Lymphedema Risk After Pelvic Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Endometrial Cancer

July 1, 2025

By Alexandra Morell, MD

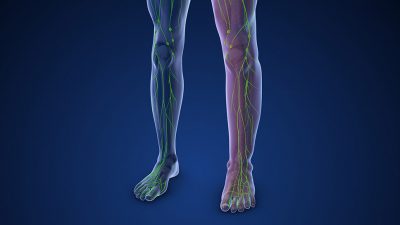

Synopsis: This prospective longitudinal cohort study in Denmark of women with low-grade endometrial cancer undergoing sentinel lymph node mapping during surgical staging demonstrated a statistically significant mean change in patient-reported outcome lymphedema scores from prior to surgery (5.0; 95% confidence interval, 3.3 to 6.8). However, the change did not meet preset thresholds for clinical importance (8.0 points). The study did identify body mass index (P = 0.01) and preoperative leg swelling (P < 0.01) as risk factors for lymphedema and demonstrated that this complication negatively affects several quality-of-life domains.

Source: Bjørnholt SM, Groenvold M, Petersen MA, et al. Patient-reported lymphedema after sentinel lymph node mapping in women with low-grade endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2025;232(3):306.e1-306.e11.

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in developed countries. In the United States, incidence and mortality rates currently are rising.1,2 Risk factors for developing endometrial cancer include unopposed estrogen exposure through medication use, chronic anovulation, obesity secondary to adipose cell-derived hormone production, age, nulliparity, early age of menarche, and late age of menopause.3 Certain genetic conditions, such as Lynch syndrome or Cowden syndrome, also predispose to development of endometrial cancer.

Most patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer initially present with abnormal uterine bleeding or postmenopausal bleeding.3-5 However, those with later stage at diagnosis also may describe abdominal bloating and pain, early satiety, or changes in bowel habits. Initial diagnosis usually is via endometrial sampling either by endometrial biopsy or hysteroscopy with dilation and curettage. Surgical staging of endometrial cancer involves total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, removal of any other obvious disease, evaluation of lymph nodes, and, sometimes, omental or peritoneal biopsies, depending on histology.4,5

Historically, lymph node evaluation was performed via complete pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. However, more recent guidelines support the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy as an acceptable alternative to complete nodal dissection. Sentinel lymph node mapping is a process in which tracer dye or radiocolloid (typically indocyanine green) is injected into the cervix and surgeons selectively remove lymph nodes where metastatic spread is most likely. If the sentinel lymph node mapping is not successful, then a standard lymphadenectomy is recommended.

This prospective longitudinal cohort study by Bjørnholt et al aimed to evaluate the risk of patient-reported lymphedema for women who underwent sentinel lymph node mapping during endometrial cancer staging and identify risk factors for lymphedema. This study enrolled 617 women with presumed stage I low-grade (grade 1 or 2) endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium from March 2017 to March 2022 from four medical centers in Denmark. During surgical staging procedures, these women underwent a sentinel lymph node mapping procedure with removal of any suspicious lymph nodes, ultra-staging at the time of pathology evaluation, and ipsilateral or bilateral lymphadenectomy if sentinel lymph nodes were not identified via mapping and greater than 50% myometrial invasion was present on frozen section evaluation.

Patients completed several validated questionnaires before surgery and then at two timepoints after surgery (at three and 12 months). The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Endometrial Cancer Module (EORTC-QLQ-EN24) leg lymphedema domain score was the primary outcome. Additional assessments regarding lymphedema were performed using seven single items from the EORTC item library and the Lymphedema Quality of Life Tool (LYMQOL). Using a 100-point scale, an eight-point score difference was deemed clinically important.

For statistical analyses, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and chi-square tests were used to evaluate demographic and patient characteristic differences. For lymphedema assessments, mean difference scores over time were calculated along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Multiple linear regression models were used to evaluate factors predictive of lymphedema at one-year post-surgery and to determine if early reporting of lymphedema (at three months) was predictive of later reporting of lymphedema (at 12 months). Statistical significance was defined as a P value < 0.05.

A total of 486 women were included in the primary analysis, after excluding women who were diagnosed with a recurrence within 12 months or who did not successfully complete the validated questionnaires. The only significant difference in demographic or clinical characteristics between participants who completed all questionnaires and those with incomplete responses was smoking status.

The baseline lymphedema score for all participants was 11.6. A baseline score takes into account generalized lower extremity swelling from alternative causes (such as venous stasis) in addition to baseline lymphedema from other causes (such as infection, genetic defects, or cancer-associated) but not secondary to surgery. Three months post-surgery the mean score was 16.0 and 12 months post-surgery the mean score was 16.5, which represented a statistically significant mean score change from baseline of 5.0 (95% CI, 3.3 to 6.8). However, this did not reach the preset limit of suspected clinical relevance of an 8.0-point difference.

