Evaluation and Management of Diplopia in the Emergency Department

July 1, 2025

By Meagan Verbillion, DO, FAAEM, FACEP, and Michael Larkins, MD

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Diplopia, also known as double vision, is an uncommon chief complaint among patients presenting to the emergency department (ED), where delays or inappropriate workup can lead to permanent neurologic/vision deficits and potentially death. The initial assessment of diplopia should determine whether it is monocular (localizes to one eye) or binocular (true misalignment of the eyes).

- Monocular diplopia is linked to a primary defect of a specific eye and can stem from dry eyes, refractive error, astigmatism, or, in rare cases, mass effect from a tumor. In general, isolated monocular diplopia does not require emergent imaging or extensive workup in the ED, and patients can be given outpatient referral to ophthalmology.

- Binocular diplopia represents a breakdown in the fusional capacity of the binocular system and normal neuromuscular coordination. It requires a thorough assessment for potential cerebrovascular accident, tumor, giant cell arteritis, diabetic mononeuropathy, cranial nerve dysfunction, myasthenia gravis, and post-surgical/nerve block complications, among others.

- Unilateral, isolated binocular diplopia of less than three months duration that suggests impairment of cranial nerve IV (trochlear nerve; patients unable to turn the gaze of one eye downward) or VI (abducens nerve; patients unable to turn the gaze of one eye laterally) generally is appropriate for outpatient workup with a neurologist or ophthalmologist, barring any systemic signs or symptoms of infection. However, bilateral findings would require evaluation for increased intracranial pressure and/or central nervous system infection.

- Binocular diplopia in patients with unilateral “down and out” gaze with associated mydriasis and ptosis is concerning for cranial nerve (CN) III palsy. This can be secondary to a compressive aneurysm or tumor warranting advanced imaging with computed tomography/computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), while a pupil-sparing CN III palsy is more consistent with diabetic mononeuropathy.

- If examination is concerning for multiple cranial nerve palsies, then MRI as well as neurology and ophthalmology consultation is needed to evaluate for potential neuromuscular diseases.

- The complaint of double vision also may be secondary to other serious interruptions of vision, such as glaucoma, globe rupture, orbital floor fracture, retinal detachment, and retinal vein/artery occlusion, which are out of the scope of this article to review and should be evident based on other aspects of the chief complaint and history.

- Depending on the severity of neurologic deficits and determined etiology, patients may require transfer to a higher level of care for further workup and treatment with interdisciplinary assessment.

Introduction

Diplopia is an uncommon presenting complaint in the emergency department (ED) that can be associated with life- and vision-threatening diagnoses. Comprehensive management typically requires an interdisciplinary team, often including both ophthalmology and neurology. This article provides emergency physicians with an organized resource that they can quickly reference for guidance on the assessment, management, and disposition of diplopia patients. The evaluation of diplopia in the ED begins with ruling out immediate threats to life/vision, followed by determining whether the diplopia is monocular or binocular. Monocular diplopia generally can be referred for outpatient care, while binocular diplopia requires further evaluation for potential stroke and may necessitate imaging and urgent consultation with either ophthalmology or neurology specialists.

Diplopia, more commonly known as double vision, is an infrequent ED chief complaint, with the most recent estimates in the United States suggesting it comprises 0.04% of ED visits.1 While less emergent conditions such as dry eyes and sleep deprivation can cause diplopia, life-threatening etiologies such as an intracranial hemorrhage, cavernous sinus lesions, and rapidly progressive neurological disorders also may be at play. This makes rapid assessment, workup, and determination of appropriate patient disposition vital in those presenting with diplopia.

Epidemiology

Previous studies have reported an incidence of 0.1% for diplopia being the presenting complaint among patients in the ED in the United States, although accurate determination is limited, given that patients with true diplopia may present with other chief complaints, such as dizziness, difficulty walking, weakness, etc.2 The most recent study to date, by De Lott and colleagues in 2017, estimates the incidence as an order of magnitude lower at 0.04% based on cases collected from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey between 2003 and 2012.1 Worldwide, diplopia has been reported with an incidence of 3.6/10,000 patients in Italy.3 Other studies have been conducted in South Korea and India to investigate the incidence of monocular vs. binocular diplopia, with binocular diplopia generally being reported as more common, although the lack of standardized reporting and mix of multicenter and single-center analyses makes quantification difficult.4,5

Etiology

Diplopia can have various causes, ranging from benign to emergent. A comprehensive review of all these causes is beyond the scope of this article. However, this article will focus on the most common and potentially dangerous differentials, categorized by monocular and binocular diplopia.

Binocular diplopia results from eye misalignment, while monocular diplopia is caused by an optical phenomenon specific to the affected eye. Any process or lesion affecting the innervation of the extraocular muscles of the eye(s) or their corresponding nuclei and tracts can lead to diplopia. The same applies to disease processes that interfere with blood vessels supplying the eye and surrounding structures, as well as abnormalities or infections that affect the brain. Lastly, there may be psychogenic factors contributing to the presentation of diplopia, especially in cases of monocular diplopia.

Anatomy

The eye is a circular structure composed of three layers, from outermost to innermost the sclera, choroid, and retina.6 Light projects onto the retina and, in conjunction with the rods and cones contained within, the retina is responsible for transmitting interpreted visual input (light intensity, color, and position) via the optic nerve to the brain.

The anterior part of the eye, where light enters, includes the transparent outermost layer (the cornea) with an anterior chamber filled with clear, thin fluid known as aqueous humor. The pupil is located behind the cornea and anterior chamber, formed by the donut-shaped iris, which contracts and relaxes to control the entry of light into the lens. This circular structure focuses light that passes through the pupil onto the retina at the back of the eye. Any defect or damage to these eye structures, such as lens opacification seen with cataracts or folding or tearing of the retina observed in retinal detachment, can result in monocular diplopia.

