy initiation, given that it takes time for the potassium level to result. During this time, fluid management is important. Pediatric patients in DKA often are down 5% to 10% of their body weight.1,9 There is some debate among experts regarding how fluid should be replaced and at what rate. This is because of the risk of cerebral edema, which is a reported complication in treatment of DKA, specifically in pediatric patients.1 This is why most institutional protocols attempt fluid resuscitation over 24 to 48 hours from presentation — to avoid fluid overload or other complications. Similar to fluid resuscitation in burn management, many protocols involve replacing the first half of a patient’s free water deficit in the first eight hours and the second half during the following 16-24 hours.1,9

It also is crucial to treat the patient based on their needs. If a patient presents to the ED in DKA and is in shock (according to their vital signs), the clinician should order a 20 mL/kg normal saline (NS) bolus. This should be repeated if the patient continues to display signs or symptoms of hemodynamic instability. After the patient is hemodynamically stable, providers should switch to a maintenance fluid order. There are different ways that IV fluids (IVFs) can be initiated in the treatment of DKA. Some experts recommend the use of two-bag systems, and some replete fluids in a stepwise fashion. While many hospitals have institutional protocols regarding this, there is not yet a standard of care when it comes to fluid resuscitation in DKA.

Some providers initiate fluids one at a time for fluid resuscitation. This can include NS at 1.5 times the maintenance rate. This usually is done with 0.9% NS, although some experts now recommend a 0.66% sodium chloride solution. However, this is not readily available at many institutions, given that it needs to be compounded by the pharmacy.1 If repleting fluid this way with a single bag of NS at a time, dextrose will need to be added to the fluids when BG is under 200 mg/dL to 250 mg/dL. This may seem counterintuitive, but BG typically drops much more rapidly than the anion gap closes. It is essential that the insulin drip is not turned off prior to acidosis resolving, which is why sugar often must be added to the fluids to prevent hypoglycemia in the setting of ongoing insulin use. This method has the added benefit of less rate adjustments and calculated ratios, when compared to the two-bag system.1

Two-Bag Fluid Method

Many providers and experts are now advocating for the two-bag method when treating DKA. This is an approach that uses two separate bags of IVF that are running simultaneously and at different proportions based on the patient’s current BG levels. This approach involves one bag of IVF with dextrose and one without. The fluids will collectively run at 1.5 times the maintenance IVF rate to avoid fluid overload. Typically, clinicians use 0.9% NS with 40 mEq/L of potassium added and a bag of dextrose 10%. Once the fluids are running at 1.5 times the maintenance rate, insulin infusion can be started. The proportions in each of the bags are readjusted based on the patient’s BG levels, always ensuring that the total fluid rate stays at 1.5 times the maintenance rate for that child. For instance, if the BG level is more than 350 mg/dL, then 100% of the administered fluids should be coming from the saline bag alone. This means that, as the BG is downtrending, the rate of dextrose-containing fluids being administered will increase to maintain safe BG levels while insulin is ongoing.9,11

For example, say a 6-year-old female weighing 20 kg presents to the ED in DKA. She is diagnosed with new-onset type 1 diabetes. Her BG initially is 470 mg/dL. Here is how to calculate the two-bag method for her based on her initial BG.

Using the 4-2-1 rule: 4 mL/kg/h for the first 10 kg, 2 mL/kg/h for the next 10 kg, 1 mL/kg/h for additional weight above the 20 kg already accounted for. Add these amounts and divide by 24 to get the hourly maintenance rate.

Multiply 60 mL/h by 1.5 to get 90 mL/h, which is the target 1.5 times maintenance IVF rate.

20-kg child: (4 mL/kg/h × 10 kg) + (2 mL/kg/h × 10 kg) = 60 mL/h

In the two-bag system, if BG currently is 470 mg/dL (> 350mg/dL), then 100% of fluids should be coming from the saline bag and not the dextrose-containing bag.