Factors positively predictive of higher leg lymphedema score were body mass index (BMI) (R = 0.34; 95% CI, 0.08 to 0.61; P = 0.01) and baseline leg lymphedema (R = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.50 to 0.74; P < 0.01). The early lymphedema score at three months was correlated with later post-surgery lymphedema at 12 months (R = 0.52; 95% CI, 0.39 to 0.65). Lastly, regarding quality of life related to lymphedema, there was a statistically significant negative association in four domains, including daily activity functioning (R = -0.49; 95% CI, -0.60 to -0.39), appearance (R = -0.46; 95% CI, -0.57 to -0.35), emotional symptoms (R = -0.21; 95% CI, -0.30 to -0.11), and overall quality of life (95% CI, -0.45; 95% CI, -0.59 to -0.31). There also was an increase in subjective symptom burden (R = 0.58; 95% CI, 0.47 to 0.68).

Commentary

This prospective, longitudinal cohort study including women with early-stage low-grade endometrial cancers demonstrated a significant difference in validated lymphedema scores for patients undergoing sentinel lymph node mapping; however, this difference did not reach the preset threshold for clinical significance. In addition, the authors demonstrated that preoperative BMI and leg swelling were predictors of postoperative lymphedema risk. Furthermore, the presence of lymphedema at three months post-surgery was associated with an increased likelihood of persistent leg edema at 12 months. Lastly, leg lymphedema after sentinel lymph node biopsy was found to adversely affect multiple dimensions of the patients’ quality of life.

Historically, lymph node evaluation at the time of surgical staging involved a complete pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection. Up to about 40% of women undergoing lymph node dissection developed lymphedema. In 2017, a multicenter, prospective cohort study (the FIRES trial) aimed to determine the sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) of sentinel lymph node dissection in patients with clinical stage I endometrial cancer.6 It determined that sentinel lymph node dissection identified 97% of lymph node metastases with a false-negative rate of 3% and an NPV of 99.6%.

In 2020, the Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy vs Lymphadenectomy for Intermediate and High-Grade Endometrial Cancer Staging (SENTOR) trial published results demonstrating that sentinel lymph node biopsy had a sensitivity of 96% with a false-negative rate of 4% and an NPV of 99% in patients with a higher risk of nodal metastases (i.e., high-grade endometrial cancers).7 Overall, the FIRES and SENTOR trials demonstrated sentinel lymph node biopsy as an accurate and feasible method for detecting nodal metastases in endometrial cancer, including high-grade disease. Performing a sentinel lymph node biopsy is thought to minimize the risk of lymphedema overall, but prior physician-reported lymphedema rates have ranged from 1% to 21%.8,9

One strength of this article is the use of patient-reported outcome measures as opposed to relying solely on clinician-reported measures to provide a more nuanced and patient-centered understanding of lymphedema. Notably, the study also considered preoperative patient-reported symptoms, enabling a more accurate assessment of symptomatology likely related to surgery.

Although the overall risk of lymphedema following a sentinel lymph node biopsy is low and this study did not observe a clinically important change in lymphedema scores before and after surgery, persistent symptoms of lymphedema can negatively affect quality of life, as supported by this study. Therefore, preoperative counseling for endometrial cancer patients should include a discussion about lymph node evaluation and the low risk of this complication, as well as potential implications if it does occur. Furthermore, the authors determined BMI and preoperative leg swelling to be predictors of postoperative lymphedema and can be used to identify which patients may be at higher risk.

Alexandra Morell, MD, is Adjunct Instructor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY.

References

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33.

2. Giaquinto AN, Broaddus RR, Jemal A, Siegel RL. The changing landscape of gynecologic cancer mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139(3):440-442.

3. Crosbie EJ, Kitson SJ, McAlpine JN, et al. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2022;399(10333):1412-1428.

4. Hamilton CA, Pothuri B, Arend RC, et al. Endometrial cancer: A Society of Gynecologic Oncology evidence-based review and recommendations. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;160(3):817-826.

5. SGO Clinical Practice Endometrial Cancer Working Group; Burke WM, Orr J, Leitao M, et al. Endometrial cancer: A review and current management strategies: Part I. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134(2):385-392.

6. Rossi EC, Kowalski LD, Scalici J, et al. A comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy to lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer staging (FIRES trial): A multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):384-392.

7. Cusimano MC, Vicus D, Pulman K, et al. Assessment of sentinel lymph node biopsy vs lymphadenectomy for intermediate- and high-grade endometrial cancer staging. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(2):157-164.

8. Geppert B, Lönnerfors C, Bollino M, Persson J. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in endometrial cancer — feasibility, safety and lymphatic complications. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148(3):491-498.

9. Goncalves BT, Dos Reis R, Ribeiro R, et al. Does sentinel node mapping impact morbidity and quality of life in endometrial cancer? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023;33(10):1548-1556.