Emerging Ethical Dilemmas with Deep Brain Stimulation

June 1, 2025

By Stacey Kusterbeck

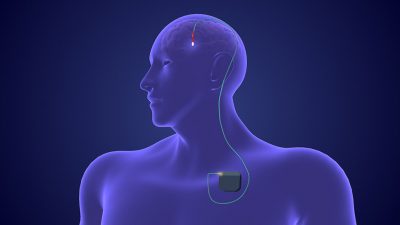

For decades, deep brain stimulation (DBS) devices have been used to treat neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders, with an estimated 263,000 deep brain stimulation devices currently implanted.1 However, there are some ongoing — and emerging — ethical concerns with this technology.

Informed consent. “Ensuring informed consent requires transparent communication about potential contraindications and limitations of DBS, particularly when media portrayals of the benefits of DBS may generate unrealistic expectations,” warns Lauren Sankary, JD, MA, HEC-C, an assistant professor of neuroethics in the Department of Neurological Surgery at University of Texas Southwestern and a clinical ethicist at William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital in Dallas.

For example, portrayals of DBS on YouTube and other platforms might suggest DBS will cure or prevent the progression of Parkinson’s disease or will alleviate all motor symptoms immediately. In reality, DBS may only address a subset of motor symptoms after approximately six months of programming.

In informed consent conversations, clinicians must weigh the potential benefits of DBS against the potential risks. Risks include surgical complications or side effects affecting cognition, behavior, and mood, notes Sankary. Clinicians need to explore patients’ goals to clarify whether DBS is likely to provide benefits that are consistent with the patient’s expectations. For instance, if a patient is bothered by gait, speech, and swallowing issues caused by Parkinson’s disease that DBS does not target, and the patient has minimal tremor or dyskinesia, then the benefits of DBS may not justify the burdens and risks of undergoing DBS for that particular patient.

“It is important to provide information about alternative treatment options a patient may wish to consider instead of, or prior to, undergoing DBS,” says Sankary.

Clinicians should confirm that patients understand the limitations of what DBS can offer. “As a clinical ethicist, I am also attentive to whether patients and their loved ones have an opportunity to think through longer-term considerations,” says Sankary. These considerations include device programming needed to optimize stimulation settings, battery replacements that may become necessary, and plans for surrogate decision-making if a patient loses capacity.

“A multidisciplinary approach, involving consultation with palliative medicine, social work, or a clinical ethicist, may be helpful to support advance care planning and consideration of longer-term priorities for symptom management,” says Sankary.

There also is a concern about whether people really are voluntarily consenting to adaptive DBS. “It is a last-resort technology, and people might indeed be desperate. There might be some people who say that they are actually being manipulated by their disease,” says John D. Banja, PhD, a medical ethicist at the Center for Ethics at Emory University. To mitigate this possibility, clinicians typically ensure that patients have exhausted all other possible remedies before recommending DBS.

Data privacy and security. “Typically, these kinds of syndromes are stigmatizing. Remember that these recent models record your brain patterns. That immediately raises an issue — now I have data on your brain states. And there is a need to secure and protect [those] data, because most people would regard it as exquisitely private,” says Banja.

Clinicians and researchers likely will face questions from patients and study participants about what precautions were taken to prevent hackers from breaking into the system and harming individual patients. “Companies will need to persuade us that it’s safe, and that data will be well-protected and only shared with clinicians who have a right and a need to know. And are the current de-identification of data protocols good enough, or can somebody still figure out who the patient is? The literature I read suggests that absolute anonymity can no longer be guaranteed,” says Banja.

When reviewing DBS study protocols, Sankary says that Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) should consider these factors:

- the risk-benefit ratio of the proposed research, with attention to surgical risks at the time of DBS implantation, battery replacement, and explant, as well as short- and long-term risks related to stimulation;

- the justification for inclusion and exclusion criteria;

- the adequacy of safeguards for informed consent.

“Furthermore, IRBs should assess the appropriateness of plans for device explant or post-trial access to the device and follow-up care that may be needed after the study concludes,” says Sankary.

With adaptive DBS, recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for Parkinson’s disease, stimulation can be adjusted in real time based on the patient’s brain signals.2 Devices are externally controlled, allowing healthcare providers to adjust the system as needed if a seizure is coming on or a tremor episode is starting. “You’ve got this device that is controlling the brain, independent from you. You’re messing with a person’s brain, the most intimate part of us — a person’s mind and identity and personality, and how they understand the world. This is a kind of contemporary take on ‘Big Brother watching you’ and even controlling you,” says Banja.

“As with all new technologies, this is going to be an iterative process. We will have some bad outcomes, and we’re going to learn from our mistakes. Right now, we are in the infancy. Hopefully, the technology will only continue to improve,” says Banja. Hospital-based ethicists can help to address these ethically complex issues at their institutions by participating in IRBs. “The interesting question is, do we need to train a new cadre of ethicists who specialize in these technologies, especially AI (artificial intelligence)?” asks Banja.