Once her BG is 315 mg/dL, the saline bag should be running at 75% of its total fluid rate, and the dextrose bag should be increased to run at 25% the total fluid rate. Because dextrose 10% is being used at 25% the total fluid rate, the patient is receiving the equivalent of 1.5% dextrose.

Using the two-bag system allows for closer glycemic control throughout treatment. This helps to avoid hypoglycemia and premature cessation of the insulin drip. There often is a tendency to lower or stop the insulin drip when BG drops below 200 mg/dL to 250 mg/dL when using the one-bag method.

Table 3 outlines treatment plans for DKA.

Table 3. DKA Treatment1,9-13 |

Insulin

Fluids

Potassium Repletion

|

DKA: diabetic ketoacidosis; NS: normal saline; D10: dextrose 10%; BG: blood glucose; K: potassium |

Cerebral Edema

Cerebral edema is a rare, feared complication of DKA. The literature reports cerebral edema as occurring in up to 1% of patients being treated for DKA.3,8 This is thought to be caused by the rapid shifts in osmolality that occur with treatment.1,8,10-12 These rapid shifts in fluids are thought to cause cerebral hypoperfusion and ischemia secondary to prolonged acidosis.12 While the occurrence of cerebral edema is low, the mortality rate is roughly 25%, which is why this is such a feared complication. Children who experience cerebral edema in the setting of DKA treatment and survive often have significant neurologic abnormalities as a result.8 Risk factors that are associated with increased risk of cerebral edema secondary to DKA treatment include severe acidosis or dehydration, age younger than 3 years, pH < 7.0, failure of sodium to correct despite fluid resuscitation, and elevated kidney function.1,8,11,12

It was initially hypothesized that this was occurring because of the rapid infusion of large amounts of fluids, but the incidence has persisted despite stricter protocols and standards of care that aim to restrict initial fluid administration in DKA.15 In addition, a case-control study evaluated 61 cases and 355 controls that did not reveal any association between the rate of fluid administration and development of cerebral edema.9 The only modifiable risk factor in this study was the use of sodium bicarbonate. Many experts and studies argue against the administration of sodium bicarbonate in DKA management.1,9

There are many signs that a patient may be experiencing cerebral edema that are all secondary to increased intracranial pressure. This includes headache, irritability, agitation, bradycardia, hypertension, papilledema, and altered mental status. This is why it is essential to get a baseline neurologic exam upon patient arrival at the ED prior to initiating treatment. The provider and nursing staff should be aligned about the patient’s neurological status so that they can readily detect any changes that may occur during treatment.1,8

Cerebral edema can occur up to 48 hours after initiation of DKA treatment, although it most frequently occurs between three and 12 hours.12

As mentioned, bolusing insulin in DKA prior to initiating an insulin drip is thought to increase the risk of cerebral edema. Given this increased risk and lack of evidence supporting its benefit in comparison to an insulin drip, insulin boluses are not recommended prior to insulin infusion during the treatment of DKA.1,8

It is crucial for providers to know how to treat cerebral edema so that it can be addressed if necessary. If clinicians have a high index of suspicion for cerebral edema, the mainstays of treatment are mannitol and hypertonic saline. Mannitol is an osmotic diuretic that will draw water from the brain tissue and into the vessels. It can be administered as IV 0.5 g/kg to 1 g/kg over 15 minutes. Hypertonic saline is 3% saline, which can be administered at 2.5 mL/kg over 30 minutes.8 Clinicians also should elevate the head of the bed and consult neurosurgery.12 While it may be recommended to obtain a computed tomography head scan if the patient is stable enough to undergo it, the diagnosis of cerebral edema is clinical.9

Potassium Repletion

As discussed, in episodes of DKA, potassium usually appears normal or slightly elevated, which is an inaccurate representation the patient’s potassium status. It is important that clinicians replete potassium based on institutional protocol prior to insulin administration. The general rule for potassium repletion is that if potassium is 3.5 mEq/L to 5.5 mEq/L, 30 mEq/L of potassium should be given. If potassium is 1.5 mEq/L to 3.5 mEq/L, 40 mEq/L of potassium should be supplemented. To replete this, it can be administered as half potassium phosphorus and the other half potassium chloride or acetate.1

