Acute Aortic Dissection

December 15, 2025

By Daniel Migliaccio, MD, FPD, FAAEM, and Benjamin Malinda, DO

Executive Summary

- The incidence of acute aortic dissection in the United States is approximately three per 100,0000 each year, which is about 80 times less common than the incidence of acute myocardial infarction.

- Aortic dissection results from separation of the intima from the medial layer of the aortic wall, creating a false lumen parallel to the true aortic lumen.

- About two-thirds of acute aortic dissection cases involve the ascending aorta.

- The classic syndrome of acute aortic dissection is sudden, severe chest, back, or abdominal pain that is maximally severe at onset, often described as ripping or tearing.

- While physical examination findings can be suggestive of the diagnosis, only about 30% of patients with acute aortic dissection will manifest them.

- The most common misdiagnosis of acute aortic dissection is acute myocardial infarction.

- Most patients presenting with acute dissection will have some abnormality on a chest radiograph, such as mediastinal enlargement, so it is a good initial imaging study to confirm the need for additional advanced imaging, but because of the low sensitivity, is not appropriate to rule out dissection.

- The gold standard for the diagnosis for acute aortic dissection is the computed tomography angiography (CTA).

- Emergency management of acute aortic dissection involves the use of intravenous beta-blockers to reduce heart rate and reduce systolic impulse to halt propagation of further dissection, with a goal of maintaining the heart rate less than 60 beats/minute.

- The next treatment goal is to reduce the systolic blood pressure to between 110 mmHg and 120 mmHg, using fast-acting calcium channel blockers nicardipine or clevidipine.

- Patients with dissections involving the ascending aorta and those with dissection impairing blood flow from aortic branches should have emergency surgical evaluation.

- Patients with dissections involving only the descending aorta and without impaired blood flow from aortic branches usually are managed medically.

Introduction

Acute aortic syndromes, such as dissection, ulcers, or intramural hematomas, are infrequent presentations with a high rate of mortality. While each has a described classic presentation, the absence of these findings is not reliable to adequately exclude the diagnosis and, thus, they provide a significant challenge to emergency clinicians.

The basic principle of all three syndromes starts with disruption of the aortic intima from the aortic media. In a classic aortic dissection, there is a separation of the intima and media layers of the aortic wall. The propagation of this separation can result in life-threatening malperfusion syndromes affecting any organ system in the body, with some of the most common complications being ischemic stroke, ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), or ischemic bowel.1-5

In a penetrating ulcer, an atherosclerotic plaque can erode through the intimal wall, leading to a traditional dissection, or penetrate further, producing free wall rupture of the aorta with hemorrhage into the pleural space.1-6 Intramural hematomas can develop spontaneously or in conjunction with the other described pathologies and can have similar complications.2,4

Aortic dissection is estimated to occur in 2.9 to 3.5 per 100,000 patients per year, with a high predilection for older male patients.2,4,7 Risk factors for this diagnosis typically include disease processes, specifically chronic diseases such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or genetic connective tissue diseases, that lead to the degeneration of the intima of the aortic wall. Traditionally, conditions such as Marfan syndrome, vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, or hypermobility syndromes such as Loeys-Dietz are thought of as genetic risk factors.1-4 Additionally, lifestyle factors, such cocaine use, smoking, or other stimulant medication use, also can pose significant risk to the development of aortic dissection.

As with other rare but lethal acute illnesses, clinical suspicion for ongoing aortic pathology is key in diagnosis. Timely management with vasoactive agents for heart rate and blood pressure management are critical actions for emergency physicians to improve patient outcomes. In close collaboration with surgical colleagues, emergency clinicians can improve outcomes by limiting delays in diagnosis or initial stabilization in this time-sensitive diagnosis.1-4,8

The purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive review of aortic dissection from the perspective of the emergency clinician, including pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of acute aortic dissection and its complications.

Pathophysiology

The aorta is composed of three layers of tissue, the intima, media, and adventitia, the same as all arterial vasculature. The intima is the innermost layer, the media is the muscular middle layer that provides the vessel with its elasticity, and the adventitia is the outermost and strongest of the three layers containing mostly connective tissue and the vessels that supply the aorta with its blood supply, called the vaso vasorum.8

The aorta is delineated into five broad regions: the aortic root, the ascending aorta, the aortic arch, the descending aorta, and the abdominal aorta. The aortic root extends from the annulus of the aortic valve to the sinotubular junction of the aorta leading into the ascending aorta, which terminates at the origin of the innominate (brachiocephalic) artery. The aortic arch follows and terminates at the left subclavian artery. This is the region that serves as the origin for the great vessels, the brachiocephalic, the left common carotid, and the left subclavian arteries.

This leads finally to the descending aorta delineated from the abdominal aorta by the diaphragm. The abdominal aorta is further delineated into 11 zones for endovascular interventions, which is outside the scope of this review.

The aorta is exposed to large shear stresses with every ventricular contraction. These shearing forces are highest in the outer wall of the proximal descending thoracic aorta, typically just distal to the left subclavian artery. Other areas of high shear stress are seen at the outer curve of the ascending aorta attributed to the rapid changes in the direction of blood flow seen in the arch during the cardiac cycle.9

An aortic dissection begins with a tear to the innermost layer of the aortic wall. Blood under pressure from the aortic lumen subsequently dissects the intima from the media. The pulsatile changes in pressure result in the propagation of this dissection. The dissection results in the creation of a false lumen where blood will be present alongside the true lumen of the aorta.1,2 The dissection can progress in either an antegrade or retrograde fashion.

Complications from aortic dissection can arise from a variety of pathways. For example, a dissection involving the ascending aorta can propagate backward into the space between the two layers of pericardium, causing hemopericardium and subsequent tamponade. Retrograde dissection may enlarge the aortic root beyond the valve leaflet size, leading to acute aortic insufficiency and, often, cardiogenic shock.

