Balloon Angioplasty for Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension

August 1, 2025

By Michael H. Crawford, MD, Editor

Synopsis: A multinational, prospective registry of balloon pulmonary angioplasty has shown that significant improvement in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension can be accomplished with few complications and no periprocedural mortality.

Source: Lang IM, Brenot P, Bouvaist H, et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: Results of an international multicenter prospective registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025;85(23):2270-2284.

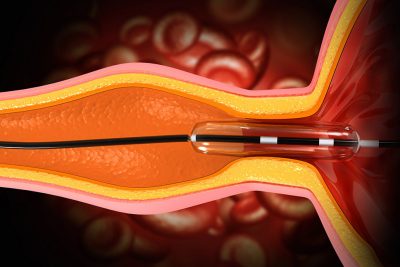

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is caused by mechanical obstruction of pulmonary arteries by thrombus organization. It can be alleviated by surgical pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA), but about 40% of patients are not eligible for PEA because of technical complexities and comorbidities.

In 2012, Japanese interventionalists perfected balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA). It has been used with increasing frequency in the United States and Europe employing coronary wires and balloons. Thus, this prospective international registry study from 18 centers in 10 countries (eight European countries and the United States and Japan) is of interest.

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the complication rate of BPA. Secondary aims included hemodynamic changes, the role of pulmonary hypertension (PH) medications, and mortality. Between 2018 and 2020, 484 patients (294 in Europe,102 in Japan, and 88 in the United States) with CTEPH who had at least one BPA session were enrolled and were followed through 2022. Their mean age was 65 years and 59% were women. The patients’ baseline mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) was 42 mmHg and mean pulmonary vascular resistance (mPVR) was 604 dynes/s/cm-5.

Japanese patients were predominantly small women with lower mPAP. BPA was performed 2,327 times on the 484 patients, with 459 patients having more than one session. Venous access was mainly from the groin in the United States and Europe and the neck in Japan. There was an average of 39 days between sessions overall (seven days in Japan), and the average number of sessions per patient was five. Almost all the patients were taking oral anticoagulants.

After a median follow-up of 26 months, mPAP decreased by 15 mmHg and mPVR by 330 dynes/s/cm-5. There also were significant improvements in functional class, six-minute walk distance, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), the Borg dyspnea index, and arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2). Any procedural complication was noted in 11% of the sessions in 34 patients. Thoracic complications (e.g., hemoptysis, pulmonary artery dissection) occurred in 9% of sessions in 29 patients. Nonthoracic complications (e.g., access site, contrast-associated renal injury) occurred in 3% of the sessions in 11% of the patients. These percentages were much lower in Japan. There were no procedural deaths.

During follow-up, there were 21 all-cause deaths, of which seven were PH-related. Three-year survival was 94%. The authors concluded that BPA significantly improves hemodynamics, SaO2, six-minute walk distance, NT-proBNP, and the Borg dyspnea index without any periprocedural deaths and few complications, consisting mainly of mild hemoptysis.

Commentary

PEA still is a successful procedure for treating CTEPH, but it is not feasible in almost half of patients. Thus, BPA is a welcome addition to our armamentarium. Although initially tried in the early 2000s, it was not embraced until the Japanese perfected the procedure in the second decade of this century. Subsequently, the International CTEPH Association designed this multicenter registry to assess the beneficial effects and complications of BPA.

About three-quarters of the patients were from Europe and the United States, but the patients from Japan are noteworthy because they have significantly smaller body mass indexes, lower mPAP and mPVR, and fewer were taking PH medications. Although the Japanese interventionalists performed the same number of treatment sessions (five) as in Europe and the United States, they treated more lung segments per session and more total segments per patient. Also, they did not sedate their patients, used less intravenous contrast, and exposed the patients to less radiation. Clearly, they had benefited from their longer experience with BPA.

In the entire cohort, the changes in hemodynamics were impressive, with a 57% decrease in mPVR. However, 52% still had an mPAP ≥ 25 mmHg and many still were taking PH drugs (59%). There were few procedural complications; the most common was mild hemoptysis, which was easily managed. The risk factors for thoracic complications were female sex, taking PH medications, and having a high mPVR. The most powerful risk-lowering factor was being Japanese. On the other hand, there were no procedural deaths, and the three-year mortality was the same for the three geographic areas.

There were limitations to this registry study. Because of COVID, only two-thirds of the patients had follow-up right heart catheterizations. PH drug use effects could not be ascertained, and some of the improvements in hemodynamics could be the result of PH drug administration post-BPA. Of course, this is a prospective, observational study, so cause and effect cannot be determined. A randomized controlled trial of BPA vs. PEA is being planned. At this time, the patient and practice differences, the low mortality and complications, and the 94% three-year survival are compelling. Of note, the best results were obtained if more than five lesions were opened, the mPAP was > 40 mmHg at baseline, and BPA was performed at a center with considerable experience. One hopes, as more experience with BPA is gained in Europe and the United States, we can have outcomes equal to the more experienced Japanese interventionalists.

Michael H. Crawford, MD, is Professor Emeritus of Medicine and Consulting Cardiologist, UCSF Health, San Francisco.