Six muscles of the eye control movement: the lateral and medial recti, the superior and inferior recti, and the superior and inferior obliques. The lateral and medial recti move each corresponding eye medially or laterally according to the cardinal planes, while the superior rectus shifts the eye superolaterally and the inferior rectus shifts the eye inferolaterally, based on the muscle’s positioning on the eye. The superior and inferior obliques, in turn, move the eye inferomedially and superolaterally, respectively.

These six muscles are controlled by corresponding cranial nerves (CNs): CN III (oculomotor) controls the medial, inferior, and superior recti as well as the inferior oblique, while CN IV (trochlear) controls the superior oblique, and CN VI (abducens) controls the lateral rectus.7 Damage or compression of any of these CN or corresponding eye muscles can lead to eye tracking failure and resultant diplopia. CN III also contains autonomic parasympathetic fibers responsible for pupillary constriction (miosis) and innervates the levator orbicularis superioris, which is responsible for elevation of the superior eyelid.8 Table 1 lists the six extraocular muscles, their corresponding cranial nerves, normal actions, and corresponding deficits if affected by disease pathology. Figure 1 shows the muscles of the eye and corresponding cranial nerves.

Table 1. Cranial Nerves of the Eye, Corresponding Extraocular Muscles, and Related Functions |

Cranial Nerve II (Optic)

Cranial Nerve III (Oculomotor)

Cranial Nerve IV (Trochlear)

Cranial Nerve VI (Abducens)

|

Figure 1. Extraocular Muscles and Corresponding Cranial Nerves |

|

Source: Romano N, Federici M, Castaldi A. Imaging of cranial nerves: A pictorial overivew. Insights Imaging 2019;10:33. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ [Modifications: text retyped for readability.] |

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for diplopia is extensive, and the clinical approach for the ED should be to prioritize those diagnoses associated with the greatest morbidity and mortality. In general, a thorough history and physical exam, including ultrasound, tonometry, slit lamp examination, and fundoscopy, can elicit the underlying pathology.9,10

All patients presenting with diplopia, whether monocular or binocular, should be evaluated for classic vision-threatening diagnoses in the ED, such as foreign body, lens dislocations/subluxations, retinal hemorrhage/detachment, retrobulbar hematoma, corneal abrasion, globe disruption, central retinal artery occlusion, central retinal vein occlusion, and glaucoma. Often these conditions will present with additional signs/symptoms and not simply isolated diplopia and are beyond of the scope of this article to cover.

Monocular diplopia is caused by intraocular pathology. The differential includes dry eyes, refractive error such as astigmatism or myopia, strabismus, retinal wrinkles, or corneal irregularities.9,11 Binocular diplopia is not only the more common presenting diplopia, but it also is associated with more potentially emergent diagnoses.9 The differential includes stroke, neuromuscular disease, cranial nerve palsies, tumor, autoimmune disease, infection/abscess, trauma, and diabetes, to name a few. See Table 2 for a more comprehensive list.

Table 2. Differential Diagnosis for Diplopia |

Monocular Diplopia

Binocular Diplopia

|

Monocular Diplopia

Dry Eyes

Patients presenting with a monocular diplopia with an associated feeling of dryness, stinging, burning, and/or difficulty generating tears should be considered for potential dry eyes syndrome.12 Patients may complain of grittiness, excessive blinking, and tired-feeling eyes as well. Generally, history and physical examination are sufficient to diagnose dry eyes. Consideration for medication-associated dry eyes is important, since many common medications such as antihistamines, anxiolytics, diuretics, anticholinergic medications, and antidepressants can induce dry eyes.

Strabismus

Patients presenting with obvious eye misalignment, in which one or both eyes deviate inward or outward during a focused gaze, should be considered to have strabismus.13 Commonly seen in children younger than 6 years of age with peak incidence around 3 years of age, this condition can be caused by refractive error, binocular fusion abnormalities, and neuromuscular problems.

Refractive Error

Patients with inadequately corrected refractive error, such as myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness), and presbyopia, may present with monocular diplopia, with concomitant blurred vision and squinting. This can be assessed during visual acuity examination, and it may help to assess if the patient has been evaluated for corrective lenses or if they regularly use them.

Retinal/Corneal Irregularities

Patients with obvious deformity of the cornea or retina (on fundoscopic examination or point-of-care ultrasound), history of optical surgery/trauma, and/or visual distortion in addition to monocular diplopia may have scarring of the cornea or retina, keratoconus, macular degeneration, or retinal detachment/wrinkling. Characteristically, patients with retinal detachment will have painless vision loss in one eye, sometimes likened to a curtain being pulled down in their vision, while those with macular degeneration will have vision loss confined to the central portion of their visual fields.14,15

Malingering/Conversion Disorder

Considered diagnoses of exclusion, malingering and conversion disorder (also known as functional neurologic disorder) are the product of behavioral and not organic/structural disease.16,17 Patients presenting with a normal physical exam and unremarkable testing may fall into this category. Malingering occurs when a patient reports a complaint with secondary gain, such as obtaining disability benefits, while in conversion disorder patients have no obvious gain and have an unremarkable workup.

Binocular Diplopia

Stroke

Patients presenting with binocular diplopia with associated neurologic deficits, such as facial droop, altered mental status, and ataxia, may have a stroke, an interruption to the blood flow to the brain. The initial history and physical for these patients should attempt to elicit the onset of symptoms as well as the full list of presenting neurologic deficits, since this will allow for determining the likely region affected by the stroke. In a study of 260 ED patients with non-traumatic binocular diplopia, a cause was identified in 93 (36%) and stroke accounted for almost half of the identifiable causes.2