If the dissection involves aortic branches, end organ ischemia may result.1,2 It can affect the coronary arteries, leading to STEMI, or the carotids, causing acute ischemic stroke.1,2 In dissections of the descending aorta, mesenteric arteries can be involved, leading to gut ischemia, or renal arteries can be affected, leading to kidney injury. Involvement of the femoral arteries can lead to critical limb ischemia. Dissections that perforate through the adventitia can cause large amounts of bleeding into the thorax or abdomen, leading to hypovolemic shock.1,2

Tears in the aortic intima arise by underlying degeneration of the vessel wall tissue, which can be secondary to a variety of diseases. Most typically, chronic and untreated hypertension is the culprit of such degeneration; this can work in tandem with the development of atherosclerotic plaque and other cardiovascular risk factors like hyperlipidemia. Additionally, genetic connective tissue syndromes, such as Marfan syndrome or vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, result in weakening of the structural tissues that comprise the arterial intima, predisposing them to failure. Bicuspid aortic valve results in early aortic stenosis and subsequently higher shearing forces on the aortic intima.2,10-12

Two commonly accepted classification systems are used to classify aortic dissection. The Stanford classification is the simpler of the two, with type A and type B dissections. Type A dissections involve the ascending aorta and type B dissections only involve the descending aorta. If a dissection were to involve both the ascending and the descending aortas, this would be classified as a type A dissection.

The DeBakey classification is more nuanced. Type I dissections start in the ascending aorta and continue through the arch and into the descending aorta. Type II dissections originate in the ascending aorta and remain confined to that region. Type IIIA dissections originate in the descending aorta and do not extend to the abdominal aorta. Finally, type IIIB dissections originate in the descending aorta and extend into the abdominal aorta.1,2,13 Approximately two-thirds of aortic dissections will be a Stanford type A and the remaining one-third will be type B.14 For the purposes of this paper, the description of dissections will follow the Stanford convention.

Classification of a dissection is highly important because it guides the patient’s management in the emergency department (ED). Surgical colleagues always should be involved in the care of a patient with an acute aortic dissection; however, the management of the patient changes drastically in an ascending dissection as opposed to a descending dissection. Type A dissections require emergent operative management because of the potential complications associated with disruption of the aortic arch and the associated great vessels. Type B dissections usually are managed with medical therapies focusing on impulse control and pain management but can be complicated with various malperfusion syndromes. If present, malperfusion syndromes indicate the need for operative management.

The classification of dissection also dictates the kind of complications that may be present. In Stanford type A dissections, pericardial hemorrhage and cardiac tamponade are seen in up to 20% and myocardial ischemia occurs in 10% to 15%. Stroke or neurologic symptoms are seen in 17% to 29% of patients, with stroke occurrence higher in patients presenting with other malperfusion syndromes. Malperfusion syndromes also are seen in type B dissections and account for about 20% to 30% of overall complications. Initially uncomplicated type B dissections will become complicated after 30 days in up to 20% of patients. In general, type A dissections have a higher rate of overall complications than type B dissections.1,2,4

Clinical Presentation

Aortic dissection presents a unique challenge to diagnosis because of the number of ways it can present. Traditionally, the presentation of aortic dissection is described as a patient with cardiac risk factors with the complaint of sudden and severe chest, back, or abdominal pain. The pain severity is described as maximal upon onset, as opposed to gradually increasing. Frequently the pain is described as radiating from the chest to the back with an associated sensation of tearing.

Some specific features increase the likelihood of the diagnosis. The description of ripping and tearing pain to the back has a positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 42.1. Other symptoms that are associated with aortic dissection with a high likelihood ratio include a new pulse deficit (LR+ = 31.1), hypotension (LR+ = 17.2), a new murmur consistent with aortic regurgitation (LR+ = 9.4), a history of an aortic aneurysm (LR+ = 6.35), and a new focal neurologic deficit (LR+ = 5.26).5,15,16 Unfortunately, for the majority of patient presentations in acute aortic dissection, physical examination findings will be normal, with only approximately 30% of patients having physical examination findings as described. 7,15

Overall patient presentations can mimic numerous other pathologies depending on what branching vessels are affected by the dissection. Dissection can mimic cardiac emergencies like acute STEMI or pericardial tamponade. Because of the similarity of symptoms, aortic dissection frequently is misdiagnosed as acute coronary syndrome in up to one-third of cases.5,17 Shock or hypotension can be a presenting symptom if the dissection involves the aortic root or the aortic valve annulus, leading to acute aortic regurgitation and cardiogenic shock. Hemorrhagic shock also can be seen with aortic dissection in cases of rapidly expanding hematoma or bleeding into the pleural space.

Dissection can mimic pulmonary emergencies like pulmonary embolism because of the common presence of chest pain, dyspnea, and tachycardia. Aortic dissection can mimic neurologic emergencies, such as ischemic stroke, syncope, ataxia, altered mental status, and Horner’s syndrome, if the dissection extends into the carotid arteries.18,19 There also are documented cases of patients presenting with isolated limb paresthesias or plegia as the only symptom.20 Similarly, patients also can present with acute limb ischemia and associated limb pain. Dissection can present with obscure signs of ischemia in any organ. Patients could become acutely anuric with abdominal pain as a dissection causes malperfusion of the kidneys, or diffuse abdominal pain with pain out of proportion if the dissection causes acute mesenteric ischemia.1,2,21,22

Although pain is the most common presenting symptom, and acute pain increases the likelihood of acute dissection, pain also can be described as mild or worsening chronic pain that resembles musculoskeletal complaints.23 To further complicate diagnosis, patients also can present with painless dissection. These presentations are infrequent, accounting for 5% to 10% of patients with aortic dissection.7,24,25 In the literature, most painless dissections have some degree of neurologic symptoms, like those mentioned earlier, with some kind of neurologic finding 44% of the time.26