Insulin

Insulin should be started at 0.1 U/kg/h and should not be bolused because of the increased risk of cerebral edema, exacerbation of electrolyte imbalances, and potential for hypoglycemia.1,9,11 It is a drip that will stay at this fixed rate regardless of BG level — with a couple of exceptions. The insulin drip can be started once a patient is hemodynamically stable. For instance, if the patient is hypotensive and receiving fluid boluses, the insulin should not be given until the patient is resuscitated. If a patient in DKA is hemodynamically stable and does not require fluid boluses, the insulin drip can be started at the same time as the maintenance fluids. However, as mentioned, it is important for providers to know and replete the potassium before administering insulin. Because lab results do not come back instantaneously, providers often start fluids prior to labs resulting. Therefore, patients often will be on fluids before potassium is repleted.1

If a clinician decides to follow the two-bag protocol, 40 mEq/L potassium often is added to the bag of NS prior to potassium levels resulting. This allows fluids, potassium repletion, and insulin to be administered more readily.9 The goal of the insulin drip on glucose is that it will drop BG by roughly 50 mg/dL/h to 100 mg/dL/h. Dropping the BG in this controlled setting helps to prevent significant intracerebral osmolar shifts. It is important for continued and frequent monitoring of BG once the insulin drip is started. As mentioned, if using a single bag of fluid resuscitation, dextrose should be added to fluids once BG is < 200 mg/dL to 250 mg/dL. When using the two-bag system, glucose is being monitored frequently, and the proportion of dextrose in the total fluid rate is being adjusted to meet these needs.

While patients on insulin drips often are admitted for further monitoring and management of their inciting event, an ED provider may be responsible for transitioning a patient from an insulin drip to subcutaneous insulin. When determining when the insulin drip can be discontinued, there are many details that need to be considered. It is imperative that the insulin drip is not stopped suddenly prior to the anion gap closing. Insulin is what reverses ketosis and is the only definitive treatment for DKA. When the anion gap has closed and the patient is no longer ketotic, subcutaneous insulin should be administered while the patient is receiving the insulin drip. This may feel uncomfortable to providers and nursing staff for fear that the subcutaneous and infusion of insulin would lower BG too rapidly, causing a hypoglycemic event. However, it is essential that the insulin infusion be continued for one to two hours after the first dose of regular insulin subcutaneously. This is because of the half-life and time-to-onset of the different kinds of insulin. If the insulin drip is stopped prior to the subcutaneous injection, the child likely will begin to form ketones again.11

In patients presenting in mild DKA, an insulin drip may be unnecessary. Many clinicians will try to rehydrate and close the anion gap in the ED for children who present in mild DKA. A study evaluated the use of lispro subcutaneous injections 0.15 U/kg every two hours in comparison to IV insulin at 0.1 U/kg/h in the setting of mild DKA. This study revealed no significant differences between the two groups, with the benefit that the subcutaneous injections can be adjusted more easily to maintain BG.11

While a patient in mild DKA may be treated and discharged from the ED, it is important that the patient’s clinical picture is accounted for. A patient’s numbers may not be very impressive, but if they are unable to tolerate fluids by mouth, they may require admission secondary to the triggering event for further management. When this occurs, they often can be admitted to the pediatric floor because they will not have an insulin infusion.11

Many pediatric patients who regularly follow up with their endocrinologist will have a “sick day protocol” that may be used. This is a treatment plan letter that may be available in a patient’s chart that outlines the insulin regimen that they should use when they are experiencing illnesses. This is a way for patients and caregivers to rapidly identify increased insulin needs and address them at home in mild scenarios. These treatment plans typically contain goal BG levels, additional insulin adjustments that can be made, and instructions on when it may be necessary to seek care.11 If a patient has a sick day protocol, providers should locate that within their chart and find any instructions that their endocrinologist is comfortable with if the patient is to be discharged. This treatment plan and patients with close follow-up can serve as reassurance for discharge in the setting of mild DKA and improvement after treatment.11,16