Cranial Nerve Palsies

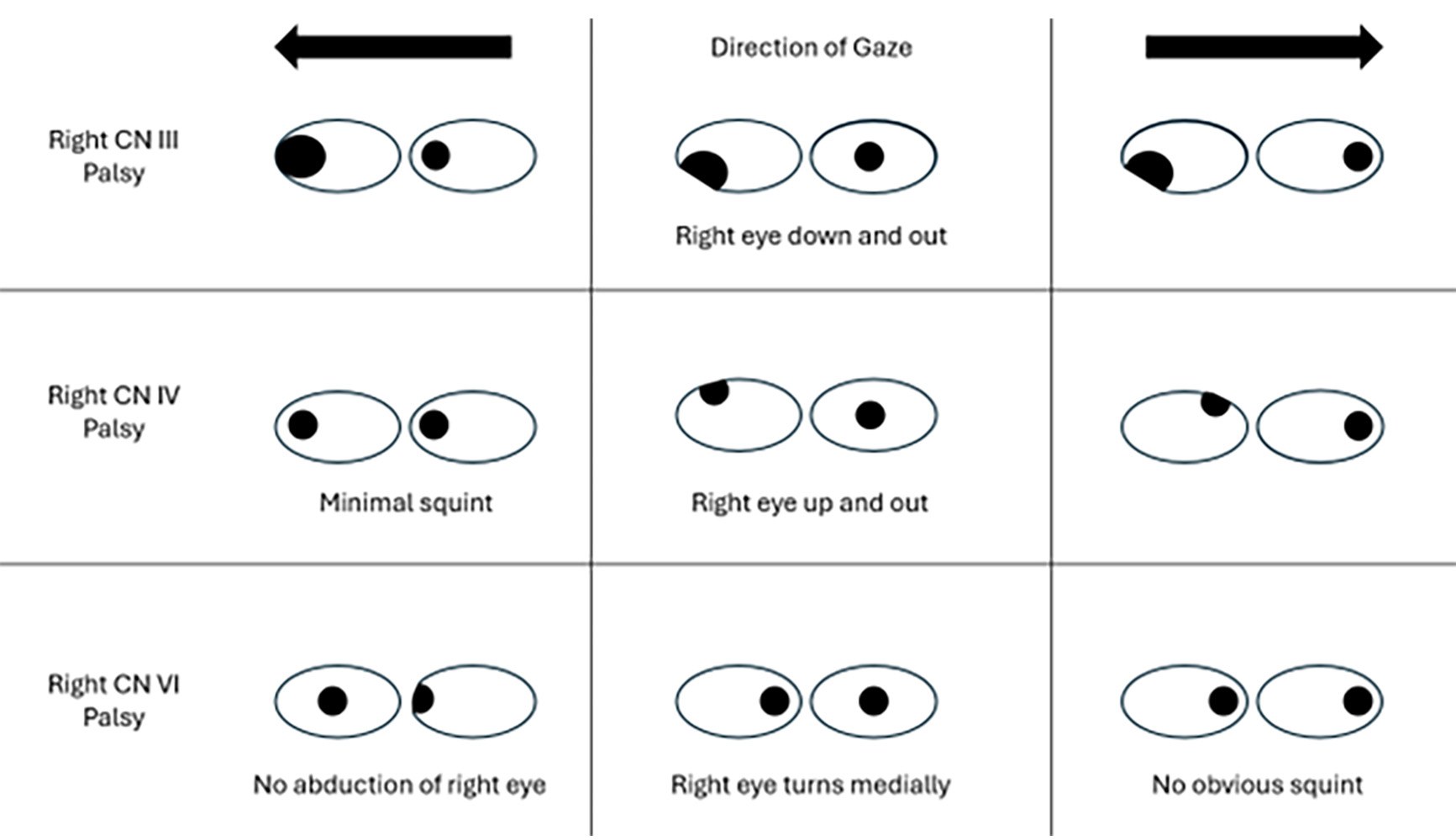

Patients with diplopia in specific directions of gaze without any other associated symptoms or deficits may have an isolated cranial nerve (CN) palsy. Patients with associated ptosis and pupil dilation may have a palsy of CN III, while those with vertical or torsional diplopia, which is worse when looking down and/or recent trauma, may have a palsy of CN IV.9 Those with diplopia that worsens with lateral gaze in one direction, on the other hand, more likely have a palsy of CN VI. Given the length of CN VI, it is the most common CN palsy.

Tumor/Compressive Lesion

In contrast to patients with isolated CN palsies, those with multiple CN palsies with associated orbital discomfort or headache may have a compressive lesion within the head causing pathology.9 Two areas of congestion associated with such lesions are the orbital apex, which is the posterior portion of the orbit and contains CN II, III, IV, V, and VI; and the cavernous sinus, which sits in the skull base and contains CN III, IV, V, VI, and the internal carotid artery. Lesions can be localized by the presence of decreased visual acuity given the orbital apex contains the optic nerve. Patients with multiple CN deficits and decreased visual acuity are more likely to have pathology here.

Neuromuscular Disorders

Patients with isolated binocular diplopia and a physical exam concerning for multiple involved CN should be assessed for potential autoimmune diseases, such as myasthenia gravis or multiple sclerosis.9 Mild forms of myasthenia gravis may present with unidirectional diplopia, and additionally it is important to note that 50% of patients with myasthenia gravis may present with solely ocular symptoms, without other associated neurologic deficits such as shortness of breath or difficulty swallowing. Patients also will have fatigability with repetitive motions and diplopia that fluctuates over time. Applying an ice pack to the patient’s closed eye for five minutes with improvement in ptosis is suggestive of myasthenia gravis.

With multiple sclerosis, a common form of diplopia is internuclear ophthalmoplegia. This form of diplopia is visible on horizontal gaze, where the affected eye can only weakly adduct (look outward) and the contralateral eye will display abduction nystagmus, nystagmus on inner gaze. This condition is caused by a lesion in the medial longitudinal fasciculus that connects the CN VI nucleus with the medial rectus nucleus in the CN III. This connection coordinates lateral conjugate gaze movement. In patients younger than 45 years of age, the most common cause of internuclear ophthalmoplegia is multiple sclerosis, and it is bilateral in about three-fourths of these patients.