Diagnostic Approach

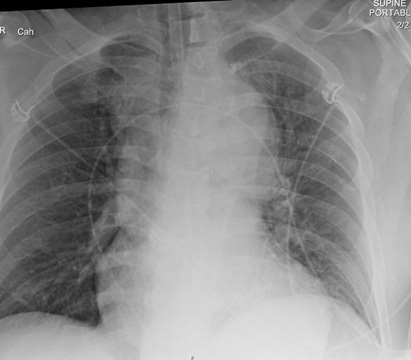

Imaging is the mainstay of diagnosis for aortic dissection or other aortic syndromes. Chest radiograph is a fast mode of initial evaluation. However, X-ray findings of aortic dissection are not reliable for diagnosis, and this evaluation is not sufficient to rule out acute aortic syndromes. The most common finding with acute aortic dissection on the chest radiograph is mediastinal enlargement, assessed to be about 54% sensitive and 92% specific.27 (See Figure 1.) Most patients presenting with acute dissection will have some abnormality on chest radiograph, so for this reason, it is a good initial imaging study to confirm the need for additional advanced imaging. However, because of the low sensitivity, it is not appropriate to rule out dissection. Also, the chest radiograph can be used to ensure that there is no additional pathology or complication contributing to the patient’s presentation, such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, or pneumonia.

Figure 1. Chest Radiograph with Wide Mediastinum |

|

Image courtesy of Daniel Migliaccio, MD |

More specific but less common chest radiographic abnormalities seen in acute aortic dissection are widening of the aortic knob, an abnormal aortic contour, pleural effusions, or the calcium sign, which is the separation of intimal calcifications from the border of the aortic knob.1,4

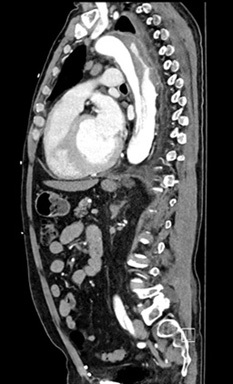

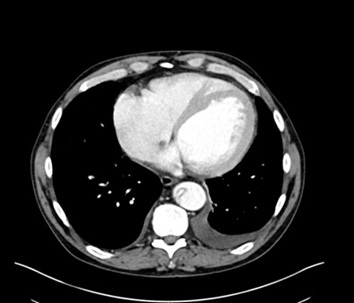

The gold standard for diagnosis is the computed tomography angiography (CTA) because of its speed, high sensitivity, and high specificity for aortic pathology. The sensitivity and specificity of CTA for acute aortic dissection approaches 100%.1,4,28-30 (See Figures 2-4.) An important point when ordering the CTA is to specifically state the reason, such as “possible aortic dissection,” so the correct CT imaging protocol will be done to maximize accuracy.

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is a good imaging modality for diagnosis of aortic dissection, with a sensitivity ranging from 80% to 100% and specificity of 90% to 100%. However, the feasibility is not compatible with the ED. TEE requires sedation, uses equipment that is not regularly kept in the ED, and requires a clinician who is trained in the use and interpretation of TEE which, at present, does not usually include an emergency physician. For these reasons, TEE usually is not a recommended study in the ED for diagnosis of aortic dissection.

Figure 2. CTA Showing Dissection of the Descending Thoracic Aorta with Sagittal View |

|

Image courtesy of Daniel Migliaccio, MD |

Figure 3. CTA Showing Intimal Flap in Dissection of the Descending Thoracic Aorta with Transverse View |

|

Image courtesy of Daniel Migliaccio, MD |

Figure 4. CTA Showing Aortic Dissection in Abdominal Aorta with Sagittal View |

|

Image courtesy of Daniel Migliaccio, MD |

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is an ultrasound imaging modality that is more readily available in the ED and can be rapidly deployed at the bedside. Unfortunately, TTE is not a reliable method for diagnosis or exclusion of aortic dissection, specifically of the thoracic aorta. This is because of the lack of sensitivity that frequently can be attributed to technical limitations when trying to visualize the ascending aorta, aortic arch, or thoracic aorta. Thus, because of these limitations, TTE is not recommended for the definitive diagnosis of thoracic aortic dissections.

However, there are findings on TTE that would raise concerns for aortic dissection, particularly if done using point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS). Detection of aortic intimal flap (indicating the intimal tear), aortic wall thickening or dilatation greater than 40 mm, new major aortic regurgitation that can include cusp prolapse, or pericardial effusion (especially with echogenic material suggestive of hemopericardium) all are findings on TTE that are concerning for aortic dissection. Dilatation of the aortic root also can be seen in type A dissection, and dilation of 4.5 cm or more is sensitive for dissection but is not specific.1,13,31 (See Figures 5 and 6.) Observing these abnormalities on TTE should prompt immediate CTA of the aorta and consultation with surgical colleagues.8

Figure 5. Cardiac POCUS Parasternal Long Axis View Showing Intimal Flap |

|

POCUS: point of care ultrasound Image courtesy of Daniel Migliaccio, MD |

Figure 6. POCUS Sagittal View Showing Intimal Flap in Abdominal Aorta |

|

POCUS: point of care ultrasound Image courtesy of Daniel Migliaccio, MD |

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is another option for imaging. MRA has a sensitivity of 95% to 100% and a specificity of 94% to 98% for aortic dissection.28 Despite the high level of accuracy, MRA is not a good imaging modality for the diagnosis of acute dissection in the ED. MRA is a specialized exam that is not always available from the ED. Additionally, the time to acquire an MRA is significantly longer than for CTA. The delay in management an MRA would introduce could result in complications or extension of the intimal flap of a dissection prior to the initiation of treatment. MRA is an ideal study for the surveillance of known aortic disease given the lack of radiation exposure with repeat studies.

Some laboratory tests can contribute to the diagnosis of aortic dissection. It should be noted, there are no laboratory studies that can definitively diagnose or rule out an aortic dissection. If there is concern based on the history and physical examination, imaging should be pursued. Additionally, definitive management is dependent on imaging findings. For this reason, laboratory evaluation is best suited to screening for acute disease.

