Pediatric Genitourinary Trauma

August 1, 2025

Executive Summary

- Common causes of straddle injuries in females include toys, playground equipment, bicycle crossbars, bathtubs, and arm chairs.

- Most straddle injuries in girls result in superficial injuries to the surface of the skin and mucosa, including bleeding, hematomas, and minor lacerations with the majority resulting in trauma to the labia.

- To examine a straddle injury in a female, position the patient either supine with the hips abducted and knees flexed in a frog-leg position or prone in a knee-chest position to optimize exposure and facilitate thorough examination.

- The best positioning for a patient presenting with an acute scrotum is supine or standing in the position of comfort. The most common physical exam findings of scrotal trauma are tenderness and swelling. Other physical exam findings may include bruising, skin loss, lacerations, hematomas, or abrasions.

- Ultrasound findings following blunt scrotal trauma include fluid collections, testicular disruption, and vascular injury. Ultrasound can reveal specific patterns that indicate a hydrocele, hematocele, testicular hematoma, testicular fracture, testicular rupture, compromised perfusion/testicular torsion, and testicular dislocation.

- Blunt testicular injuries can be managed medically or surgically, depending on clinical presentation and severity. Patients with minor injuries typically require only symptomatic care, such as cold compresses and pain management (e.g., acetaminophen or ibuprofen). However, patients presenting with significant pain or swelling should undergo immediate ultrasound imaging and microscopic urinalysis to evaluate the extent of injury.

- Identifying hair-thread tourniquet syndrome requires clinicians to have a high level of suspicion. Prompt recognition and removal is required to prevent necrosis and subsequent amputation. Patients presenting with fussiness, pain, and/or urinary symptoms should have a complete physical exam, including an exam of the genitourinary region.

- While depilatory agents have been used as first-line treatments for the removal of hair tourniquets because of their relatively painless application and ease of use, they are contraindicated in use near or on mucosal membranes.

- Concerning patterns of burn injuries for non-accidental trauma in pediatric patients include burns that are immersion-type (i.e., well-demarcated, symmetric, or circumferential), burns involving the perineum or buttocks, and burns in children younger than 5 years of age, especially when the history is inconsistent with the injury pattern or developmental capabilities of the child.

Although genitourinary trauma is uncommon, it can have devastating consequences, both physical and psychological. Clinicians need to be prepared with the knowledge needed to optimize the outcome for each child with trauma to this very sensitive area.

— Ann M. Dietrich, MD, FAAP, FACEP, Editor

By Chisom Agbim, MD, MSHS; Cherrelle Smith, MD, MS; and Mia Karamatsu, MD

Introduction

Pediatric genital trauma represents a small but clinically significant subset of emergency department visits. These injuries occur when the perineum — a complex anatomical region housing the external genitalia, urethra, and associated musculature — suffers blunt force trauma, often during childhood play or accidental falls. Although such incidents typically result in superficial injuries, such as contusions or minor lacerations, their clinical evaluation demands vigilance because of the sensitive anatomy involved and potential for deeper, more serious injuries. This review will consider the causes, evaluation, and management of genitourinary injuries in both pediatric females and males.

While most cases are non-life-threatening, they can be a source of significant distress for both patient and family and may carry long-term physical or psychological consequences if not appropriately identified and managed. Moreover, the subtle but crucial challenge lies in distinguishing accidental trauma from potential non-accidental causes, such as abuse — underscoring the need for comprehensive history taking, meticulous physical examination, and, when indicated, multidisciplinary collaboration. For emergency care providers, accurate assessment of injury severity is paramount. This includes recognizing when further evaluation is warranted and understanding the indications for surgical consultation. With thoughtful evaluation, timely intervention, and compassionate communication, pediatric emergency teams can ensure both optimal clinical outcomes and supportive care for these young patients and their families.

Female Straddle Injuries

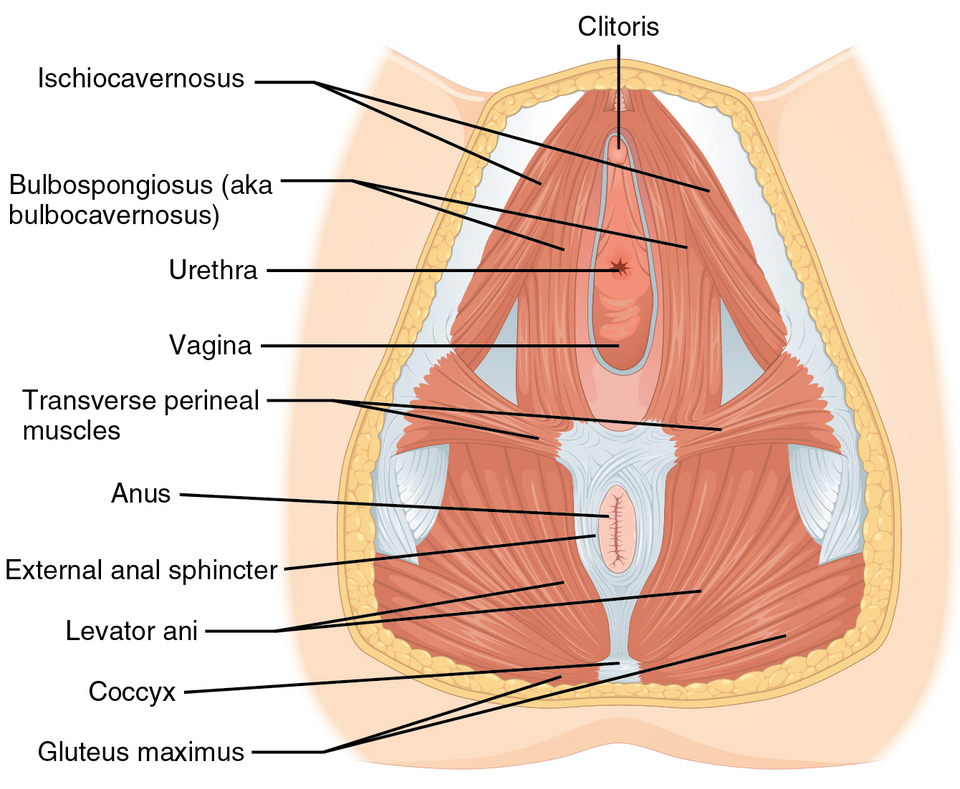

Genitourinary trauma occurs when the perineum is injured by a fall or impact onto a blunt object. The perineum is a diamond-shaped region at the base of the pelvis that is divided into the urogenital triangle anteriorly and the anal triangle posteriorly. It contains the external genitalia, the urethra, and various muscles that support urinary and reproductive functions as well as the anal canal and associated sphincters. (See Figure 1.) The area is supplied by the internal pudendal artery and innervated primarily by the pudendal nerve, making it clinically significant for functions such as urination and defecation.

Figure 1. Female Perineum |

|

Source: Openstax. File:1116 Muscle of the Female Perineum. Published Nov. 23, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1116_Muscle_of_the_Female_Perineum.png. CC BY 3.0. |

Female straddle injuries occur when an individual falls onto the perineum, which collides with a blunt object with the force generated from their body. The straddle mechanism can result in injuries to the external genitalia, including the vulva and perineum. The hymen and vagina rarely are injured, although it is possible depending on the force of the impact.