Endocrinopathies

The most relevant endocrinopathy for patients presenting with binocular diplopia is thyroid eye disease, usually in the setting of Graves’ disease, although other thyroid conditions can be implicated.9 Patients may present with solely unilateral diplopia, although additional concerning features include eyelid retraction, proptosis, and vascular injection.

Intracranial Abscess

Like tumors/compressive lesions, intracranial abscess can constitute a structural orbitopathy that can restrict eye movement.9 Generally this will have a gradual onset, and associated symptoms include head/ocular pressure/pain, fever, and altered mental status. The infectious component of this pathology may lead to fevers and chills, as well as systemic evidence of infection, such as an elevated white blood cell count or elevated inflammatory markers.

Diabetes

Diabetes, particularly among patients with poorly controlled disease, has been implicated in cranial neuropathies likely secondary to microvascular occlusion.18 Most commonly CN III is affected. This makes a thorough history and blood glucose level important tools in the assessment of patients with binocular diplopia.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy, for instance with pembrolizumab in the setting of cancer, has been implicated in the development of bilateral horizontal diplopia thought to be secondary to systemic inflammation.19 Careful review of the patient history and systems as well as identification of any such agents is important in the assessment of patients with diplopia. Treatment with steroids and immunoglobulin may be beneficial in such patients.

Preeclampsia/Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

Patients presenting with diplopia when pregnant or within a few months of delivery should be assessed for potential preeclampsia and eclampsia.20 Obstetric history should be obtained, and blood pressure should be assessed and ultimately controlled. Patients have been reported in the postpartum period with hypertension and CN VI palsy, which resolved with administration of antihypertensives. Similarly, idiopathic intracranial hypertension has been reported in a pediatric patient presenting with acute onset diplopia and lateral rectus paralysis.21

Opioids

Although the mechanism currently is not known, there has been at least one case of diplopia reported after treatment with hydromorphone.22 It is possible opioid-naïve patients may develop blurred vision in the setting of the sedative effects of opioids, and asking patients about recent opioid use should be a part of patient interviews.

Neuraxial Blocks and Surgery

Cranial nerve palsies are a rare complication of neuraxial blocks, but they are more common among obstetric and gynecologic patients.23 This stems from nerve compression or traction from intracranial hypotension, with the most frequently affected being CN VI. Following spinal and epidural anesthesia, CN VI and III are affected most commonly because of fluctuations in cerebrospinal fluid pressure. Surgical procedures involving ophthalmology, otolaryngology, or neurosurgery are most likely to lead to CN palsies given their overall anatomical proximity to the cranial nerves.

Orbital Floor Fractures

Patients presenting with binocular diplopia in the setting of head trauma should be assessed for potential orbital fractures.24 These fractures are common since orbital bones are thin and fragile. Patients with diplopia, especially on upward gaze, as well as those with limitation in upward gaze, poor visual acuity, and tenderness or step-offs around the orbital rim, should be assessed further for potential orbital fracture with advanced imaging such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Primary Idiopathic Diplopia

It is possible that despite a comprehensive evaluation, a specific cause for binocular diplopia is not found. Such cases are termed primary or idiopathic diplopia. In a study of 260 ED patients with non-traumatic binocular diplopia, 167 (64%) were identified as primary diplopia.2 It generally is assumed that most of these cases are due to microvascular ischemic disease.

Clinical Features

Diplopia or double vision is described as seeing two or more images. The approach to assessing diplopia in the ED was laid out by Margolin and Lam in 2018, which emphasized first determining whether the patient’s diplopia is binocular or monocular.25 This can be assessed while obtaining the history by asking the patient, “Does the double vision resolve when you close one eye, and if so, which eye?” If the double vision resolves when closing an eye, this is representative of binocular diplopia. This should be corroborated during the physical exam by having the patient close/cover each eye individually and then assessing the change in vision. It is critical that immediate threats to vision, including but not limited to globe fractures, retinal hemorrhage, and glaucoma, are considered during this initial stage in evaluation.

Additional information that should be gathered includes the timing, onset, and associated symptoms, directionality of the diplopia, and presence or absence of pain.9 Sudden onset is more indicative of ischemic or vascular disease, while fluctuation over time can be indicative of transient ischemic attacks, impending stroke, or neuromuscular disease. Atraumatic ocular pain, especially with movement, is suggestive of an inflammatory or infectious process within the orbit. Horizontal diplopia (images are side-by-side) is more indicative of medial or lateral rectus pathology, while torsional diplopia is more indicative of superior or inferior oblique pathology. Vertical diplopia is more commonly associated with involvement of the brain or brainstem, although it can indicate CN IV palsy.

Two additional questions can be helpful in localizing the impairment with binocular diplopia. Ask if there is a direction of gaze that makes the diplopia worse. This direction indicates the visual field of a weakened muscle. Ask if there is a head position that improves diplopia. Tilting of the head can improve the oblique diplopia from a CN IV palsy. Neck flexion or extension can improve vertical diplopia.

Progressive symptoms should raise concern for a compressive lesion, while intermittent symptoms, especially if they are worse with movement, are concerning for myasthenia gravis and neuromuscular disease. Past medical history should focus on factors such as cardiac disease, tobacco use, hypertension, and diabetes. Family history should include questions about autoimmune disease, such as multiple sclerosis or lupus, neuromuscular disorders, and vascular disease. Table 3 includes a summary of the common diagnoses with associated clinical features and treatments of diplopia.