D-dimer is the most cited laboratory study for aortic dissection screening since it is highly sensitive. A positive D-dimer can point to dissection, but it is not specific since it also can be seen in other presentations like pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. A negative D-dimer in patients with a low pre-test probability can help exclude dissection. Unfortunately, D-dimer can be normal, even in the setting of acute aortic disease. Because of this, D-dimer is not recommended as a single test to rule out aortic dissection.1,2,32

D-dimer is most useful when used in conjunction with history, physical, and validated risk stratification tools like the Aortic Dissection Detection Risk Score (ADD-RS). This decision tool takes into account any high-risk condition associated with dissection, such as Marfan syndrome, family history, or aortic valve disease in conjunction with high-risk features in the history and high-risk examination findings. (https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/4060/aortic-dissection-detection-risk-score-add-rs). If the ADD-RS score is ≤ 1 and the D-dimer is < 500 ng/mL, the risk for acute aortic dissection is very low, and it would be reasonable to not pursue CTA.32

There is emerging evidence for additional laboratory testing that may have a diagnostic value when evaluating for dissection, such as tenascin-C (TN-C), fibrinogen degradation products (FDP), and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). One study found that TN-C had both high sensitivity and specificity for acute aortic dissection and did well to distinguish dissection from acute coronary syndromes.33

There also are some tests that should be ordered preemptively if there is concern for aortic dissection. Basic laboratory evaluation, including liver function and lactate, is helpful to evaluate for end organ dysfunction looking for acute renal failure, ischemic hepatitis, or elevated lactate associated with hypoperfusion. Coagulation studies should be collected to evaluate for complicating factors such as coagulopathy or if the patient is anticoagulated. A transfusion type and screen also should be collected preemptively in the ED in preparation for operative management.

It is important to recognize that errors in diagnosis are common in aortic dissection. The most frequent complaint seen in acute aortic dissection is chest pain, contributing to the misdiagnosis of the more common condition of acute coronary syndrome. In general, aortic dissection is misdiagnosed in about one-third of cases. This is because of the symptom overlap with other conditions and the lack of classic findings on screening studies such as chest radiograph.34 The most predictive clinical features and risk factors for missed diagnosis of aortic dissection are atypical or absent pain, the absence of classic physical exam findings, overlap with other common conditions, and presentation to non-tertiary centers. It is imperative to maintain a broad differential in the undifferentiated patient. Both anchoring biases and premature closure easily can result in misdiagnosis and poor patient outcomes.

Emergency Department Management

Patients who present with a history concerning for aortic dissection should become a priority for evaluation in any ED. However, their initial assessment will resemble the assessment of any critically ill patient, with initial focus on the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation, and intravenous access, followed closely by vital signs. Triage personnel should be familiar with red flags for dissection as described earlier, such as sudden-onset tearing chest and back pain.

Airway management is challenging in acute aortic dissection. Intubation should be avoided when possible because positive intrathoracic pressure can increase aortic wall stress and risk of rupture. Intubation should be reserved for patients who have respiratory failure, are unable to oxygenate, are hemodynamically unstable, or who have agitation that cannot be managed adequately with medication administration and that is complicating management of the patient’s heart rate and blood pressure.1,2

Aortic dissection is a time-sensitive diagnosis. In type A dissections, mortality increases by approximately 1% to 2% per hour.1,13 As a result, timely diagnosis and subsequent management is paramount. After the diagnosis of aortic dissection, the mainstays of therapy in the ED are pain control and systolic impulse control. Rapid administration of analgesia can help to decrease sympathetic tone, which works synergistically with impulse control to decrease the shearing forces that are placed on the intimal flap. Pain management typically is pursued with intravenous opioid medications. These medications can be dosed as a bolus; however, infusions can be helpful for ongoing management. Short-acting medications that are easily titratable, such as intravenous fentanyl, can be a good option for management of acute pain. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary sedation when using opioid medications since frequent reassessment is needed to evaluate for developing complications. However, additional options for pain control are limited because nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) possibly can increase the risk of bleeding, and other medications like ketamine can increase blood pressure and heart rate, which is contraindicated in acute aortic dissection.

The other aspect of dissection management is systolic impulse control, which aims to decrease the shear forces that are exerted on the intimal flap in dissection. There are two aspects to impulse control: decreasing heart rate and systolic blood pressure. Vasoactive agents should be started to achieve a heart rate of less than 60 beats per minute and a systolic blood pressure of 100 mmHg to 120 mmHg. Invasive blood pressure monitoring is recommended for ongoing management of blood pressure because it can provide real-time feedback for titration of vasoactive medications.8,13 (See Table 1.)

Table 1. Medications to Control Heart Rate and Blood Pressure in Acute Aortic Dissection |

Esmolol

|

Nicardipine (intravenous [IV])

|

Clevidipine IV

|

Nitroprusside (Sodium nitroprusside)

|

Fenoldopam

|

Labetalol (option for single drug management)

|

Diltiazem IV (if beta-blockade contraindicated)

|

Initial vasoactive agents should focus on beta-blockade by intravenous administration. Beta-blockade is pursued first to avoid reflex tachycardia that would be seen when starting many antihypertensive agents. If the blood pressure still is elevated above goal with beta-blockade, then additional blood pressure control can be pursued. The agent of choice for beta-blockade is esmolol because of its short half-life, allowing for quick titration to a goal heart rate of less than 60 beats per minute. Dosing may vary depending on clinical protocols but generally is given as a 500 mcg/kg bolus, followed by an infusion of 50 mcg/kg/minute. The medication can be titrated upward by 25 mcg/kg/minute to 50 mcg/kg/minute every five to 15 minutes, with a maximum dose of 300 mcg/kg/minute until the heart rate is less than 60 beats per minute.

Additional blood pressure control can be achieved with fast-acting calcium channel blockers. These medications are easily titratable medications and frequently are used in the ED. Both nicardipine or clevidipine are appropriate choices. Nicardipine can be started at 5 mg per hour and titrated upward to a maximum of 15 mg per hour. Some other options for intravenous blood pressure control include nitroprusside or fenoldopam. Labetalol also can serve as an effective single drug for impulse control either using boluses or infusion. If beta-blockade is contraindicated because of concerns for bronchospasm, then non-dihydrapyrimidine calcium channel blockers diltiazem or verapamil can be considered. (See Table 1.)