Epidemiology

Pediatric genital injuries account for approximately 0.6% of all pediatric injuries.1 Accidental pediatric genital injuries account for 0.2% to 0.8% of reported childhood trauma incidents.1-3 Pediatric genital injuries mostly occur between the ages of 4 to 9 years, with the average age being 5 years in both male and female patients.1-3 Straddle injuries in children typically are non-life-threatening, but they can cause psychological trauma and long-term complications if they are unrecognized or improperly treated.

Etiology

Pediatric straddle injuries are caused mostly by accidental falls while straddling an object.4 Risk factors for straddle injuries include activities that increase the likelihood of direct perineal trauma, such as straddling fences, bathtubs, or bicycle crossbars. Inadequate supervision also increases the risk of these injuries.

Common causes involve toys, playground equipment, bicycle crossbars, bathtubs, and arm chairs.5 A review of patients younger than 16 years of age with accidental genital trauma, excluding sexual and obstetric-related injuries, over two decades found that 70.5% of patients sustained injuries through straddle mechanisms. Similar studies also have found that straddle injuries are the most common mechanism for accidental genital trauma in females.2,6 Playground injuries are a common source of pediatric genitourinary trauma. The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System found that, from 2010 to 2019, playground equipment accounted for 27,738 emergency department (ED) visits in patients younger than 18 years of age, representing approximately 1.3% of all injuries sustained at playgrounds.7 Another study by Takei found that common consumer products associated with pediatric accidental genital injuries were furniture, exercise equipment, and bicycles, which echoed similar findings in other countries.8

Pathophysiology

Most straddle injuries result in superficial injuries to the surface of the skin and mucosa, including bleeding, hematomas, and minor lacerations. The majority of straddle injuries result in trauma to the labia, with injuries of the perineum occurring in approximately 20% of patients.9 Most objects causing straddle injuries would not result in penetration above the pelvic floor.10 It is rare for injuries to extend into the vagina, although deeper injuries have been reported. Straddle injuries are associated with bleeding secondary to trauma of the internal and external pudendal artery and vein. While there may be copious bleeding initially, in most cases, the bleeding is controlled upon presentation to care.

Clinical Features

Straddle injuries are most commonly identified by a straightforward history and exam. Symptoms of accidental straddle injuries include pain, bleeding, and difficulty urinating because of injury with subsequent swelling to the urethra. A history should include information on the timing of injury and how the injury was sustained. Clinicians also should inquire whether patients have been able to urinate and whether hematuria was present. It is important to note whether the history is consistent with the presenting injury. If the mechanism of injury is not consistent with the physical findings, further investigation is necessary to rule out non-accidental trauma.

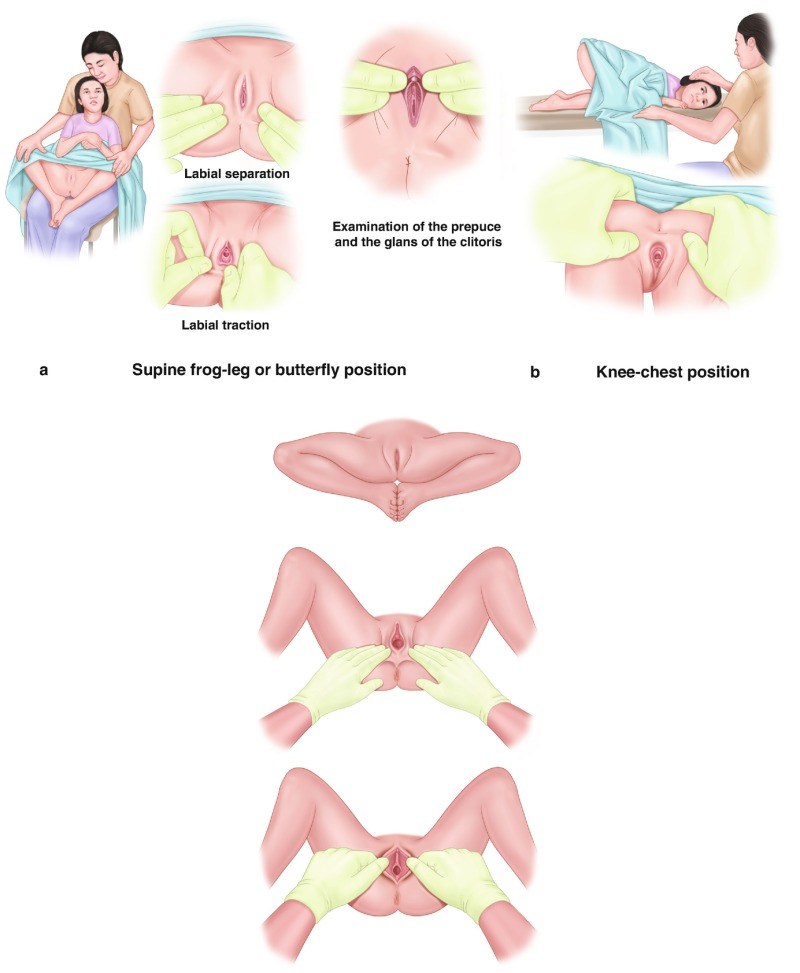

A thorough exam is critical to avoid missing injuries to the genitourinary tract, which may lead to delays in repair and subsequent urethral or vaginal stenosis and chronic fissures.2,11 A careful examination should be performed for non-obvious injuries, injuries with a concerning history, when the exam is obstructed because of bleeding or swelling, or when further physical or psychological trauma may be introduced. Providers should ensure that a chaperone is present during the examination and remain mindful of any cultural or religious beliefs that may influence the patient’s comfort level, preferences, and overall experience during evaluation and treatment.12,13 Evaluation of straddle injuries begins with proper visualization of the affected area. Position the patient either supine with the hips abducted and knees flexed in a frog-leg position or prone in a knee-chest position to optimize exposure and facilitate thorough examination. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2. Female Pediatric Genital Examination Postions |

|

Source: Abdulcadir J, Sachs Guedj N, Yaron M, eds. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in Children and Adolescents: Illustrated Guide to Diagnose, Assess, Inform and Report [Internet]. Published 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK592366/figure/ch3.Fig1/. CC BY 4.0. |

The non-estrogenized prepubertal female genital tissues are friable and lack distensibility, leading to notable bleeding even with minor trauma. Bruising, bleeding, swelling, and lacerations are common findings of straddle injuries. Some mechanisms of accidental trauma, including crush, shear, and penetration, do not consistently result in persistent external bleeding.2 Hymenal damage suggests deeper injury and should be thoroughly evaluated in a more controlled environment.

A critical consideration in the management of straddle injuries is determining whether examination under anesthesia (EUA) routinely should be performed for all patients. Some experts have argued that an EUA should be performed for all patients who have accidental genitourinary trauma because of the possibility of missed findings, leading to further complications.14-16 One study found that concordance between the exam performed in the ED and the EUA to be as low as 24%, with a much greater extent of injury identified with EUA.14 Because of this discordance in findings, it has become common practice to perform an EUA in the operating room for all patients with extensive genital injury to allow for a complete evaluation of the extent of injury with surgical repair performed as necessary.

Most studies have shown that injuries sustained from accidental straddle injuries could be managed without surgical intervention. Furthermore, the cost of care for ED repair was less than two-thirds that of surgical repair in the operating room.17 This has led experts to recommend more selective use of EUA, given the lower resource demands and positive outcomes with expectant management.9 A 2002 study by Scheidler et al examined common mechanisms of blunt perineal trauma in female pediatric patients and sought to identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit from EUA. The authors reviewed data from 358 pediatric patients recorded in the Pennsylvania Trauma Outcome Study database between 1993 and 1997 and found that children younger than 10 years of age required surgical repair of perineal injuries more frequently than older children.