Table 3. Common Causes of Diplopia and Associated Features and Treatments | ||

Monocular | ||

Type | Diagnosis | Treatment |

Refractive error | Diplopia in one eye, persists with other eye closed; ghost images; improves with pinhole | Corrective lenses (glasses or contact lenses) |

Cataract | Cloudy lens, glare, halos; monocular diplopia, especially at night | Cataract surgery |

Corneal irregularities | Keratoconus, scars, or dystrophies; distortion of image | Rigid contact lenses, corneal transplant, cross-linking |

Lens displacement (ectopia lentis) | Marfan syndrome, trauma; monocular diplopia, asymmetric lens position | Corrective lenses or surgery (lens removal or repositioning) |

Dry eye/tear film issues | Fluctuating vision, worse after blinking or prolonged eye opening | Artificial tears, punctal plugs, lid hygiene |

Binocular | ||

Cranial nerve palsies | CN III: ptosis, eye down/out; CN IV: vertical diplopia; CN VI: horizontal diplopia | Treat underlying cause (e.g., DM, HTN, trauma); prism glasses; surgery |

Myasthenia gravis | Fatigable weakness, ptosis, variable diplopia | Anticholinesterase inhibitors, steroids, immunotherapy |

Thyroid eye disease | Restrictive ophthalmopathy, proptosis, diplopia on gaze extremes | Steroids, orbital decompression, strabismus surgery |

Orbital mass/trauma | Pain, proptosis, limited motility | Surgery, radiation, or steroids (based on cause) If abscess present: antibiotics and/or surgery |

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO) | Impaired adduction on affected side, nystagmus in contralateral abducting eye | Treat underlying cause (often MS or stroke); supportive care |

Brainstem stroke/lesion | Sudden onset diplopia, other neurologic deficits (e.g., ataxia, dysarthria, paralysis, sensory deficits) | Stroke management (e.g., thrombolysis, rehab) |

CN: cranial nerve; DM: diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; MS: multiple sclerosis | ||

Physical Exam

Thorough physical examination of patients with diplopia should include assessment of the cranial nerves as well as asymmetry.9 The presence of neurologic deficits on the contralateral body is concerning for brainstem involvement. Assessment of the eye bilaterally should include visual acuity, visual fields, pupillary exam, testing of extraocular movements, slit lamp examination, and fundoscopic examination. Ocular tonometry can be used if there is concern for increased intraocular pressure, while ultrasound can screen for papilledema and retinal detachment.

Examination of the external eye should include assessing the conjunctiva for injection, inflammation, chemosis, and hemorrhage. Evaluation for ptosis, lid lag, and proptosis also should be performed. Unilateral lack of tracking may be the result of entrapment from an orbital floor fracture. Proptosis can result from retrobulbar hematoma, compressive lesions, and thyroid eye disease in the setting of Graves’ disease.

Slit lamp examination allows for assessment of the external eye, including irregularities of the pupil, inflammatory changes in the anterior chamber, opacification of the lens, and lens subluxation. Fundoscopic examination allows for evaluation of the posterior eye to include the retina and optic nerve and should be used to assess for retinal involvement and papilledema.

Monocular Diplopia

If diplopia persists when the normal eye is covered/closed, this represents monocular diplopia, thus making a primary eye defect likely. Monocular diplopia should resolve with pinhole testing.9 Etiologies generally are benign, and further ED workup and imaging is not likely to be fruitful. Patients can be given an urgent outpatient ophthalmology referral. Symptomatic management, such as covering the eye with an eye patch, can be considered if close outpatient management is an option.

Binocular Diplopia

Diplopia that resolves with closure of either eye and is not lateralizing is suggestive of binocular diplopia and, thus, misalignment of the visual axes. Up to one-third of ED patients with binocular diplopia have a secondary cause, such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, and cerebral aneurysms.9 Binocular diplopia associated with other focal neurologic symptoms, such as vertigo, aphasia, ataxia, and concurrent contralateral hemiparesis or hemianesthesia, is concerning for central pathology and warrants a stroke workup.25

Patients with isolated impaired extraocular movement raise the concern for a palsy of cranial nerves III, IV, and/or VI. Patients presenting with mydriasis, ptosis, and a “down-and-out” eye with inability for the patient to turn the eye superiorly or medially is consistent with palsy of CN III, with the most concerning etiology being a compressive aneurysm at the junction of the posterior communicating and internal carotid arteries.26 Pupil-sparing CN III palsy is associated with diabetic mononeuropathy and/or hypertension related to microvascular disease and typically is self-resolving, requiring blood glucose and/or pressure control and close outpatient ophthalmology and primary care follow-up. Although, caution should be taken, since this is not a hard and fast rule, and, rarely, a compressive aneurysm can be pupil-sparing.9

CN IV palsy generally presents more subtly, with vertical or oblique diplopia, and most commonly is incited by trauma or progression of a congenital subclinical palsy.25 One particular traumatic example is an orbital floor blowout fracture, which can entrap the inferior rectus and lead to limited upward gaze with the affected eye. There are reports of this phenomenon presenting in a delayed fashion months after traumatic injury.10 Additionally, diplopia and entrapment can be complications of orbital floor fracture repair procedures.27 Patients with isolated CN IV palsies without inciting trauma are most likely to have congenital etiologies, and these patients, especially pediatric ones, can be mistaken for having torticollis since they often have a head tilt toward the affected side.28,29

Isolated (unilateral) CN VI palsy has been noted in the literature to often be caused by micro ischemia, is self-resolving, and can be followed up as an outpatient with ophthalmology.30 However, there are rare reports of isolated CN VI palsies associated with herpes zoster ophthalmicus and preeclampsia.31 Bilateral CN VI palsies connote more serious diagnoses stemming from increased intracranial pressure (ICP) or CNS infection. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension also is a consideration here.21 In the setting of CN lesions, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be obtained to rule out a compressive lesion if the diplopia has been ongoing for more than three months, although children should undergo imaging regardless of duration of symptoms since the likelihood of compression lesion is much greater.20 For all CN palsies, neuraxial blocks and diabetes have been implicated as well.18,23 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2. Physical Exam Findings of Patients with Isolated Palsies of Cranial Nerves III, IV, and VI |

Exam findings with testing of patient extraocular movements with associated unilateral cranial nerve palsies. For bilateral palsies, the abnormal portion of the exam seen in this figure would be duplicated bilaterally. |

|

Patients with binocular diplopia and multiple extraocular movement abnormalities concerning for more than one CN palsy need evaluation with MRI as well as consultation with neurology because of the possibility of cavernous sinus thrombosis/mass and neuromuscular disorders, such as myasthenia gravis and multiple sclerosis.25,32-34 Reports of associated seronegative ocular myasthenia gravis, for instance, have been made in patients presenting with transient dizziness and diplopia.35 Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome also has been implicated in multiple CN palsies secondary to thiamine deficiency, which explains the ophthalmoplegia component of the classic triad of this disease.36

Surgery and neuraxial blocks are iatrogenic causes of isolated CN palsies.23 Otolaryngologic (ENT) and neurosurgical procedures are the most common, given their potential proximity to the relevant CN.37-40 Additionally, neurotoxin injections such as botulinum and cosmetic procedures such as hyaluronic acid injections also have been implicated. Spinal and epidural anesthesia are the most prevalent neuraxial blocks to lead to CN dysfunction.