All patients with acute aortic dissection should receive an emergent surgical consultation while in the ED. Stanford type A dissections or type B dissections with evidence of malperfusion syndromes should be taken for immediate operative management. Stanford type B dissection without complications or malperfusion syndromes primarily can be managed medically with continued analgesia and systolic impulse control with close monitoring for malperfusion syndromes.

In-depth discussion about the options for operative management are outside the scope of practice for the emergency physician. However, in brief, the type of repair will depend on the patient and sections of the aorta involved. The mainstays of surgical repair are endovascular techniques like vascular grafting for arch replacement or frozen elephant trunk technique. Patients can be considered for open repair if their anatomy is not amenable to endovascular repair.

Anticoagulation is not a contraindication for immediate surgical management; however, it does increase operative mortality. Initial management in anticoagulated patients does not change, with a focus on control of pain, heart rate, and blood pressure. If there are emergent indications for surgery, reversal agents should be administered, or intraoperative filtration can be used. Operative management can be delayed for 12-24 hours if needed to allow for the reversal of anticoagulation if the patient is stable without indication for immediate surgical management. Ideally, for surgical optimization, patients who are taking warfarin have a goal international normalized ratio (INR) of < 1.5 prior to surgery, and patients taking direct oral anticoagulants would have the medication discontinued for 48-96 hours.35-37

All patients who present with acute aortic dissection require admission for ongoing management, whether surgical or medical. Almost all patients require intravenous medications, frequent assessments, and invasive blood pressure monitoring that necessitates intensive care unit (ICU) level of care. If there is no availability for surgical management with cardiothoracic or vascular surgical services, the patient should be transferred to the nearest facility with those services available using the most expeditious means of transport. Discussion of code status and goals of care can ensure that the patient’s disposition meets their expectation for care.

Special Considerations

Aortic Dissection in Pregnancy

Pregnancy can increase the risk of aortic dissection in female patients. Management of these patients requires multidisciplinary management and individualized risk assessment. Women with underlying genetic aortopathies, such as Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, or Turner syndrome, are at the highest risk of dissection because of the hemodynamic and hormonal changes during pregnancy that increase aortic wall stress and dilation. These aortopathies account for up to 68% of aortic dissections in pregnancy.38-40 The incidence of aortic dissection in pregnancy is highest in the third trimester, and the risk remains increased up to 12 weeks postpartum.

Diagnosis of aortic dissection in pregnant patients can be complicated. The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology recommend limiting the use of CTA for imaging, even for the diagnosis of aortic dissection, in pregnant patients because of the ionizing radiation exposure. The use of MRA is preferred given its high accuracy and lack of radiation exposure. TTE also is recommended.1

However, both MRI and TTE have significant limitations in the diagnosis of aortic dissection, as previously noted. If a patient is not clinically stable for evaluation via MRA, then CTA should be considered. The use of CTA should be guided by clinical judgment, the stability of the patient, and available techniques for decreasing radiation exposure through shielding or reduced dose techniques. Notably, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends the use of CTA for diagnosis of dissection if clinically indicated. However, a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits should be completed prior to CTA imaging when possible. It should be noted that typical fetal radiation from chest CTA is low, and with modern low-exposure techniques, is well below the threshold associated with teratogenicity or increased fetal abnormalities.41

Management of dissections in this patient population is dependent on the gestational age. For type A dissections in the first and second trimesters, urgent aortic surgery with fetal monitoring is the recommended treatment. In the third trimester, urgent cesarean delivery followed immediately by aortic surgery is recommended to optimize maternal and fetal survival. For type B dissection, management remains similar when compared to non-pregnant patients, with medical therapy being the mainstay of treatment unless there are complications that would necessitate surgical management.37-40

Pediatric Dissection

Although rare, aortic dissection can present in pediatric patients. Most often, dissection in pediatric patients is associated with genetic syndromes or congenital heart disease, such as genetic aortopathies like Marfan syndrome, vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, or Turner syndrome, and congenital disease like bicuspid aortic valve or aortic coarctation. The symptoms of aortic dissection in pediatric patients are similar to those seen in adults with additional presenting syndromes like pallor or pulselessness.

As with adults, diagnosis requires a high clinical suspicion and identifying risk factors. TTE can serve as an easy screening tool that avoids radiation exposure looking for aortic root dilatation and abnormalities in the ascending aorta. However, much like in adults, CTA remains the gold standard for diagnosis of acute dissection. The management of aortic dissection in the pediatric population parallels management in the adult population, with surgical repair of type A dissection and medical management of type B dissection unless there is an accompanying malperfusion syndrome. Multidisciplinary care, including cardiology and genetics, is essential to improving outcomes.42

Substance Use

Substance use, specifically the use of cocaine and amphetamines, significantly increases the risk of aortic dissection, especially in younger adults who do not have the typical risk factors for dissection like hypertension and atherosclerotic disease. The use of amphetamines is associated with a more than threefold increased risk of aortic dissection that is independent of other risk factors.43 Cocaine use is implicated in 1.8% of all aortic dissection cases.

The presumed mechanism of this relationship is thought to be the abrupt and severe hypertension with the catecholamine surge associated with the use of these substances. There also is some evidence that use of these medications can directly impair the integrity of aortic connective tissue. The proposed mechanism is that chronic exposure promotes vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction predisposing to dissection.1,43,44

The presentation of aortic dissection in this patient population is similar to previously described presentations, with the caveat that patients may be significantly younger and their presentation is more likely to be associated with a hypertensive crisis. Additionally, type B dissections are most common in these populations. In-hospital mortality for these patients can be lower than the general population, thought to be secondary to the younger age at presentation; however, long-term outcomes tend to be worse for those who have continued substance abuse after discharge.43

Traumatic Dissection

Traumatic aortic dissection or blunt traumatic aortic injury varies greatly in treatment and classification when compared with nontraumatic/spontaneous dissection. Treatment is guided by injury severity and specific imaging findings. The standard study for diagnosis is CTA, which traditionally is part of CT imaging in the setting of traumatic injury.