Additionally, injuries resulting from falls, assaults, or playground-related incidents were more likely to require surgical intervention compared to injuries from other mechanisms. This prompted the authors to recommended considering EUA for pediatric patients who sustain perineal injuries from falls, assaults, or playground-related activities.18 Some retrospective studies have found children injured by falls and bicycles are the most common mechanisms and children aged 4 to 9.5 years are the age group most associated with operative intervention in blunt injury patients.4

Some authors have developed specific criteria to guide the decision of when to perform an EUA.2,3,19 (See Table 1.) One study advocated for EUA when the patient’s distress limits the evaluation, when extensive injuries are obvious or suspected, or when evaluation with conscious sedation or general anesthesia is appropriate to ensure a complete examination and correlation with the reported mechanism of injury.9 Spitzer et al reviewed their experience at a pediatric referral center and identified factors associated with the need for sedation in the ED or operative EUA following unintentional female genital trauma. These factors included older patient age, transfer from another facility, laceration injury, hymenal injury, larger injury size, and penetrating injury.3 Another study by Dowlut-McElroy et al in 2002 found that factors associated with the need for EUA included older age; transfer from another institution; penetrating injuries; injuries involving the hymen, vagina, urethra, or anus; and injuries larger than 3 cm in size.2

Table 1. Indications to Perform an Examination Under Anesthesia2,3,9,19 |

|

Diagnostic Studies

Straightforward straddle injuries do not require imaging or laboratory studies. A 2002 study on patients with isolated straddle mechanism injuries found that radiologic imaging did not add diagnostic value for female pediatric patients with blunt straddle injuries.20 When additional injury is suspected based on the mechanism or physical exam findings, further imaging or diagnostic evaluation may be performed alongside an EUA to identify occult injuries. For instance, urinalysis may serve as an initial diagnostic modality; the presence of hematuria (> 20 red blood cells per high-power field) can be suggestive of genitourinary tract injury following blunt trauma.

Differential Diagnosis

Other diagnoses that can mimic the presentation of a straddle injury include Streptococcus infections, urethral prolapse, lichen sclerosus, vulvovaginitis, vaginal foreign bodies, and minor self-inflicted trauma. Streptococcal infections typically present with redness, pain, swelling, and bright red lesions, which may resemble acute minor trauma. Urethral prolapse presents with discomfort, dysuria, and visible tissue at the vaginal introitus, which may be mistaken for trauma. Lichen sclerosus can mimic a straddle injury by causing symptoms such as pain, bleeding, swelling, and irritation in the genital area, along with the presence of white patches or lesions that may resemble abrasions or trauma. Minor self-inflicted trauma can cause irritation, excoriations, or bleeding, which may mimic a straddle mechanism. The differential diagnosis for female straddle injuries includes non-accidental trauma, penetrating trauma, and urethral injuries. Injuries sustained from sexual abuse most commonly are located in the posterior fourchette, hymen, and vagina and usually are symmetric in nature. Sexual trauma should always be considered in the initial differential of straddle injuries, especially if the history is inconsistent or vague and when concerning physical findings such as injuries to the posterior fourchette and hymenal disruption are noted on exam.9 Penetrating trauma should be suspected based on a history of impalement or if puncture wounds are identified on exam. The inability to void or the presence of hematuria should prompt providers to consider a possible urethral injury.

Management

Initial management should prioritize pain control, anxiolysis, and hemostasis. Hemostasis typically can be achieved by applying gentle, direct pressure to the bleeding site with sterile gauze. Involving caregivers, using gentle distraction techniques, or engaging child life specialists can help reduce patient anxiety and improve the success of the bedside examination. Providers should exercise caution during the exam to avoid causing additional injury or discomfort. If dried blood obstructs visualization, gently irrigating the area with warm, sterile water at low pressure can help clear the field and facilitate a thorough evaluation. Patients who have ongoing bleeding despite initial attempts at hemostasis, extensive injuries, lacerations that cannot be fully visualized during examination, inability to pass urine, or suspected non-accidental genitourinary trauma require prompt consultation with a pediatric gynecologist or pediatric surgeon. If abuse is suspected, the child protection team — including social workers, law enforcement, and medical professionals trained in forensic examinations — should be involved as soon as possible. Severe injuries that cannot be adequately evaluated or managed comfortably in the ED setting should be scheduled for EUA by a subspecialist experienced in pediatric gynecologic care. When suturing is necessary, the procedure should always be performed by a pediatric gynecologist or another specialist with equivalent pediatric gynecologic training to minimize the risk of future complications.

Straddle injuries may present with vulvar hematomas, which may require surgical drainage. The pressure exerted by a large hematoma can compromise blood flow to the surrounding tissues, potentially leading to tissue damage and necrosis if it is not promptly managed. According to a 2002 study by O’Brien et al, surgical intervention typically is reserved for larger hematomas or those causing significant symptoms. Studies have shown that most hematomas up to 3 cm in premenarchal patients and up to 6 cm in postmenarchal patients can be managed conservatively.12,13,21 However, hematomas larger than 5 cm to 6 cm, those causing severe pain, hemodynamic instability, or those that do not resolve with conservative management may require drainage.12 A pediatric gynecologist or a medical specialist with equivalent training should perform the surgical drainage of a vulvar hematoma following a straddle injury, especially in cases of large, symptomatic, or non-resolving hematomas. This recommendation is based on the specialized expertise required to effectively manage these injuries as well as the necessity for advanced knowledge of female genital anatomy and trauma management.

At present, there is no standardized method for evaluating the severity of straddle injuries. However, a recent study by Bergus et al introduced a novel grading system and management algorithm for these injuries. In their system, injuries are graded from 1 to 6 based on the extent of visible genital trauma and the anticipated need for surgical repair. Their proposed algorithm emphasizes bedside examination and repair under procedural sedation in the ED setting, potentially reducing the need for general anesthesia and operating room resources. Although recently published, this approach provides a promising framework for the evaluation, management, and efficient use of resources in treating pediatric straddle injuries.22

Additional Aspects

Medical complications from straddle injuries are uncommon but may include infection, scar formation, chronic pain, tissue necrosis, and persistent urinary problems.3,23-27 Early and appropriate intervention can help mitigate some of these long-term effects. Management of these complications often requires a multidisciplinary approach, including urologists, gynecologists, and sometimes reconstructive surgeons, to address both the physical and psychological impacts of the injury.

Given their similarities to non-accidental trauma, medico-legal and ethical considerations are particularly important in cases of pediatric straddle injuries. Providers must obtain a thorough history and remain vigilant for inconsistencies or red flags that may raise suspicion of sexual abuse. At the same time, clinicians should avoid prematurely anchoring to a diagnosis of non-accidental trauma when evidence suggests otherwise, since false accusations can cause significant harm to children, caregivers, and families. If in doubt, providers should consult a skilled professional, such as a child abuse specialist, for further guidance.

Disposition

The majority of patients that present for care of straddle injuries are discharged home with supportive care.1 Patients who have minor injuries and are able to pass urine are eligible for discharge from the ED with instructions regarding symptomatic care and follow up with their primary care provider as needed. Acetaminophen and ibuprofen typically provide adequate analgesia for pain associated with straddle injuries.