Euglycemic DKA

Euglycemic DKA is more common in adults, although there have been cases reported in children. While the technical definition of DKA includes hyperglycemia, there are cases (e.g., euglycemic DKA) where patients can be in DKA but have relatively normal BG levels.13 When this is seen in children, it typically is because they are well-hydrated and have a relative insulin deficiency in the setting of an illness. They often have been taking their daily regimen, but in the setting of an illness, their body is requiring more, making it a relative deficiency to their current needs. While it may be tempting to see a normal or low glucose and think the patient may not need insulin, providers should stay vigilant when there is acidosis or ketosis. If a patient presents in euglycemic DKA, fluids containing dextrose should be initiated as well as the insulin drip. As peviously discussed, the only way to reverse ketoacidosis is using insulin. Therefore, if a child is presenting with signs or symptoms of DKA, it is important to check the laboratory results, even if their glucose is slightly elevated or normal.1

HHS Diagnosis

The work-up for HHS typically is similar to that of DKA — checking BG, plasma ketones, VBG, and serum osmolality. Typically, in HHS, the BG is elevated more than often is seen in DKA. In HHS, it is typical to see BG greater than 600 mg/dL. A normal serum osmolality ranges from 275 mOsmol/kg to 300 mOsmol/kg, but it often is greater than 330 mOsmol/kg in HHS. When evaluating VBG in a patient with HHS, their pH should be greater than 7.25-7.3 because the pathophysiology of HHS does not include ketoacidosis (like in DKA). Because of this, the serum ketones should be minimal or negative. In HHS, serum ketones up to 1.5 mmol/L are acceptable because the patient may be in a state of starvation ketosis, which would account for some production of ketones. Taking these laboratory values into account, it is apparent that HHS typically is diagnosed in patients with significantly elevated BG and elevated serum osmolalities in the absence of ketone production.10

HHS Treatment

In HHS, the primary targeted intervention is fluid resuscitation. As mentioned, the typical fluid deficit in HHS can be double that in DKA, totaling up to 6 L in adults. This is why it is crucial to begin fluid resuscitation when HHS is suspected if patients do not have other medical comorbidities that would preclude it. The typical goal of fluid resuscitation can vary between different hospital systems, but, in general, the goal is to replace this total body fluid deficit within 24 hours.10

Fluid usually is replaced with NS at an initial rate of 20 mL/kg, which often is repeated after the initial bolus. It is important to evaluate the patient after administering fluid boluses to ensure they are tolerating the fluids well. If patients have comorbidities, such as heart failure, it is important to know their estimated ejection fraction and ensure they are not being overloaded with the fluid boluses. This may mean that fluids will be administered more slowly.10

It is important to regularly check BG — fluid administration typically significantly decreases serum glucose in HHS because of the hemodilutional effect as well as the improvement in perfusion. Because of that, insulin does not always need to be administered in patients in HHS. Because HHS is not a ketotic state, insulin is not always necessary or recommended for acute management. Many HHS cases are type 2 diabetic patients who are insulin-naive and may be more sensitive to insulin administration. This is why the goal in HHS treatment is identification and treatment of the precipitating event(s) as well as fluid resuscitation.10

Patient Disposition

Not all patients who present to the ED in DKA need to be admitted to the hospital. If a patient presents to the hospital in DKA with new-onset diabetes, most facilities recommend admission for education and establishment of an insulin regimen with the patient and caregivers. Patients who present in mild DKA, are successfully rehydrated, and are tolerating oral intake can arrange close follow-up with their primary care provider. If caregivers are comfortable with continuing treatment and management at home, patients can be considered for discharge directly from the ED. Patients who require an insulin infusion will require admission to the hospital.