There is a grading system separate from the Stanford and DeBakey systems for traumatic aortic injury that is designed by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. Grade I is classified as a minor injury involving only the intimal layer of the aorta. Usually a grade I injury reflects an intimal tear or defect without any abnormality in the external contour of the aorta or hematoma, and it is managed similar to a Stanford type B dissection with strict blood pressure and heart rate control with a goal of systolic blood pressure less than 100 mmHg and a heart rate of less than 100 beats per minute.

Grade II involves blood within the aortic wall/an intramural hematoma without an external contour abnormality or pseudoaneurysm. If there are high-risk features on imaging like a large mediastinal hematoma, mass effect, pseudocoarctation, or arch involvement, then thoracic endovascular repair (TEVAR) is recommended. However, if these high-risk features are not present, then conservative management with a focus on blood pressure and heart rate may be appropriate. This is a decision that would be made with surgical colleagues in consultation.

Grade III is a contained rupture of the aortic wall, with blood collecting outside the intima and media, but remains within the adventitia. This results in a focal outpouching of the aortic contour. Grade IV is a full-thickness tear of the aortic wall with free extravasation of blood into the mediastinum or pleural space. In both these cases, TEVAR is the first-line management, assuming that the patient’s anatomy is amenable.13 (See Table 2.)

Table 2. General Recommendations for Management of Traumatic Aortic Dissection |

Grade I

|

Grade II

|

Grade III

|

Grade IV

|

TEVAR: thoracic endovascular aortic repair |

TEVAR is the preferred approach for most traumatic aortic dissections as there is lower associated morbidity and mortality compared to open surgery, especially in polytrauma patients. However, if there is unsuitable anatomy or if endovascular repair fails, open surgery is an alternative.1,45

Interprofessional Collaboration

Aortic dissection is a time-sensitive pathology that requires precise orchestration of resources in the ED. Team dynamics between physicians, nurses, radiology technicians, and consultants can make a significant difference in the management and outcome of these patients. Open discussion between triage or the emergency services team and the emergency physician can help raise the alarm to aortic pathology, and pointed discussion between the emergency team and imaging teams can expedite diagnostic imaging for continued management. Independent review of imaging and prompt discussion with radiology colleagues can expedite information that is essential for surgical colleagues.

When consulting with cardiology or surgical teams, it is important to have the appropriate information available because it will guide the course of management. Important information includes the results of imaging, classification of the dissection, and evidence of any malperfusion syndromes or other complications that are essential knowledge for management and surgical planning if indicated.

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association both strongly endorse the use of standardized protocols when caring for patients with acute aortic dissection. Protocolized approaches promote prompt diagnosis, rapid initiation of therapy, and timely surgical or endovascular intervention. Protocols also can facilitate complication-specific management and improve coordination among emergency, cardiology, and surgical teams. The concept of protocolization is supported by the fact that aortic dissection is a highly time-sensitive pathology where mortality increases significantly with delays in diagnosis and management.1 High-volume centers with established protocols report better survival rates in part because standardized pathways reduce the variability in care and ensure timely access to definitive treatment.2,8

Simulation-based training provides an opportunity for growth and interdepartmental collaboration for management of this time-sensitive pathology. Simulation plays a critical role in improving clinical outcomes in patients with aortic dissection. Both low- and high-fidelity simulation serve as an integral part of the curriculum for all professionals who are involved with aortic dissection care and provide real-time, hands-on practice in the management of these patients. Additionally, simulation-based training can improve diagnostic accuracy and decrease errors in management. With the practice of these simulations in tandem with protocol-driven care, teams are better prepared to recognize aortic dissection presentations and atypical presentations, initiate appropriate therapies, and mobilize surgical resources.13,36

Future Directions and Research

Advances in imaging for aortic dissection focus on the improvement of CT technology, advances in MRI, and new protocols for ultrasonography. For CT, electrocardiogram-gated CTA is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of aortic dissection because it decreases motion artifacts during imaging, particularly in the aortic root and ascending aorta. Multiphase and delayed-phase CT are essential for post-intervention surveillance and the identification of operative complications like endothelial leaks. MRI research is focused on noncontrasted MRA and other advanced sequences for four-dimensional flow MRI to evaluate flow dynamics and wall shear stress. Emerging protocols for hybrid positron emission tomography (PET)/MRI can evaluate for anatomic and molecular risk of dissection, particularly the assessment of inflammation in the aortic wall. Additional imaging modalities like TTE and TEE can be invaluable in bedside assessment and intraoperative management.1,29,31

Although currently there is no laboratory evaluation or biomarker that can adequately evaluate for aortic dissection, there is ongoing research for multiple novel biomarkers. Emerging biomarkers include micro ribonucleic acids (microRNAs), smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, calponin, and multiple metabolic and inflammatory markers. While some markers, such as mircoRNAs, show potential for high specificity, none of these biomarkers have gone through rigorous testing to be appropriate for routine clinical use.1,46-50 There is ongoing research into metabolomic and proteomic evaluations as well. Recent studies have identified panels of metabolites and cytokines that may aid in differentiating myocardial infarction from dissection, but these tests also need more robust validation.48,49

There also are multiple decision tools that are in development for use in the diagnosis of aortic dissection. The ADD-RS in association with D-dimer testing is the current standard for decision tools.32 The AORTAs score is a simplified assessment tool that uses six clinical variables as weighted points in association with an age-adjusted D-dimer. This scoring tool showed a higher sensitivity compared to ADD-RS in limited studies.51-53 There are additional tools that use POCUS and D-dimer for risk stratification. The PROFUNDUS study used ultrasound assessment for thoracic and abdominal aorta dilatation, intimal flap, or abnormal wall structure as well as evaluation for pericardial effusion or acute aortic regurgitation in conjunction with D-dimer and clinical risk scoring to rule out acute aortic syndromes in the ED.53,54 Ongoing research is focused on further validating these alternate decision tools.