An additional consideration among patients presenting with diplopia is thyroid eye disease.41,42 This generally presents as a complication of Graves’ disease, in which patients present with irritability, muscle weakness, increased deep tendon reflexes, and the classic exophthalmos, in which the patient’s eyes bulge outward from the face. This is secondary to the buildup of immune-mediated cells and proteins behind the eye, and the mass effect from this buildup can cause the eyes to bulge asymmetrically, resulting in diplopia.

Giant cell arteritis, which may present with headache with temporal pain, jaw claudication, blurred vision, and vision loss, also can present with binocular diplopia.43 Recommended laboratory tests for evaluation include a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels on patients older than 50 years of age. Additionally, ultrasound can be used to evaluate for temporal artery inflammation, although biopsy and response to empiric treatment are more sensitive for diagnosis.44 Empiric treatment with high-dose steroids should be initiated once the diagnosis is considered likely, since confirmatory tissue diagnosis will be delayed and vision impairment/loss can be permanent. On a related note, systemic lupus erythematosus can lead to the development of cerebral vasculitis with resultant diplopia.45 Failure to recognize and address this manifestation of lupus can lead to long-term visual deficits.

Rarer causes of diplopia also have been reported in the literature, including immunotherapeutic agents such as pembrolizumab and other immunotherapies, insecticides, statins, COVID-19 and other viral infections, cancers including squamous cell carcinoma of the lung and blood, paraneoplastic syndrome associated with Hodgkin lymphoma, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, and opioids.18,19,21,23,46-52 Furthermore, patients with recent ophthalmology surgery may develop strabismus, leading to diplopia.53 Lyme disease also has been implicated in patients presenting with neck pain, binocular diplopia, and unilateral oculomotor nerve palsy.54

Management/Diagnostic Studies

Diplopia that Does Not Resolve When One Eye Is Covered: Monocular Diplopia

Patients presenting with diplopia determined to be monocular generally can be discharged with referral to an ophthalmologist. Other related illnesses with potential threat to life or vision also should be ruled out, including acute angle closure glaucoma, retinal detachment, retrobulbar hematoma, and globe rupture. Consider management with an eye patch or over-the-counter analgesics if particularly bothersome for the patient. See Table 3 for additional suggestions.

Diplopia that Resolves with Coverage of One Eye: Binocular Diplopia

Those found to have binocular diplopia with associated neurologic signs/symptoms should be assessed for potential stroke with CT and CT angiogram (CTA) as well as MRI. If these patients are within a thrombolytic window, consideration should be given to initiating thrombolysis. In addition to stroke, consider other diagnoses, such as giant cell arteritis, diabetes, and recent surgery/neuraxial blocks, as potential causes. Red flags here include pain with palpation of the temporal area and elevated inflammatory markers, and suspicion should be greater in older patients (> 50 years of age).

Binocular Diplopia Without Signs/Symptoms Suggestive of Central/Brainstem Pathology

If neurologic signs and symptoms such as ataxia, aphasia, hemiplegia, and hemianesthesia are not present, the patient has isolated diplopia. The next step in analysis is assessing the focality based on examination of the extraocular movements. Patients with inability to move either eye superiorly and medially, often with associated mydriasis and ptosis, likely have a palsy of CN III and should undergo CT and CTA imaging to assess for compressive pathology, such as a berry aneurysm with or without subarachnoid bleeding. The addition of CTA (or magnetic resonance angiogram, MRA) to CT imaging is important, since CT scanning alone without assessment of the vasculature may miss an underlying aneurysm.47 Another consideration here, especially if the patient is complaining of acute, painful associated anisocoria and/or anhidrosis, miosis, and ptosis, is Horner syndrome, potentially from a tumor or carotid artery dissection.

Those with inability to either abduct or perform a combination of eye depression, abduction, and intorsion likely have involvement of CN VI and IV, respectively. Bilateral involvement raises the concern for potentially increased ICP or infection of the central nervous system (CNS) such as meningitis, and should be worked up accordingly, with basic laboratory tests, inflammatory markers, and cultures obtained. On the other hand, patients with unilateral nerve palsies of CN VI and IV can undergo outpatient management with consultation to neurology or ophthalmology.

Figure 3. Updated Approach to Patients Presenting with Diplopia to the Emergency Department |

Algorithmic approach to those with diplopia. |

|

GCA: Giant cell arteritis; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; CN: cranial nerve; CT: computed tomography; CTA: computed tomography angiogram; ICP: intracranial pressure; CNS: central nervous system; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging Adapted from: Margolin E, Lam CTY. Approach to a patient with diplopia in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2018;54(6):799-806 |

Medicolegal Considerations

Patients presenting with neuro-ophthalmologic complaints carry a potential for misdiagnosis and, given the inherent risk to life/vision associated with these complaints, an increased risk of medicolegal risk.55,56 Among ophthalmologists, these conditions carry a risk of misdiagnosis as high as 60% to 70%, which likely translates to an even greater risk among emergency physicians. The most frequent cited reason for malpractice among retrospective reviews was failure to diagnose, with another study among ophthalmology trainees reporting this as the second most common reason for malpractice following errors in surgical technique.57,58 As seen across most specialties, a patient’s decision to pursue litigation has been linked more to feelings of being undervalued or misunderstood than to actual clinical errors, making the maintenance of the doctor-patient relationship crucial, especially among patients with high-risk neuro-ophthalmologic complaints such as diplopia.59

Disposition

As previously stated, patients found to have monocular diplopia can be discharged with outpatient referral to an ophthalmologist after other serious ophthalmologic illnesses have been ruled out. Those with binocular diplopia with findings consistent with a unilateral CN IV and/or CN VI palsy also can have outpatient ophthalmology or neurology follow-up. It should be noted that patients may have partial or incomplete deficits making the neuro-ophthalmologic examination complex. Consultation with the neurology specialist before discharge should be considered.