Adaptive DBS raises some new ethical questions about data privacy and security. “This is due to the capacity of these systems to record and store sensitive neural data,” says Sankary. There are also some unique ethical concerns about patient autonomy and control. “Stimulation parameters adjust automatically, sometimes below the threshold of a patient’s conscious awareness and without clinician oversight,” explains Sankary.

Researchers investigating novel applications of DBS face these unique ethical issues with study design, says Sankary:

- Establishing appropriate controls. The elaborateness of DBS as an intervention increases the expected placebo response. “Researchers can use sham stimulation with a washout period after device implantation in a masked crossover study design, given ethical contraindications to sham surgery as a traditional placebo control,” offers Sankary.

- Needing to evaluate both the short- and long-term effects of DBS. “It is important to evaluate alignment between academic and industry-based research priorities, and the priorities of patients and caregivers,” adds Sankary.

Researchers also face evolving ethical concerns with the expansion of DBS use for other conditions (such as depression, schizophrenia, or Alzheimer’s disease), where the evidence still is not sufficient. “This is a key ethical dilemma that my lab has worked on,” reports Laura Cabrera, PhD, an associate professor in engineering science and mechanics, a senior research associate at the Rock Ethics Institute, and the Dorothy Foehr Huck and J. Lloyd Huck chair in neuroethics at Pennsylvania State University (PSU).

The neuroethics lab at PSU engages with diverse topics around neurotechnology, with a focus on neuromodulation interventions. “For the past several years, we have seen a desire to find interventions that can help people. But there is also hype and false promises. This makes an already desperate group of individuals even more vulnerable,” says Cabrera.

One example is the use of DBS in psychiatric disorders. Currently, DBS is not approved for most psychiatric disorders, but several clinical trials are ongoing. Obsessive-compulsive disorder is the only condition with a humanitarian device exemption, that allows people to get the intervention outside of a clinical trial.

Even in established applications, such as for Parkinson’s disease, new ethical questions are emerging. There is a shift toward offering DBS to patients at earlier stages, which affects the risk/benefit analysis. The longer someone lives with an implant, the more risks for complications there are, the greater the chance of need for battery replacements there is, and the greater the chance there is of more severe nonmotor symptoms that most patients would not have lived to experience before DBS was common practice. “Thus, a key ethical concern is when is the best time to start this therapy, and how best to assess the benefits and risks of starting earlier vs. delaying its use,” says Cabrera.

Patients have many misperceptions about DBS — for example, that it will cure Parkinson’s disease or that it represents a form of mind control. “Clinical ethicists could help physicians to determine if misperceptions rise to a level such that they compromise a patient’s decision-making capacity,” says Hillary King, PhD, MA, a postdoctoral research scholar in neuroethics at PSU. This will help to ensure that patients who consent to DBS have the capacity to do so, and that patients who have capacity are not unjustly denied the opportunity to consent.

At many hospitals with DBS programs, a multidisciplinary group of physicians meet regularly to discuss patients who recently have gone through a candidacy assessment process. The group determines whether those patients are candidates for DBS, based on both medical and nonmedical factors (such as social or psychological factors). “Having a clinical ethicist participate in those discussions — at least in some cases, such as when there are questions about a patient’s decisional capacity — could potentially be beneficial,” says King.

King says that clinicians should consider requesting an ethics consult in these situations:

- when there are questions about a patient’s capacity to consent to DBS surgery, a battery replacement surgery, or ongoing stimulation;

- when there are disagreements over appropriate goals of care;

- when there are questions about whether DBS stimulation is affecting the patient’s autonomy (such as in the case of stimulation-induced impulsivity).

Ethicists also can help to address the unique challenges to meeting the ethical standards of informed consent, given the complexity of DBS technology and the myriad decisions involved in its implantation. For example, clinicians must make decisions on the target brain region, the device manufacturer, using rechargeable vs. chargeable batteries, and how to address the ongoing maintenance DBS requires for programming updates and battery changes. “Clinical ethicists can work alongside clinicians to implement procedures or policies to mitigate those challenges,” says King.

References

1. Johnson KA, Dosenbach NUF, Gordon EM, et al. Proceedings of the 11th Annual Deep Brain Stimulation Think Tank: Pushing the forefront of neuromodulation with functional network mapping, biomarkers for adaptive DBS, bioethical dilemmas, AI-guided neuromodulation, and translational advancements. Front Hum Neurosci. 2024;18:1320806.

2. National Institutes of Health. BRAIN Initiative research leads to FDA approval of adaptive deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Published March 6, 2025. https://braininitiative.nih.gov/news-events/blog/brain-initiative-research-leads-fda-approval-adaptive-deep-brain-stimulation