There also is ongoing development of an artificial intelligence-driven system for rapid interpretation of CT imaging that has demonstrated high accuracy for detecting aortic dissection in both contrasted and non-contrasted CT imaging. The development of these algorithms is ongoing but is promising and may help facilitate rapid triage and standardize imaging interpretations.55-57

Conclusion

Acute aortic dissection and related aortic syndromes are time-critical diagnoses that, despite their rarity, can have devastating consequences if misdiagnosed or inappropriately managed. The ED is key to diagnosis, with early suspicion, rapid diagnostic evaluation, and immediate stabilization directly influencing patient outcomes. Understanding the pathophysiology of aortic dissection enables clinicians to better interpret its variable and, at times, misleading presentations. Pain may be absent or not consistent with classic presentations. Symptoms can mimic other life-threatening diagnoses, such as acute coronary syndrome or pulmonary embolism, and as a result dissection frequently is misdiagnosed. Clinical suspicion is essential for diagnosis, especially in high-risk patients with undifferentiated chest, back, or abdominal pain.

CTA remains the gold standard for imaging and diagnosis, with bedside options like ultrasound providing useful adjuncts in unstable patients. Risk-stratification tools can provide additional support for diagnosis when used appropriately.

Once diagnosed, acute management in the ED focuses on hemodynamic management with systolic impulse reduction, balancing heart rate reduction and blood pressure management for reduction of stress on the aortic wall. Prompt control of pain, heart rate, and blood pressure using short-acting intravenous beta-blockers and vasodilators is critical. Coordination of care, with timely consultation with surgical colleagues or rapid transfer to centers capable of definitive surgical or endovascular repair, can be lifesaving, especially in dissections involving the ascending aorta.

Looking ahead, several areas look promising. Development of reliable bedside diagnostic algorithms, incorporation of novel serum biomarkers, and use of artificial intelligence for risk prediction could enhance early detection significantly. The implementation of standardized ED-based protocols on time to diagnosis, treatment initiation, and mortality may help optimize care delivery. Ongoing collaboration between emergency medicine, cardiology, radiology, and surgery will be essential to advance these goals.

In conclusion, improving outcomes in aortic dissection depends on a combination of clinical suspicion and system-level preparedness. For emergency physicians, maintaining an index of suspicion and acting decisively remain the most powerful tools in improving patient outcomes.

Daniel Migliaccio, MD, FPD, FAAEM, is Clinical Associate Professor, Division Director of Emergency Ultrasound, Ultrasound Fellowship Director, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Benjamin Malinda, DO, is an emergency medicine resident, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;146(24):e334-e482.

2. Carrel T, Sundt TM, von Kodolitsch Y, Czerny M. Acute aortic dissection. Lancet. 2023;401(10378):773-788.

3. Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma OJ, et al, eds. Aortic Dissection and Related Aortic Syndromes. In: Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2020: Chapter 59.

4. Skiba JF Jr., Norvell C. Aortic dissection. In: EM:RAP CorePendium. Updated Nov. 4, 2024. https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/recN9AXGWMstEm8CO/Aortic-Dissection

5. Lovatt S, Wong CW, Schwarz K, et al. Misdiagnosis of aortic dissection: A systematic review of the literature. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;53:16-22.

6. Foo A, Pozza C. Thoracic aortic dissection presenting with bilateral haemothoraces: A potentially missed diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2023;16(8):e254866.

7. Mussa FF, Horton JD, Moridzadeh R, et al. Acute aortic dissection and intramural hematoma: A systematic review. JAMA. 2016;316(7):754-763.

8. MacGillivray TE, Gleason TG, Patel HJ, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American Association for Thoracic Surgery Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Type B Aortic Dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113(4):1073-1092.

9. Callaghan FM, Grieve SM. Normal patterns of thoracic aortic wall shear stress measured using four-dimensional flow MRI in a large population. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;315(5):H1174-H1181.

10. Khan MYI, Dillman A, Sanchez-Perez M, et al. Tobacco smoking and the risk of aortic dissection in the UK Biobank and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):12083.

11. Gawinecka J, Schönrath F, von Eckardstein A. Acute aortic dissection: Pathogenesis, risk factors and diagnosis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14489.

12. Rodrigues Bento J, Meester J, Luyckx I, et al. The genetics and typical traits of thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2022;23:223-253.

13. Czerny M, Grabenwöger M, Berger T, et al. EACTS/STS Guidelines for Diagnosing and Treating Acute and Chronic Syndromes of the Aortic Organ. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024;118(1):5-115.

14. Gouveia E, Melo R, Mourão M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the incidence of acute aortic dissections in population-based studies. J Vasc Surg. 2022;75(2):709-720.

15. Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): New insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283(7):897-903.

16. Ohle R, Um J, Anjum O, et al. High risk clinical features for acute aortic dissection: A case-control study. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(4):378-387.

17. Zhang Q, Yang DD, Xu YF, et al. De Winter electrocardiogram pattern due to type A aortic dissection: A case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22(1):150.

18. Daou R, Khater DA, Khattar R, Helou M. Aortic dissection presenting as a stroke: A case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2023;44:91.

19. Al Rayess N, Ozgur SS, Challita R, et al. Underappreciated relationship: A case of type A aortic dissection presented with atrial flutter. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2024;12:23247096241308578.

20. Wang X, Li Z. Sudden right lower limb paralysis: An uncommon presentation of type A aortic dissection. Chest. 2025;168(1):e1-e2.

21. Yost G, Yang B. Malperfusion, malperfusion syndrome, and mesenteric ischemia in aortic dissection. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2025;37(2):132-135.

22. Sheng M, Gong W, Zhao K, et al. Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia caused by type B aortic dissection: A case report. BMC Surg. 2022;22(1):214.