Those presenting with binocular diplopia and associated neurologic signs and symptoms should be admitted for an evaluation for stroke or other secondary causes. Similarly, those with findings consistent with a CN III deficit or multiple CN palsies should undergo further imaging and consultation with a neurologist and/or ophthalmologist. These patients may require transfer to a higher level of care for further workup, treatment, and access to consultants depending on the resources of the ED where the patient is initially assessed.

Summary

Diplopia is an uncommon presenting complaint for patients in the ED, but it can reflect severe life- and vision-threatening illness. The organized assessment of patients with true diplopia is important to identify such diseases, and this starts with the determination of monocular vs. binocular diplopia, with binocular diplopia requiring more caution and a workup to rule out stroke, giant cell arteritis, compressive CNS lesion, or neuromuscular disease. It is vital to consider other vision-threatening diagnoses, such as acute angle closure glaucoma, globe rupture, and central retinal artery and vein occlusions, in parallel with the diagnoses focused on the algorithm presented in this article. Diplopia frequently will require a multidisciplinary approach for patient treatment and disposition.

Meagan Verbillion, DO, FAAEM, FACEP, is Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine, Associate Program Director, Emergency Medicine Residency, Wright State University, Dayton, OH.

Michael Larkins, MD, is Emergency Medicine Resident, Boonshoft School of Medicine, Wright State University, Dayton, OH.

References

1. De Lott LB, Kerber KA, Lee PP, et al. Diplopia-related ambulatory and emergency department visits in the United States, 2003-2012. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(12):1339-1344.

2. Nazerian P, Vanni S, Tarocchi C, et al. Causes of diplopia in the emergency department: Diagnostic accuracy of clinical assessment and of head computed tomography. Eur J Emerg Med. 2014;21(2):118.

3. Raucci U, Parisi P, Vanacore N, et al. Acute diplopia in the pediatric emergency department. A cohort multicenter Italian study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017;21(5):722-729.

4. Kim J, Sun CL, Mailey B, et al. Race and ethnicity correlate with survival in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(1):152-160.

5. Kumar A, Sharma R, Verma AK, et al. An unusual case of adamantinoma of long bone. Autopsy Case Rep. 2024;11:e2021276.

6. Walker RA, Adhikari S. Chapter 241: Eye Emergencies. In: Tintanelli’s Emergency Medicine. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2020:1523.

7. Glisson CC. Approach to diplopia. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019;25(5):1362.

8. Joyce C, Le PH, Peterson DC. Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 3 (Oculomotor). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated March 27, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537126/

9. Norse AB. Chapter 17: Diplopia. In: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2023:158-166.

10. Tsuji S, Hosokawa Y, Sato H, et al. Sudden diplopia two months after a blowout fracture: A case report of orbital tissue adhesion associated with acute sinusitis. Cureus. 2025;17(1):e77659.

11. Tan A, Faridah H. The two-minute approach to monocular diplopia. Malays Fam Physician. 2010;5(3):115-118.

12. Golden MI, Meyer JJ, Zeppieri M, Patel BC. Dry Eye Syndrome. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated Feb. 29, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470411/

13. Kanukollu VM, Sood G. Strabismus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560782/

14. Blair K, Czyz CN. Retinal Detachment. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated Nov. 13, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551502/

15. Ruia S, Kaufman EJ. Macular Degeneration. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 31, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560778/

16. Peeling JL, Muzio MR. Functional Neurologic Disorder. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated May 8, 20223. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551567/

17. Alozai U, McPherson PK. Malingering. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 12, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507837/

18. Bell DSH. Diabetic mononeuropathies and diabetic amyotrophy. Diabetes Ther. 2022;13(10):1715-1722.

19. Garcez D, Clara AI, Moraes-Fontes MF, Marques JB. A challenging case of eyelid ptosis and diplopia induced by pembrolizumab. Cureus. 2022;14:e28330.

20. Yevale A, Vasudeva A, Mundkur A, et al. Isolated sixth cranial nerve palsy in a case of severe pre-eclampsia presenting as postpartum diplopia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(8):QD01-QD02.

21. Lohiya S, Tidake P, Walavalkar R. Acute onset diplopia and squint as the only presentation of idiopathic intracranial hypertension in a six-year-old. J Evoluation Med Dent Sci. 2021;10:323-325.

22. Lee LJ, Bungart B, Wainger B, et al. Transient acute diplopia as a rare side effect of hydromorphone: A case report. A A Pract. 2024;18:e01780.

23. Manici M, Görgülü RO, Darçın K, Gürkan Y. Cranial nerve palsies following neuraxial blocks. Agri. 2024;36(4):209-217.

24. Koenen L, Waseem M. Orbital Floor Fracture. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated Dec. 15, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534825/

25. Margolin E, Lam CTY. Approach to a patient with diplopia in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2018;54(6):799-806.

26. Sujijantarat N, Antonios JP, Renedo D, et al. Improvement in cranial nerve palsies following treatment of intracranial aneurysms with flow diverters: Institutional outcomes, systematic review and study-level meta-analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2024;246:108555.