Small and superficial lacerations will heal well on their own. Ensuring proper hygiene of the affected area and applying a barrier ointment, such as petroleum jelly, can help lower the risk of infection and support the healing process. The application of petroleum jelly forms a protective barrier that shields the wound from urine exposure, thereby minimizing discomfort during urination.

Hematomas up to 3 cm in premenarchal patients and up to 6 cm in postmenarchal patients can be managed conservatively.12 This includes the application of cold compresses for 20 minutes every two hours for the first 24 to 48 hours, which can help with reducing pain and edema. Dysuria may be alleviated by urinating in warm water, such as while sitting in a bath, or by applying petroleum jelly to the affected area (as previously noted) until symptoms subside. Patients with extensive injury or those who require an EUA may require hospital admission or transfer to a pediatric specialty center. Depending on the extent of injury, patients may be discharged home following EUA and repair, or they may require further observation and management in the hospital. Admission criteria and hospital resources vary based on location.

Female Straddle Injury Summary

Female straddle injuries typically occur when the perineum impacts a blunt object, often caused by accidental falls onto playground equipment, bicycles, or furniture. These injuries most commonly affect girls aged 4-9 years and usually result in superficial trauma to the vulva and perineum. Patients typically present with pain, bleeding, swelling, and dysuria. In most cases, conservative management with appropriate analgesia and local wound care is sufficient.

However, the presence of extensive tissue damage, persistent hemorrhage, urinary retention, or clinical suspicion of abuse warrants further evaluation through EUA in the operating room to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate intervention. Providers should remain vigilant for signs of non-accidental trauma and promptly involve child protection teams when indicated. Complications are rare but may include infection, scarring, and ongoing urinary issues.

Scrotal Injuries

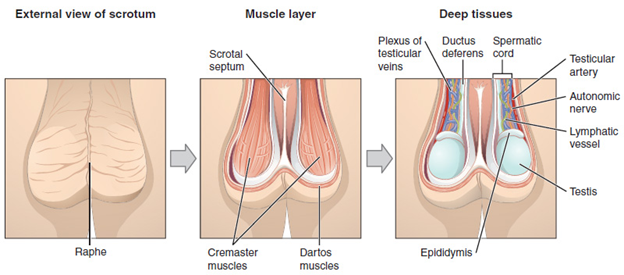

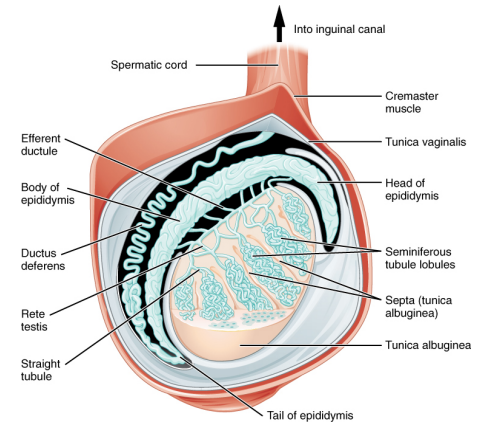

Scrotal trauma refers to injuries sustained through blunt or penetrating mechanisms affecting the scrotum, potentially causing damage to its internal structures and contents. The scrotum is a pouch of skin containing the testicles. It is divided into two compartments, each housing one testicle, along with the surrounding tunica vaginalis and the epididymis. The spermatic cord extends from the inguinal canal to the testicle and plays a crucial role in supporting the testis and providing it with blood supply. The cremaster muscle surrounds the spermatic cord and helps regulate the position of the testes in relation to the body. (See Figures 3 and 4.)

Figure 3. Scrotum |

|

Source: Openstax. OpenStax AnatPhys fig.27.3 — scrotum and testes — English labels. https://assets.openstax.org/oscms-prodcms/media/documents/Anatomy_and_Physiology_2e_-_WEB_c9nD9QL.pdf. CC BY 4.0. |

Figure 4. Testis |

|

Source: Openstax. OpenStax AnatPhys fig.27.4 — anatomy of the testis — English labels. https://assets.openstax.org/oscms-prodcms/media/documents/Anatomy_and_Physiology_2e_-_WEB_c9nD9QL.pdf. CC BY 4.0. |

Epidemiology

Scrotal injuries represent a small proportion of traumatic injuries in the pediatric population. Non-sexual trauma to the male external genitalia occurs most commonly in toddlers and small children (ages 2-5 years) and school-aged children (ages 6-12 years) as a result of sport accidents, kicks, and falls.28 One retrospective study examined the epidemiology of sports-related testicular trauma presenting to an ED in the United States between 2012 and 2021. Using the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System Database, the authors found ages 10-14 years and 15-19 years as the most common age groups affected. The majority of injuries occurred during participation in basketball, football, soccer, and baseball.29 The incidence of scrotal injuries has remained relatively stable over recent years despite ongoing safety measures. Isolated scrotal injuries are non-life-threatening. However, they can result in long-term complications associated with reproductive function, micturition, and defecation.

Etiology

Because the scrotum sits outside the body and is not protected by muscle or bone, it is more susceptible to injury. Trauma to the scrotum usually occurs from straddle injury pattern, direct blunt force, or penetrating injury. Blunt force injuries are caused by an impact or strike whereas penetrating injuries are due to a sharp object piercing the scrotum. While penetrating injuries can occur, they are particularly rare, especially in the pediatric population.

Pathophysiology

Injuries involving the scrotum and its contents typically result from direct blunt trauma, or rarely, from a penetrating mechanism caused by an accidental fall followed by the impalement of the scrotum by an object. Scrotal and penile injuries, including lacerations and contusions, frequently occur following straddle-type mechanisms — particularly those associated with playground equipment-related accidents.28 These injuries are the result of a sudden compressive force to the scrotum. The force of this type of injury also can cause testicular contusion, hematoma, or rupture. Such trauma may cause tearing of the tunica albuginea, which can lead to extravasation of blood and testicular parenchyma. Additionally, hematomas or hydroceles may develop because of the accumulation of blood or fluid around the testis. Testicular torsion also can occur, compromising blood flow and leading to ischemia if not promptly recognized and treated.

Clinical Features

Patients with isolated scrotal trauma generally will present with a non-toxic appearance. Vital signs may be reflective of pain, including tachycardia and an elevated blood pressure. The best positioning for a patient presenting with an acute scrotum is supine or standing in the position of comfort. The most common physical exam findings of scrotal trauma are tenderness and swelling. Other physical exam findings may include bruising, skin loss, lacerations, hematomas, or abrasions. Pertinent associated clinical symptoms may include abdominal pain, dysuria, nausea, and vomiting.30 Physical examination often is impeded by patient discomfort and significant soft tissue edema, which can obscure critical anatomical landmarks and limit a thorough assessment. Examinations may be improved with prompt administration of analgesics, employment of agents for anxiolysis, use of distraction techniques, and assistance of a child life specialist, assuming one is available.