23. Li XD, Chen ZJ. Aortic dissection disguised as musculoskeletal condition: A case report and review of literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2025;26(1):863.

24. Ahmed T, Mouhayar E, Banchs J, et al. Extensive painless aortic dissection in a patient with breast cancer. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023;48(8):101253.

25. Riaz S, Ahmed D, Omoregbee BI, et al. Silent stealth: Painless aortic dissection masquerading as heart failure. BMJ Case Rep. 2024;17(9):e261556.

26. Imamura H, Sekiguchi Y, Iwashita T, et al. Painless acute aortic dissection. Diagnostic, prognostic and clinical implications. Circ J. 2011;75(1):59-66.

27. Nazerian P, Pivetta E, Veglia S, et al. Integrated use of conventional chest radiography cannot rule out acute aortic syndromes in emergency department patients at low clinical probability. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(11):1255-1265.

28. Goldstein SA, Evangelista A, Abbara S, et al. Multimodality imaging of diseases of the thoracic aorta in adults: From the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging: Endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(2):119-182.

29. Murillo H, Molvin L, Chin AS, Fleischmann D. Aortic dissection and other acute aortic syndromes: Diagnostic imaging findings from acute to chronic longitudinal progression. Radiographics. 2021;41(2):425-446.

30. McCarthy FH, Burke CR. Imaging for thoracic aortic dissections and other acute aortic syndromes. Cardiol Clin. 2025;43(2):219-227.

31. Sutarjono B, Ahmed AJ, Ivanova A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transthoracic echocardiography for the identification of proximal aortic dissection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):5886.

32. Nazerian P, Mueller C, de Matos Soeiro A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the aortic dissection detection risk score plus D-dimer for acute aortic syndromes: The ADvISED Prospective Multicenter Study. Circulation. 2018;137(3):250-258.

33. Song R, Xu N, Luo L, et al. Diagnostic value of aortic dissection risk score, coagulation function, and laboratory indexes in acute aortic dissection. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:7447230.

34. Harris KM, Strauss CE, Eagle KA, et al. Correlates of delayed recognition and treatment of acute type A aortic dissection: The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD). Circulation. 2011;124(18):1911-1918.

35. Neira VM, Baghaffar A, Doggett N, et al. Coagulopathy management of an acute type A aortic dissection in a patient taking apixaban. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022;36(6):1720-1725.

36. Bossone E, LaBounty TM, Eagle KA. Acute aortic syndromes: Diagnosis and management, an update. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(9):739-749d.

37. Gaudino M, Benesch C, Bakaeen F, et al. Considerations for reduction of risk of perioperative stroke in adult patients undergoing cardiac and thoracic aortic operations: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(14):e193-e209.

38. Liu L, Liu C, Li T, et al. Acute type A aortic dissection and late pregnancy: What should we do? Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;38(1):183-190.

39. Russo M, Boehler-Tatman M, Albright C, et al. Aortic dissection in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Semin Vasc Surg. 2022;35(1):60-68.

40. Zhu JM, Ma WG, Peterss S, et al. Aortic dissection in pregnancy: Management strategy and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):1199-1206.

41. [No authors listed]. Committee Opinion No. 723: Guidelines for Diagnostic Imaging During Pregnancy and Lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4):e210-e216.

42. Aranzazu-Ceballos AD, Zapata-Sanchez MM, Mendieta IA, et al. Aneurysm and subacute type a aortic dissection, in a pediatric patient with aortopathy. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;20(1):137.

43. Dean JH, Woznicki EM, O’Gara P, et al. Cocaine-related aortic dissection: Lessons from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. Am J Med. 2014;127(9):878-885.

44. Singh A, Khaja A, Alpert MA. Cocaine and aortic dissection. Vasc Med. 2010;15(2):127-133.

45. Gang Q, Lun Y, Pang L, et al. Traumatic aortic dissection as a unique clinical entity: A single-center retrospective study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(24):7535.

46. Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F, Mattiuzzi C. Systematic literature review and critical analysis of RDW in patients with aortic pathologies. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024;49(5):102476.

47. Thijssen CGE, Dekker S, Bons LR, et al. Novel biomarkers associated with thoracic aortic disease. Int J Cardiol. 2023;378:115-122.

48. Wren J, Goodacre S, Pandor A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of alternative biomarkers for acute aortic syndrome: A systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2024;41(11):678-685.

49. Chen H, Li Y, Li Z, et al. Diagnostic biomarkers and aortic dissection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23(1):497.

50. Goyal A, Jain H, Usman M, et al. A comprehensive exploration of novel biomarkers for the early diagnosis of aortic dissection. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2025;82:74-85.

51. Bima P, Nazerian P, Mueller C, et al. Performance and costs of rule-out protocols for acute aortic syndromes: Analysis of pooled prospective cohorts. Eur J Intern Med. 2025;136:63-70.

52. Morello F, Bima P, Pivetta E, et al. Development and validation of a simplified probability assessment score integrated with age-adjusted D-dimer for diagnosis of acute aortic syndromes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(3):e018425.

53. Nazerian P, Mueller C, Vanni S, et al. Integration of transthoracic focused cardiac ultrasound in the diagnostic algorithm for suspected acute aortic syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(24):1952-1960.

54. Morello F, Bima P, Castelli M, et al. Diagnosis of acute aortic syndromes with ultrasound and D-dimer: The PROFUNDUS study. Eur J Intern Med. 2024;128:94-103.

55. Hata A, Yanagawa M, Yamagata K, et al. Deep learning algorithm for detection of aortic dissection on non-contrast-enhanced CT. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(2):1151-1159.

56. Hu Y, Xiang Y, Zhou YJ, et al. AI-based diagnosis of acute aortic syndrome from noncontrast CT. Nat Med. 2025;31:3832-3844.

57. Asif A, Alsayyari M, Monekosso D, et al. Role of artificial intelligence in detecting and classifying aortic dissection: Where are we? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2025;7(3):e240353.