It is important for ED physicians to know the policies and protocols of the institutions they work in. Many places require patients receiving an insulin infusion to go to the intensive care unit (ICU). However, not all patients who are started on an insulin drip in the ED need to continue the infusion. Some patients can be transitioned to subcutaneous insulin while still in the ED in less severe cases. There are some indicators and blood levels that, if present, likely indicate an ICU admission. Low pH or bicarbonate are two such signs. Most protocols will recommend ICU admission if the pH on arrival is 7.2 or less.8,9,15 If the bicarbonate is < 5, this is another indicator that the patient likely will need admission to the ICU.9,15 In addition, patients who have significant electrolyte abnormalities or altered mental status will require admission to the ICU.

Hypoglycemia

While diabetes treatment and management generally attempt to treat hyperglycemia, it is equally as important to know how to recognize and treat hypoglycemia, since it quickly can become fatal. Hypoglycemia adds a psychological challenge to diabetic patients that makes a disease that is already difficult to control in children even harder.17-19 Many patients and caregivers of people with type 1 diabetes report significant emotional distress and challenges that come from trying to maintain tight glycemic control.17,19 While hypoglycemia can be very frightening, patients and caregivers should be encouraged by recently published decreased rates of hypoglycemia since CGMs and insulin pumps were implemented.19,20

While many hospital systems use a numerical cutoff for BG, a hypoglycemic event is classified as any BG that is low enough to cause symptoms of hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemic events include a spectrum of symptoms — from shakiness and diaphoresis to impaired brain function and coma. These symptoms are secondary to adrenergic stimulation, and the lack of glucose getting to the brain can cause altered mental status or difficulty concentrating. While these symptoms are common in all age groups when hypoglycemia is present, excessive irritability or tantrums in very young children also should be a red flag to caregivers and indicate that a BG check is necessary.17,19-22 Many children with type 1 diabetes will wear a CGM that continuously tracks their BG, but if a child is experiencing signs or symptoms of hypoglycemia, the BG needs to be checked with a meter to ensure the accuracy of the device. In addition, the devices may lag by 15 minutes, which is a crucial time to treat low blood sugar before it becomes detrimental.17

Most hospitals use a BG cut-off level of 70 mg/dL in patients with a history of diabetes, which helps to initiate interventions based on the hospital-based protocol if a patient is below this level or experiences symptoms.17,20 It is recommended that children with type 1 diabetes spend less than 4% of their lifetime at a BG of less than 70 mg/dL.17,19-22

Providers should obtain a thorough history from caregivers to determine how much glucose has been administered and in what form after a child presents to the ED following a hypoglycemic event. Severe hypoglycemia is classified as a low blood sugar event in which the patient is neurologically altered and unable to self-administer medications or forms of glucose.17 Symptoms associated with severe hypoglycemia can be anything from mild confusion to seizures.19,20 When severe hypoglycemic events occur, it is important for their endocrinologist to be consulted. Patients should discuss triggers and if medication regimens need to be adjusted, especially in the setting of recurrent events. It also is extremely important for patients to notify their provider if they have hypoglycemic events without symptoms because that is very concerning and may require a shift in their BG goal range.17,23 Common reasons for hypoglycemic events include excessive insulin administration, exercise, sleep, skipped meals (or not completing food that was accounted for in carbohydrate count), and alcohol use in adolescents.17,18,22

Hypoglycemia Treatment

Hypoglycemia treatment is an essential part of diabetes education. Caregivers and patients should be extremely comfortable with recognition and management. It is important to keep in mind that, when children are very active, it often can trigger hypoglycemia, which is why glucose should be monitored closely before, during, and after exercise.17