Diagnostic Studies

Clinical evaluation of a scrotal injury may be difficult because of swelling and/or pain. When a physical examination is limited, ultrasonography — which offers diagnostic imaging without radiation exposure — should be used to assess the underlying injury. According to the American Urological Association Guidelines, scrotal ultrasonography should be performed for most patients having findings suggestive of testicular rupture — scrotal ecchymosis, swelling, and difficulty identifying the contours of the testicle on examination.31

Ultrasound findings following blunt scrotal trauma include fluid collections, testicular disruption, and vascular injury.32 Ultrasound can reveal specific patterns that indicate a hydrocele, hematocele, testicular hematoma, testicular fracture, testicular rupture, compromised perfusion/testicular torsion, and testicular dislocation.19

Scrotal hematomas are a common finding that appear as focal thickening of the scrotal wall or fluid collections within the scrotal wall. Hydroceles and hematoceles appear as fluid collections that occur in the potential space between the two layers of the tunica vaginalis. A large testicular hematoma can be confused with a hematocele if the testicle or surrounding tunica albuginea cannot be visualized by ultrasound.17 A testicular rupture appears as a hemorrhage and extrusion of testicular contents into the scrotal sac with discontinuity of the echogenic tunica albuginea.32 Testicular fracture, a disruption of the testicular parenchyma, is uncommon and distinguished from testicular rupture by an intact tunica albuginea. Ultrasound features of testicular rupture include discontinuity of the tunica albuginea, alteration in testicular echogenicity, irregular testicular contour, and testicular fracture.17 Torsion of the spermatic cord with compromised testicular blood flow is indicative of testicular torsion.

One study by Guichard et al demonstrated the accuracy of ultrasound for diagnosing scrotal injuries in 33 patients who underwent surgical exploration and compared the accuracy for the following findings in Table 2.16

Table 2. Sensitivities and Specificities of Ultrasound for Scrotal Diagnoses16 |

Hematocele

Tunica Albuginea Breach

Testicular Rupture

Testicular Hematoma

Scrotal Edema

Testicular Avulsion

Epididymis Injury

No Scrotal Injury

|

The study also found that ultrasound for epididymis injuries was poor (sensitivity 57%, specificity 85%, positive predictive value 50%, negative predictive value 88%) and that epididymis injuries were misdiagnosed by ultrasound examination.16

Differential Diagnosis

Scrotal trauma usually is diagnosed with a straightforward history of trauma. The differential for blunt force injuries to the scrotum include traumatic testicular torsion, testicular rupture, testicular hematoma, testicular avulsion, tunica albuginea breach, epididymitis, hydrocele or hematocele, traumatic orchitis, scrotal hematoma, scrotal laceration, and scrotal abrasion. Testicular torsion usually presents when the affected testicle found in a high-riding position with accompanied tenderness and possible scrotal swelling and erythema. The exam may also reveal an absent cremasteric reflex. Findings for testicular rupture include pain, swelling, ecchymosis, and tenderness of the affected testicle with a possible palpable defect in the testicular surface. Scrotal hematomas present with painful swelling and discoloration, with palpable mass or fluctuant area indicating the presence of blood accumulation. Epididymitis will present with tenderness and swelling of the affected epididymis which may be palpable as a firm, enlarged structure behind the testicle. Epididymitis also may present with a Prehn’s sign, defined as the relief of pain with elevation of the scrotum. On physical examination, a hydrocele presents as a smooth, non-tender, and swelling in the scrotum that transilluminates, while a hematocele typically appears as a tense mass that may be tender and associated with bruising or discoloration of the scrotal skin that does not transilluminate, indicating the presence of blood within the scrotal sac. With traumatic orchitis, the affected testicle may be swollen, tender, and painful to palpation, with possible bruising or discoloration of the scrotal skin. There also may be associated signs of inflammation, such as warmth and erythema in the scrotal area. Scrotal lacerations and abrasions present with bleeding and discoloration of the scrotum, with interruption of the superficial skin and possibly deeper structure.

Penetrating scrotal or testicular injuries can result in complications such as retained foreign bodies, urethral injury, spermatic cord damage, associated inguinal or bowel injuries, and delayed infections or abscess formation. Providers should carefully assess whether the reported mechanism of injury aligns with clinical findings, since scrotal injuries also may indicate non-accidental trauma or sexual abuse. If abuse is suspected, consultation with a child protection team is essential for further evaluation and management.

Management

Blunt testicular injuries can be managed medically or surgically, depending on clinical presentation and severity. Patients with minor injuries typically require only symptomatic care, such as cold compresses and pain management (e.g., acetaminophen or ibuprofen). However, patients presenting with significant pain or swelling should undergo immediate ultrasound imaging and microscopic urinalysis to evaluate the extent of injury. If ultrasound is unavailable or the results are inconclusive, surgical consultation is indicated and surgical exploration may be necessary.33 Prompt consultation with urology is essential for suspected testicular or urethral injuries. It commonly is taught that the optimal time window for salvaging a torsed testicle is approximately six to eight hours. Although testicular survival has been reported beyond this timeframe, patients presenting with testicular pain or scrotal injury should be identified promptly and aggressively managed to maximize the likelihood of testicular preservation.34

Management of scrotal injuries depends on the extent of injury. Direct pressure should be applied to the bleeding site to control hemorrhage. Elevating the scrotum and applying ice packs also can aid in reducing swelling and bleeding. Isolated superficial lacerations may be repaired in the ED by a urologist or a provider with appropriate urological expertise, often under procedural sedation. Findings on ultrasound that prompt urological consultation include penetrating scrotal trauma with wounds extending into or through the dartos layer, testicular rupture, large testicular hematoma, hematocele, large scrotal hematoma, ultrasonographic findings of testicular compression or decreased blood flow, testicular dislocation, traumatic testicular torsion, and scrotal avulsion. In addition, penile deformity, pain, and/or blood at the penile meatus also are indications for urologic consultation in children with scrotal trauma.35

Additional Aspects

While many scrotal injuries result from accidental trauma that often is unavoidable, educating male athletes aged 10 to 19 years on the importance of wearing protective equipment, such as an athletic cup, may help reduce the risk of serious genitourinary injuries, particularly in contact sports. A survey of young male athletes indicated that 18% had sustained a testicular injury during sports activities, yet only 12.9% reported using athletic cups. These findings underscore the low use of protective gear in this population, which likely contributes to the continued incidence of such injuries.36 Awareness of the potential for injury can lead to more cautious behavior during high-risk activities.

Unrecognized scrotal injuries, delays in treatment, and loss to follow-up can result in significant long-term complications. These complications can include, but are not limited to, testicular atrophy, infertility, chronic pain, infection, and abscess formation. Prompt identification and timely intervention are critical to optimize patient outcomes and prevent lasting morbidity.

Disposition

Patients identified as having minor scrotal injuries that do not require surgical or procedural intervention can be safely discharged home with supportive care measures, including analgesics, scrotal elevation with supportive underwear, and application of cold compresses. In cases involving more extensive or complex injuries, management should be individualized based on findings from the physical examination and diagnostic evaluation. A consultation with a pediatric urologist is recommended to determine the most appropriate treatment approach.

Summary

Scrotal trauma encompasses injuries to the scrotum and its contents, often resulting from blunt or penetrating forces, and is most prevalent in school-aged boys and adolescents because of sports and accidents. The scrotum, which houses the testes, is particularly vulnerable because of its external location and lack of protective structures. Clinical presentation typically includes pain, swelling, and potential bruising, with diagnostic challenges arising from discomfort and swelling. Ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality to assess injuries, revealing conditions such as hematomas, ruptures, and torsions. Management varies based on injury severity, with minor cases often treated with pain relief and supportive care, while significant injuries may necessitate surgical intervention and urological consultation. Complications can include retained foreign bodies and infections, and careful evaluation is essential to rule out non-accidental trauma.