27. De Ruiter BJ, Kotha VS, Peiffer AJ, et al. Orthoptic vision therapy: Establishing a protocol for management of diplopia following orbital fracture repair. J Craniofac Surg. 2021;32:1025-1028.

28. Choi H, Kim SY, Kim SJ, et al. Torsion and clinical features in patients with acquired fourth cranial nerve palsy. Sci Rep. 2024;14:7306.

29. Dosunmu EO, Hatt SR, Leske DA, et al. Incidence and etiology of presumed fourth cranial nerve palsy: A population-based study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;185:110-114.

30. Elder C, Hainline C, Galetta SL, et al. Isolated abducens nerve palsy: Update on evaluation and diagnosis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16(8):69.

31. Afshar F, Khalilian MS, Pourazizi M, Najafi MA. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus with acute retrobulbar optic neuritis and abducens nerve palsy: A case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025;25:23.

32. Akammar A, Sekkat G, Kolani S, et al. Unusual cause of binocular diplopia: Cavernous sinus hemangioma. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16:2605-2608.

33. Tutar NK, Omerhoca S, Kale N. The diagnostic challenge of ptosis and diplopia: Cavernous sinus syndrome as the sole sign of unknown pancreatic cancer. Indian J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2021;1:593-595.

34. Dogru-Huzmeli E, Duman T, Cakmak AI, Aksay U. Can diplopia complaint be reduced by telerehabilitation in multiple sclerosis patient during the pandemic?: A case report. Neurol Sci. 2021;42(10):4387-4390.

35. Yoshioka N, Naito Y, Sano K, et al. Seronegative ocular myasthenia gravis in an older woman with transient dizziness and diplopia. Cureus. 2022;14:e27826.

36. Isen DR, Kline LB. Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations of Wernicke encephalopathy. Eye Brain. 2020;12:49-60.

37. Urbina PP, García EH, de Liano Sánchez RG, Gordo BD. Restrictive strabismus and diplopia after conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy with Jones tube. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2021;44:e187-e190.

38. Garcia Sobral C, Silva e Sousa L, Chamusca R. P205 A rare complication of post-dural puncture — horizontal binocular diplopia post-dural puncture: A case report. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine. 2024;49:A229-A230.

39. Kim JY, Kim H, Kang SJ, et al. Diplopia developed by cervical traction after cervical spine surgery. Yeungnam Univ J Med. 2021;38:152-156.

40. Miyagi Y, Urasaki E. Diplopia associated with loop routing in deep brain stimulation: Illustrative case. J Neurosurg Case Lessons. 2021;1:1-4.

41. Issa M, Cioana M, Popovic MM, et al. Analysis of diplopia referrals in a tertiary neuro-ophthalmology center. Can J Ophthalmol. 2025; Apr 2. doi:10.1016/j.jcjo.2025.03.001. [Online ahead of print].

42. Mavridis T, Velonakis G, Zouvelou V. Painful diplopia: Do not forget thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Am J Med. 2021;134:e239-e240.

43. Hino C, Edigin E, Aihie O, et al. Analysis of emergency department visits by patients with giant cell arteritis: A national population-based study. Cureus. 2023;15(2):e35121.

44. Hernández P, Al Jalbout N, Matza M, et al. Temporal artery Uutrasound for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis in the emergency department. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e42350.

45. Ariana A. Diplopia as the initial manifestation of cerebral vasculitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: Diagnostic approach and challenges. Indian J Forensic Med & Toxicol. 2022;16:278.

46. Douglas RS, Dailey R, Subramanian PS, et al. Proptosis and diplopia response with teprotumumab and placebo vs the recommended treatment regimen with intravenous methylprednisolone in moderate to severe thyroid eye disease: A meta-analysis and matching-adjusted indirect comparison. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140:328-335.

47. Jiang H, Bu X, Liu T, Jiang B. Oculomotor nerve palsy caused by imidacloprid at initial diagnosis: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e39160.

48. Abdelmasih R, Abdelmaseih R, Reed J. A rare case of statin-induced diplopia: An often-overlooked but reported side effect. Cureus. 2021;13:e15117.

49. Sugg K, Diab W, Kappagantu A, Yazdanpanah O. Binocular diplopia: An unusual presentation of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Cureus. 2022;14:e27008.

50. Bin Waqar SH, Rehan A, Salahi N, et al. An exceptional case of diplopia and ptosis: Extramedullary plasmacytoma of the clivus with multiple myeloma. Cureus. 2022;14:e23219.

51. Fiorelli N, Fraticelli S, Bonometti A, et al. Hodgkin lymphoma with diplopia and nystagmus: A paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration with ectopic expression of DNER antigen on Reed-Sternberg cells. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022;22:e124-e127.

52. Lee SK, Zabrowski C, Lee MS. Management of diplopia using contact lens. Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2024;49:1-6.

53. Velez FG. A 2020 update on 20/20 X 2 diplopia after ocular surgery: Strabismus following retinal detachment surgery. J Binocul Vis Ocul Motil. 2021;71(4):132-137.

54. Winsløw AE, Winsløw F. [Diplopia and neck pain may be a sign of Lyme neuroborreliosis]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2022;184(11):V09210742.

55. Lee AG. Lecture: Five neuro-ophthalmic diagnoses you cannot afford to miss. March 30, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AnAsw6s9e9g

56. Lee AG, Muayad J, Hussain ZS, et al. Medico-legal aspects of neuro-ophthalmology. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. March 18, 2025. https://eyewiki.org/Medico-Legal_Aspects_of_Neuro-Ophthalmology

57. Watane A, Kalavar M, Chen EM, et al. Medical malpractice lawsuits involving ophthalmology trainees. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(6):938-942.

58. Zhu D, Wong A, Shah PP, Pomeranz HD. Neuro-ophthalmology malpractice: A review of the Westlaw Database. Med Leg J. 2022;90(4):200-205.

59. Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL, Frankel RM. The doctor-patient relationship and malpractice. Lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(12):1365-1370.