When in a hypoglycemic state, patients should be treated with oral glucose first if they are conscious and able to swallow. It is recommended that patients with type 1 diabetes always have sources of glucose, such as candy, peanut butter, juice, or gummies, with them. These are forms of rapid-acting glucose that should help to readily improve BG. When instructing families to carry glucose sources with them, it is recommended that the source raise BG by 54 mg/dL to 71 mg/dL. This is roughly 0.3 g/kg oral glucose.17 In most children other than infants, administering 15 g of carbohydrates to a conscious child, which is roughly 4 fluid ounces of juice, four glucose tablets, or a tube of glucose gel, is acceptable.20

Depending on the cause of the hypoglycemic event, patients may require more carbohydrates after their rapid glucose source. For instance, hypoglycemia caused by excessive insulin will require identification of the amount of insulin administered to determine how long that will be in their system and affect their BG. During this time, it may be necessary for patients to suspend their insulin pump temporarily until their BG stabilizes. After the initial hypoglycemic event and treatment, BG should be checked every 15 minutes until it remains stable and above the target glucose level.17,20,21

In the setting of severe hypoglycemia outside of a healthcare setting, patients and caregivers are prescribed and instructed to administer glucagon. Glucagon can be administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly. In children weighing less than 25 kg, 0.5 mg of glucagon can be used. If a child weighs more than 25 kg, caregivers should administer 1 mg of glucagon.17,19,20 There also are new data and studies looking into intranasal glucagon administration for children. Currently, there is a formulation of intranasal glucose on the market that is a single 3-mg dose that can be used for children older than 4 years of age.17

If a patient is in the hospital when they experience a hypoglycemic event, dextrose (typically as 10% dextrose) should be given at a rate of 2.5 mL/kg to 5 mL/kg, which is roughly 0.25 g/kg to 0.5 g/kg of dextrose.17,19,20 Different concentrations of dextrose usually are administered to different age groups:20

- Patients aged younger than 1 year: 10% dextrose at 5 mL/kg to 10 mL/kg.

- Patients aged 1 to 8 years: 25% dextrose at 2 mL/kg to 4 mL/kg.

- Patients aged 8+ years: 50% dextrose at 1 mL/kg to 2 mL/kg.

For instance, infants are given 10% dextrose because of the risk of vascular injury that comes with infusing higher concentrations, such as 50% dextrose, which can be used in teens and adults.20

If patients remain persistently hypoglycemic despite these interventions, the next step is to initiate a dextrose infusion. Typically, this is done with dextrose 10% at 1.5 times the maintenance rate.20,21

Conclusion

It always is important to keep diabetes on the differential diagnosis when patients are presenting to the ED. Diabetes and DKA sometimes can present with common symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, increased urination, irritability, and fatigue. These symptoms are seen regularly in pediatric ED complaints, which is why providers must be vigilant when evaluating pediatric patients. DKA most commonly occurs in type 1 diabetes, and patients often present to the ED for symptoms secondary to DKA with new-onset diabetes mellitus. In DKA, patients typically have hyperglycemia, ketosis, and an anion gap metabolic acidosis, which are the mainstays of diagnosis. It is important to identify triggers of DKA in patients with previously established type 1 diabetes because the root cause often can lead to ongoing symptoms and the potential for recurrent DKA. In DKA, insulin is crucial to resolve the state of ketosis. Depending on the severity of DKA, patients may be treated successfully, and the anion gap closed, with insulin injections, although many patients will require an insulin infusion.

It also is important to evaluate for type 2 diabetes in the pediatric population because the incidence has increased. Additionally, it is important to recognize signs and symptoms of HHS because it can occur in pediatric patients — although it is rare. The key difference between DKA and HHS is that HHS is not a state of ketosis; therefore, the insulin infusion is not as essential to treatment as fluid resuscitation.

Hypoglycemia also is a major concern — and an area where extensive education for the patients and caregivers is essential to avoid or limit potentially fatal complications. Hypoglycemia in children typically occurs secondary to illness and poor oral intake, excess insulin administration, or increased activity. It is crucial for patients to always have a BG meter and numerous forms of glucose with them at all times in case they experience hypoglycemia. Patients likely also will have glucagon prescribed to them, which should be used as an injection if a patient is not in a healthcare setting and is unresponsive or unable to reliably swallow.