Other Considerations

Hair Tourniquet Syndrome

Hair-thread tourniquet syndrome (HTTS) or hair tourniquet syndrome refers to a condition in which a body part becomes constricted because of a hair or hair-like thread tightly constricting it.37 HTTS commonly involves the fingers and toes, although genital structures also are common locations.38

HTTS of genitalia begins when the penis or clitoris becomes entangled in a thin hair or hair-like thread, usually from clothing. Local edema of the affected appendage ensues, following the tight wrapping of the thread, which reduces blood flow to the area. If the tourniquet is not removed promptly, it can lead to local ischemia followed by tissue necrosis of the affected body part. The mechanism of injury is presumed to involve the impedance of lymphatic drainage by the constricting hair or thread, which triggers a course of lymphedema, venous outflow obstruction, and eventual arterial inflow obstruction process occurring over hours to months if left undetected.37

There are a few cases of pediatric genital HTTS described in the literature. A systematic review of cases of genital HTTS in pediatric patients younger than 21 years of age from 1951-2020 found 38 cases in females and 147 cases reported in males, with an average age in females of 9.1 years and 5.1 years in males.39 The study found that the most commonly involved body parts were clitoris and labia minora in females and the penis and urethra in males. Males most commonly presented with edema and urinary symptoms, whereas females most commonly presented with edema and pain.39 In females, genital pain was sometimes associated with wide-base gait or dysuria.40 In males, young infants presented with irritability and crying, often associated with swelling, while older children presented with pain and swelling.40

Identifying HTTS requires clinicians to have a high level of suspicion. Prompt recognition and removal is required to prevent necrosis and subsequent amputation. Patients presenting with fussiness, pain and/or urinary symptoms should have a complete physical exam, including an exam of the genitourinary region.

Hair tourniquets are identified by swelling of the area distant to a local area of constriction. Once identified, the tourniquet should be removed as soon as possible. While depilatory agents have been used as first-line treatments for the removal of hair tourniquets because of their relatively painless application and ease of use, they are contraindicated in use near or on mucosal membranes. Because of this, depilatory agents may be used on male penile tourniquets, although care should be taken to avoid prolonged application to the area and further skin irritation. Female genital tourniquets require more invasive means for removal because of their proximity to mucosal membranes. Removal usually requires manual removal with a dorsal longitudinal incision for tourniquet release. This can be performed using forceps, scissors, or a scalpel blade.41,42 Most patients will require sedation and pain control, given the sensitivity of the location and pain from removal. Many tourniquet removals can be completed in an urgent care or ED setting. Depending on the extent of tissue edema or necrosis, removal and subsequent follow-up may require coordination with a pediatric urologist or gynecologist.

Retained Vaginal Foreign Body

A vaginal foreign body is defined as the introduction of an object that is not naturally found in the vagina. This condition is most commonly observed in pediatric cases, particularly among prepubertal girls aged between 3 and 10 years.43-45 Studies have shown that the most frequently recovered vaginal foreign bodies in children include toilet paper; small, hard objects (such as beads or toy parts); and, less commonly, batteries.42,46 Batteries pose a significant risk because of their potential to cause tissue injury leading to the formation of vesicovaginal fistulas (between the bladder and the vagina) and rectovaginal fistulas (between the rectum and the vagina). Vaginal foreign bodies usually are accidentally self-inflicted, although providers should always consider the possibility of sexual abuse.

Providers should have a high level of suspicion for a vaginal foreign body, since history-taking has been seen to identify the presence of a foreign body in only 10% to 50% of pediatric cases.43,46 The typical clinical presentation of a vaginal foreign body includes vaginal discharge or vaginal bleeding. A vaginal foreign body should be suspected in a pediatric patient who presents with persistent or recurrent vaginal discharge (especially if it is foul-smelling or blood-stained), unexplained vaginal bleeding, or chronic vulvovaginitis that is unresponsive to standard therapy.43-47

In some instances, healthcare providers may be able to identify a vaginal foreign body through an external examination. However, an EUA in collaboration with a pediatric gynecologist is recommended for removal of vaginal foreign bodies that are not easily visualized or when a patient is not able to tolerate a bedside exam. Immediate removal is imperative for suspected or confirmed batteries or when there is evidence of tissue injury, since these can rapidly cause necrosis or perforation. Despite the prevalence of this issue, there are currently no national guidelines established to standardize the management of vaginal foreign bodies. Instead, management has relied on retrospective reviews and individual case studies, highlighting the need for more comprehensive guidelines in the future.

Zipper Injures

A zipper injury refers to the entrapment and injury of skin or soft tissue within the mechanism of a zipper. The injury typically occurs when the skin becomes caught between the interlocking teeth or within the slider of the zipper, resulting in a crush or laceration injury. Zipper injuries most commonly involve the genitalia, especially the penile tissue or foreskin skin in males, and represent nearly one-fifth of penile-related injuries in the United States.48

The diagnosis of a zipper injury typically is straightforward, involving the collection of a direct history from the patient or caregiver, followed by a physical examination for direct visualization of the injury. During the examination, the diagnosis becomes apparent when the examiner observes tissue, most commonly the skin of the penis or scrotum, trapped between the teeth or within the slider of the zipper. This entrapment often is accompanied by localized pain, swelling, and (in some cases) bleeding or edema at the site of the injury.

Management focuses on safe and timely release of the entrapped tissue to minimize further trauma and prevent complications, such as tissue necrosis and infection. Management strategies are variable for zipper injuries. Initially, it is crucial to provide adequate analgesia, which can be administered orally, topically, or locally, to ensure the patient’s comfort during the procedure. One of the first steps in managing the injury is to cut the fabric surrounding the zipper. This action helps to prevent additional traction and pulling on the affected tissue, which could exacerbate the injury. To release the entrapped skin, one common technique involves cutting the median bar of the zipper pull using bone or wire cutters.49 Another approach is to apply a lubricant, such as mineral oil, to the area, and attempt to unzip the zipper gently. If this method proves unsuccessful, other techniques can be employed — for example, by wedging a screwdriver or wire cutter between the faceplates.50 Alternatively, clinicians can promote separation with torque forces by squeezing the top faceplate with pliers.48-52 In cases where these methods do not resolve the issue, more invasive procedures (following consultation with pediatric urology or pediatric surgery) may be necessary. An elliptical incision or even circumcision might be required to free the entrapped skin and ensure proper healing.53 These advanced interventions typically are reserved for refractory cases where less invasive techniques have failed to achieve the desired outcome.

Burn Injuries

Burn injuries to the genitalia and perineum are uncommon. However, they disproportionately affect children compared to adults. Data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System has shown that children 0-2 years of age had the highest prevalence of genital burns and that, for children younger than 5 years old, the majority of burns occurred with hot water in the bathroom. Among patients aged 6 to 12 years, scald burns most often were caused by hot foods, followed by hot water and hot beverages.54

Burn injuries to the genitalia rarely occur in isolation. Genital burns often occur with more extensive total body surface area burns, especially in children younger than 5 years of age.55,56 Providers should take a careful history, paying special attention to the timing, mechanism and location of the reported injuries. Concerning patterns of burn injuries for non-accidental trauma in pediatric patients include burns that are immersion-type (i.e., well-demarcated, symmetric, or circumferential), burns involving the perineum or buttocks, and burns in children younger than 5 years of age, especially when the history is inconsistent with the injury pattern or developmental capabilities of the child. Additionally, burns in the genital or perineal area that are isolated (not part of a larger burn pattern), or that occur in non-ambulatory children, are particularly concerning for abuse.