Courtney Botkin, DO, is Resident Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Daniel Migliaccio, MD, FPD, FAAEM, is Clinical Associate Professor, Director of Emergency Ultrasound, Ultrasound Fellowship Director, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

References

- Vella AE. Diabetes in children. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma OJ, Yealy D, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine. 9th ed. McGraw Hill;2020:971-975.

- Diabetes U.K. Differences between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/diabetes-the-basics/differences-between-type-1-and-type-2-diabetes

- Hadley SM, Michelson KA. Delayed diagnosis of new onset pediatric diabetes leading to diabetic ketoacidosis: A retrospective cohort study. Diagnosis (Berl). 2024;11(4):416-421.

- Younis M, Ayed A, Batran A, et al. The outcomes of implementing clinical guidelines to manage pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis in emergency department. J Pediatr Nurs. 2025;81:63-67.

- Los E, Wilt AS. Type 1 diabetes in children. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Updated June 26, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441918/

- Cleveland Clinic. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA)? Reviewed Oct. 14, 2024. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/lada-diabetes

- Cleveland Clinic. Type 3C diabetes. Reviewed May 8, 2023. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24953-type-3c-diabetes

- EL-Mohandes N, Yee G, Bhutta BS, et al. Pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Updated Aug 21, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470282/

- Tzimenatos L, Nigrovic LE. Managing diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78(3):340-345.

- Zahran NA, Jadidi S. Pediatric hyperglycemic hyperosmolar syndrome: A comprehensive approach to diagnosis, management, and complications utilizing novel summarizing acronyms. Children (Basel). 2023;10(11):1773.

- Rosenbloom AL. The management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Diabetes Ther. 2010;1(2):103-120.

- Lord K, Jacobstein C, Sharer G, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) clinical pathway — Emergency department, ICU, and inpatient. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Published June 2006. https://www.chop.edu/clinical-pathway/diabetes-type1-with-dka-clinical-pathway

- Helman A, Baimel M, Sommer L, Tillmann B. Episode 146 – DKA recognition and ED management. Emergency Medicine Cases. Published September 2020. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/dka-recognition-ed-management

- Tenedero C, Soliman A, Samaan MC, Kam AJ. Safety audits in the emergency department: Applying the threat and error model to the management of pediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(12):e1637-e1641.

- Gripp KE, Trottier ED, Thakore S, et al. Current recommendations for management of paediatric diabetic ketoacidosis. Paediatr Child Health. 2023;28(2):128-138.

- Deeb A, Yousef H, Abdelrahman L, et al. Implementation of a diabetes educator care model to reduce paediatric admission for diabetic ketoacidosis. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:3917806.

- Abraham MB, Karges B, Dovc K, et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Assessment and management of hypoglycemia in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2022;23(8):1322-1340.

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; 14. Children and Adolescents: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes — 2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl 1):S208-S231.

- Ly TT, Maahs DM, Rewers A, et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines — Hypoglycemia: Assessment and management of hypoglycemia in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2014:15(Suppl 20):S180-S192.

- Banh K, Tsukamaki J. Hypoglycemia. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Updated 2024. https://www.saem.org/about-saem/academies-interest-groups-affiliates2/cdem/for-students/online-education/peds-em-curriculum/endocrine/hypoglycemia

- Le L. Pediatric Small Talk — Pour some sugar on me: Pediatric hypoglycemia. emDocs, Published Feb. 2, 2022. https://www.emdocs.net/pediatric-small-talk-pour-some-sugar-on-me-pediatric-hypoglycemia/

- Massachusetts General Hospital. Treating hypoglycemia and type 1 diabetes. Published July 12, 2019. https://www.massgeneral.org/children/hypoglycemia

- Urbano F, Farella I, Brunetti G, Faienza MF. Pediatric type 1 diabetes: Mechanisms and impact of technologies on comorbidities and life expectancy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(15):11980.