In situations where the history provided is unclear, the pattern of injury raises suspicions of abuse, or the mechanism of injury does not align with the patient’s injuries, it is imperative to involve social work and Child Protective Services (CPS). These professionals play a crucial role in assessing and addressing potential cases of child abuse or neglect. Furthermore, healthcare providers have a responsibility to report all instances of burn injuries where caregivers have failed to seek timely medical evaluation to CPS. Such cases particularly are concerning because they may indicate child neglect, which requires immediate attention and intervention. This is especially important to providers because half of the children who experience abuse-related burn injury will sustain recurrent abuse, and 30% of children with burn abuse eventually die unless intervention occurs.57

Additionally, it is noteworthy that burns resulting from neglect occur at a rate nine times higher than those caused by direct abuse.58 This stark contrast underscores the necessity for healthcare providers to thoroughly evaluate the circumstances surrounding every burn injury in a child. By doing so, providers can ensure that appropriate measures are taken to protect the child and prevent further harm.

Burn injuries involving the genitalia in children are classified as major injuries because of their potential for significant functional and cosmetic impairment. Recognizing the complexity and severity of these injuries, the American Burn Association, along with recent consensus guidelines, have specifically listed burns to the genitalia and perineum as a criteria for referral to a burn center.59-61 This designation underscores the necessity for specialized multidisciplinary care to address the unique challenges these injuries present.

Upon identifying such injuries, healthcare providers promptly should contact their local pediatric burn center. These centers are equipped with the expertise and resources needed to provide comprehensive care and can offer valuable guidance on the immediate management of the injury and assist in coordinating the transfer of the patient when appropriate. This collaboration is crucial in delivering the specialized care required to minimize long-term functional and cosmetic consequences, thereby enhancing the child’s recovery and quality of life.

Female Genital Mutilation or Cutting

Female genital mutilation or cutting (FGM/C), sometimes referred to as “female circumcision,” refers to the removal of parts or the entirety of the external female genitalia for non-medical reasons. The practice has been banned in many parts of the world. The majority of the practice takes place in African countries, with more than 144 million cases, followed by more than 80 million cases in Asia, and more than 6 million cases in the Middle East.62 The majority of FGM/C occurs in 30 African and Middle Eastern countries, with the highest prevalence in Egypt, Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti, Mali, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Eritrea.63 FGM/C occurs at any age from infancy to adolescence. The degree also can vary from minor nicking to draw blood to the most severe form, infibulation, where the cut edges of the labia are sewn together, and must be reopened for sexual intercourse or childbirth.62

It is important to note that the practice of FGM/C is not standardized, and physical findings may overlap between types and subtypes. Exam findings of FGM/C have been classified by the World health Organization based on the degree of alteration of structures.64 The Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center at Arizona State University also has provided a visual reference for structures according to this classification system.65 If FGM/C is suspected, providers should approach the topic with cultural sensitivity and obtain a detailed history, including details of the location of, timing of, and who was involved in the procedure. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends against the use of the of the word “mutilation” when discussing FGM/C with patients and caregivers because it is potentially inflammatory, difficult to translate, and may not be understood by patients and caregivers. Prompt consultation of social work and pediatric gynecology is recommended for obtaining further history in addition to diagnosis and management of confirmed cases.

Conclusion

This review highlights the critical need for clinicians to maintain a high level of vigilance and expertise in managing pediatric genitourinary injuries. Each condition presents unique challenges that require prompt recognition and specialized intervention to prevent serious complications and ensure optimal outcomes. The importance of multidisciplinary collaboration, including referrals to specialized centers and consultations with pediatric specialists, is paramount in addressing the physical and psychological impacts of these injuries.

Furthermore, the sensitive nature of some conditions, such as FGM/C, necessitates culturally informed approaches and careful communication with patients and families. By integrating comprehensive care strategies and fostering awareness, healthcare providers can play a pivotal role in safeguarding the health and well-being of children affected by genitourinary injuries, ultimately contributing to improved recovery and quality of life.

Chisom Agbim, MD, MSHS, is Clinical Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA.

Cherrelle Smith, MD, MS, is Clinical Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA.

Mia Karamatsu, MD, is Clinical Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA.

References

- Casey JT, Bjurlin MA, Cheng EY. Pediatric genital injury: An analysis of the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System. Urology. 2013;82(5):1125-1130.

- Dowlut-McElroy T, Higgins J, Williams KB, Strickland JL. Patterns of treatment of accidental genital trauma in girls. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2018;31(1):19-22.

- Spitzer RF, Kives S, Caccia N, et al. Retrospective review of unintentional female genital trauma at a pediatric referral center. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(12):831-835.

- McLaughlin CJ, Martin KL. Mechanism of injury and age predict operative intervention in pediatric perineal injury. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2023;39(4):230-235.

- Li KD, Al Azzawi S, Hakam N, et al. Consumer product-related female genital injuries in the USA from 2013 to 2022. Inj Prev. 2024 Oct 2:ip-2023-045166. doi: 10.1136/ip-2023-045166.

- Guerre D, Bréhin C, Gurrera E, et al. [Management of unintentional pediatric female genital trauma]. Arch Pediatr. 2017;24(11):1083-1087.

- Nabavizadeh B, Namiri N, Hakam N, et al. MP04-07 The epidemiology of playground equipment-related genital injuries in children: An analysis of United States emergency departments visits, 2010-2019. J Urol. 2021;206(Suppl 3):e69-e70.

- Takei H, Nomura O, Hagiwara Y, Inoue N. The management of pediatric genital injuries at a pediatric emergency department in Japan. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(2):73-76.

- Iqbal CW, Jrebi NY, Zielinski MD, et al. Patterns of accidental genital trauma in young girls and indications for operative management. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(5):930-933.

- Lopez HN, Focseneanu MA, Merritt DF. Genital injuries acute evaluation and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;48:28-39.

- Holland AJ, Soundappan SSv. Trauma hazards in children: An update for the busy clinician. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53(11):1096-1100.

- O’Brien K, Fei F, Quint E, Dendrinos M. Non-obstetric traumatic vulvar hematomas in premenarchal and postmenarchal girls. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2022;35(5):546-551.

- Propst AM, Thorp Jr JM. Traumatic vulvar hematomas: Conservative versus surgical management. South Med J. 1998;91(2):144-146.

- Lynch JM, Gardner MJ, Albanese CT. Blunt urogenital trauma in prepubescent female patients: More than meets the eye! Pediatr Emerg Care. 1995;11(6):372-375.

- Okur H, Küçükaydin M, Kazez A, et al. Genitourinary tract injuries in girls. Br J Urol. 1996;78(3):446-449.

- Guichard G, El Ammari J, Del Coro C, et al. Accuracy of ultrasonography in diagnosis of testicular rupture after blunt scrotal trauma. Urology. 2008;71(1):52-56.

- Fenton LZ, Karakas SP, Baskin L, Campbell JB. Sonography of pediatric blunt scrotal trauma: What the pediatric urologist wants to know. Pediatr Radiol. 2016;46(7):1049-1058.

- Scheidler MG, Shultz BL, Schall L, Ford HR. Mechanisms of blunt perineal injury in female pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35(9):1317-1319.

- Glaser ZA, Singh N, Koch C, Dangle PP. Pediatric female genital trauma managed under conscious sedation in the emergency department versus general anesthesia in the operating room — a single center comparison of outcomes and cost. J Pediatr Urol. 2021;17(2):236.e1-236.e8.

- McLaughlin CJ, Martin KL. Radiologic imaging does not add value for female pediatric patients with isolated blunt straddle mechanisms. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2022;35(5):541-545.

- Mok-Lin EY, Laufer MR. Management of vulvar hematomas: Use of a word catheter. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(5):e156-e158.

- Bergus K, Frooman A, Castellanos S, et al. Characterization of pediatric female genital trauma using a novel grading system and recommendations for management. J Pediatr Surg. 2024;59(10):161599.

- Merritt DF. Genital trauma in children and adolescents. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51(2):237-248.

- Habek D, Kulas T. Nonobstetrics vulvovaginal injuries: Mechanism and outcome. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;275(2):93-97.

- Hemal AK, Dorairajan LN, Gupta NP. Posttraumatic complete and partial loss of urethra with pelvic fracture in girls: An appraisal of management. J Urol. 2000;163(1):282-287.

- Podestá ML, Jordan GH. Pelvic fracture urethral injuries in girls. J Urol. 2001;165(5):1660-1665.

- Virgili A, Bianchi A, Mollica G, Corazza M. Serious hematoma of the vulva from a bicycle accident. A case report. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):662-664.

- Widni EE, Höllwarth ME, Saxena AK. Analysis of nonsexual injuries of the male genitals in children and adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(4):590-593.

- Jain R, Nadella M, Byrne R, et al. Epidemiology of testicular trauma in sports: Analysis of the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database. J Emerg Med. 2024;67(6):e544-e552.

- Papathanassiou ZG, Michalopoulou K, Alexopoulos V, Panagidis A. Testicular rupture: Clinical, sonographic, and surgical correlation in an adolescent patient. Cureus. 2025;17(2):e78688.

- Morey AF, Broghammer JA, Hollowell CMP, et al. Urotrauma guideline 2020: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 2021;205(1):30-35.

- Deurdulian C, Mittelstaedt CA, Chong WK, Fielding JR. U.S. of acute scrotal trauma: Optimal technique, imaging findings, and management. RadioGraphics. 2007;27(2):357-369.

- Munter DW, Faleski EJ. Blunt scrotal trauma: Emergency department evaluation and management. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7(2):227-234.

- Mellick LB, Sinex JE, Gibson RW, Mears K. A systematic review of testicle survival time after a torsion event. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(12):821-825.

- Torrey SB. Scrotal trauma in children and adolescents. UpToDate. Updated March 25, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/scrotal-trauma-in-children-and-adolescents

- Bieniek JM, Sumfest JM. Sports-related testicular injuries and the use of protective equipment among young male athletes. Urology. 2014;84(6):1485-1489.

- Barton DJ, Sloan GM, Nichter LS, Reinisch JF. Hair-thread tourniquet syndrome. Pediatrics. 1988;82(6):925-928.

- De Vitis LA, Barba M, Lazzarin S, et al. Female genital hair-thread tourniquet syndrome: A case report and literature systematic review. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34(1):65-70.

- Adjei NN, Lynn AY, Grimshaw A, et al. Systematic literature review of pediatric male and female genital hair thread tourniquet syndrome. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022;38(2):e799-e804.

- Djokic D, Milani GP, Lava SAG, et al. Hair-thread strangulation syndrome in childhood: A systematic review. Swiss Med Wkly. 2023;153:40124.

- Bean JF, Hebal F, Hunter CJ. A single center retrospective review of hair tourniquet syndrome and a proposed treatment algorithm. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(9):1583-1585.

- Diaz-Morales O, Martinez-Pajares JD, Ramos-Diaz JC, et al. Genital hair-thread tourniquet syndrome. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020;33(6):715-719.

- Umans E, Boogaerts M, Vergauwe B, et al. Vaginal foreign body in the pediatric patient: A systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2024;297:153-158.

- Stricker T, Navratil F, Sennhauser FH. Vaginal foreign bodies. J Paediatr Child Health. 2004;40(4):205-207.

- Ma W, Sun Y-F, Liu J-H, et al. Vaginal foreign bodies in children: A single-center retrospective 10-year analysis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2022;38(4):637-641.

- Lehembre-Shiah E, Gomez-Lobo V. Vaginal foreign bodies in the pediatric and adolescent age group: A review of current literature and discussion of best practices in diagnosis and management. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2024;37(2):121-125.

- Smith YR, Berman DR, Quint EH. Premenarchal vaginal discharge: Findings of procedures to rule out foreign bodies. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2002;15(4):227-230.

- Bagga HS, Tasian GE, McGeady J, et al. Zip-related genital injury. BJU Int. 2013;112(2):E191-E194.

- Chung P, Gomella L. How to remove a zipper from a penis — genitourinary disorders. In: Merck Manual Professional Edition. Revised May 2025. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/genitourinary-disorders/how-to-do-genitourinary-procedures/how-to-remove-a-zipper-from-a-penis

- Piszker A, Goodrich J, Koehler T, Offman R. Improvising on the fly: Comparison of a novel technique for emergent zipper release to a well-established technique in a simulated setting. J Emerg Med. 2024;67(4):e351-e356.

- Mishra SC. Safe and painless manipulation of penile zipper entrapment. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43(3):252-254.

- Raveenthiran V. Releasing of zipper-entrapped foreskin: A novel nonsurgical technique. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23(7):463-464.

- Mydlo JH. Treatment of a delayed zipper injury. Urol Int. 2000;64(1):45-46.

- Tresh A, Baradaran N, Gaither TW, et al. Genital burns in the United States: Disproportionate prevalence in the pediatric population. Burns. 2018;44(5):1366-1371.

- Angel C, Shu T, French D, et al. Genital and perineal burns in children: 10 years of experience at a major burn center. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37(1):99-103.

- Klaassen Z, Go PH, Mansour EH, et al. Pediatric genital burns: A 15-year retrospective analysis of outcomes at a level 1 burn center. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(8):1532-1538.

- Peck MD, Priolo-Kapel D. Child abuse by burning: A review of the literature and an algorithm for medical investigations. J Trauma. 2002;53(5):1013-1022.

- Cocanour C, Burd R, Davis J. ACS Trauma Quality Programs: Best practices guidelines for trauma center recognition of child abuse, elder abuse, and intimate partner violence. American College of Surgeons. Published 2019. https://doh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/Documents/2900//RecogChild-Elder-IntimateAbuse-PartnerViolence.pdf

- Bettencourt AP, Romanowski KS, Joe V, et al. Updating the burn center referral criteria: Results from the 2018 eDelphi Consensus Study. J Burn Care Res. 2020;41(5):1052-1062.

- Hewett Brumberg EK, Douma MJ, Alibertis K, et al. 2024 American Heart Association and American Red Cross guidelines for first aid. Circulation. 2024;150(24):e519-e579.

- Abel NJ, Klaassen Z, Mansour EH, et al. Clinical outcome analysis of male and female genital burn injuries: A 15-year experience at a level-1 burn center. Int J Urol. 2012;19(4):351-358.

- Hassfurter K. Female genital mutilation: A global concern. UNICEF Data. Updated March 7, 2024. https://data.unicef.org/resources/female-genital-mutilation-a-global-concern-2024/

- Young J, Nour NM, Macauley RC, et al; Section on Global Health; Committee on Medical Liability and Risk Management; Committee on Bioethics. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of female genital mutilation or cutting in girls. Pediatrics. 2020;146(2):e20201012.

- World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation. Published Jan. 31, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation

- LeMay C. Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) — a visual reference and learning tool for health care professionals. The U.S. End FGM/C Network. Published March 18, 2024. https://endfgmnetwork.org/female-genital-mutilation-cutting-fgm-c-a-visual-reference-and-learning-tool-for-health-care-professionals/