Evaluation and Management of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in Nonpregnant Patients: A Detailed Review

August 15, 2025

By Catherine A. Marco, MD, FACEP, and Matthew Turner, MD

Executive Summary

- Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) can cause significant distress, anemia, and disruption to daily life. Early recognition and management in the emergency department are key to preventing complications.

- Preferred terminology includes AUB and heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB). Outdated terms like menorrhagia and metrorrhagia are no longer recommended.

- HMB is defined as > 80 mL blood loss per cycle, or subjective symptoms such as frequent pad changes (every two hours) and/or passage of blood clots.

- Etiologies can be categorized using PALM-COEIN; structural (PALM): polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyoma (fibroids), malignancy/hyperplasia; non-structural (COEIN): coagulopathy, ovulatory dysfunction, endometrial causes, iatrogenic, not yet classified.

- Structural causes can vary significantly in severity. Malignancy must be considered in patients > 45 years of age or with risk factors (e.g., obesity, diabetes, unopposed estrogen).

- Non-structural causes are common in younger patients. Up to 20% of adolescents with HMB have an underlying coagulopathy (e.g., von Willebrand disease).

- Emergency department evaluation focuses on hemodynamic status, resuscitation, and diagnostic evaluation.

- The emergency department evaluation of AUB and HMB typically includes laboratory evaluation with complete blood count, type and screen, pregnancy testing, coagulation studies, and consideration of imaging such as sonography for the detection of structural etiologies.

- Initial treatment in the emergency department includes intravenous (IV) fluids, blood transfusion if needed, and medications such as tranexamic acid and/or IV estrogen for severe bleeding.

- In cases of refractory or massive bleeding, balloon tamponade or gynecological and/or interventional radiology consultation may be necessary for procedural or surgical management.

- Outpatient therapies can include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hormonal agents such as oral contraceptives, and possible iron supplementation if the patient has evidence of iron deficiency.

- Timely gynecology follow-up is essential to assess for persistent bleeding, need for further imaging and/or biopsy, and to establish a long-term management plan.

Abnormal vaginal bleeding accounts for 598,000 emergency department (ED) visits in the United States annually and comprises approximately 0.4% of ED visits.1 Vaginal bleeding in the nonpregnant patient may be due to various etiologies, including structural abnormalities, dysfunctional bleeding, disorders of menstruation, trauma, or coagulopathy. ED assessment and management includes a thorough history and physical examination, stabilization, diagnostic studies, treatment, and appropriate disposition.

Menstruation

Education regarding menstruation for women is highly variable; although it is a natural process, menstruation remains associated with a high degree of stigma.2 “Period poverty,” defined as the unaffordability and inaccessibility of menstrual products to segments of the population, further complicates the issue.3 Given its critical role in reproduction and the health of half of the population, physicians should be familiar with the physiology of menstruation.4

In the proliferative phase of menstruation, the endometrial tissue develops and rapidly grows, triggered by a significant outpouring of estradiol.4 As this occurs, the ovaries experience their follicular phase, and begin to form a corpus luteum, with secretion of progesterone. This leads into the secretory phase of menstruation, where progesterone maintains the endometrial lining to facilitate pregnancy.4 If pregnancy does not occur, progesterone levels drop precipitously, leading to the initiation of menstruation. In this process, inflammatory mediators increase, leading to increased vessel permeability, endometrial blood flow, and ultimately breakdown of the endometrial tissue, presenting as menstrual bleeding.4 Interestingly, humans, Old World primates, fruit bats, spiny mice, and elephant shrews are the only species known to menstruate.4 Other mammals have an estrous cycle in which the uterine lining is reabsorbed rather than shed in menstruation.

In recent years, there has been a push in the literature to replace terms such as “dysfunctional uterine bleeding” and “menorrhagia” with the more precise terms “abnormal uterine bleeding” and “heavy menstrual bleeding.”5

Heavy Menstrual Bleeding and Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Over the course of a woman’s reproductive lifetime (from menarche to menopause), the average woman will experience approximately 400 menstrual cycles, typically occurring every 28 days, with bleeding lasting about four to five days as the uterus sheds its endometrial lining.6 However, there is significant variability in length and duration of cycles as well as the degree of bleeding. Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) can be defined as excessive bleeding that ultimately leads to negative social, economic, emotional, and health consequences for the patient, reducing their quality of life.7 The global incidence has been estimated to range as high as 77.6% in some populations; approximately 50% of women of reproductive age have reported experiencing HMB.8,9 It is more common in women in the perimenopausal period.6 Traditionally, HMB was defined quantitatively as more than 80 mL of bleeding per menstrual cycle.6 However, while this is difficult to quantify in the ED setting, a thorough history can help determine this. Patients who self-report “very heavy” menstrual bleeding have a reported sensitivity and specificity of 74% for predicting HMB.7 HMB also may be defined as saturating a tampon more frequently than every two hours, or a sensation of flooding around tampons.7 Other methods, such as a pictorial bleeding assessment chart, may provide similar estimates of HMB based on product use.7

However, defining HMB by tampon use also is problematic, given the variety of products currently offered in the menstrual hygiene market. Internal absorbent products include tampons and sponges, but external absorbent products, specifically disposable pads, are convenient and preferred by the majority of patients.7 A fully saturated pad may hold anywhere between 5 mL and 15 mL of blood, with significant variation between different brands.7 Other hygiene products include internal reservoirs, such as menstrual cups and discs.7 In low-resource settings, patients may resort to cloth materials and may be significantly affected by a lack of infrastructure for hygiene, privacy, and disposal of menstrual products.8 Even in high-resource settings such as the United States, HMB may have an annual cost of more than $2,000 per patient, due to a combination of menstrual products and work absences.9

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is a common presentation in the ED, with approximately 1.03 million visits to U.S. EDs in 2016 alone for AUB-related complaints.10 Although there is significant overlap with a diagnosis of HMB, AUB also applies to patients who experience bleeding outside of the fifth to 95th percentile of the population in terms of menstrual frequency, regularity, and duration in addition to volume.11 AUB can be difficult to define and may be classified using the information in Table 1.

Table 1. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Definitions |

Menstrual Frequency

Menstrual Regularity

Volume

|

Adapted from: Wouk N, Helton M. Abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(7):435-443. |

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Patients presenting with HMB/AUB should have a thorough medical history and physical examination taken.12 Patients should be assessed rapidly for any evidence of hemodynamic instability or anemia, and should have a pregnancy test conducted.11 If the patient is stable, a thorough history should be taken regarding the patient’s bleeding pattern, including the volume, frequency, duration, and regularity of the bleeding. Any family history of bleeding disorders and bruising, epistaxis, and bleeding following dental procedures should be obtained to determine any possibility of a genetic coagulopathy.11 Systemic diseases, such as diabetes and malignancy, should be identified. Any medications, contraceptives, blood thinners, or hormone treatments that the patient uses should be identified.13 Menstrual history also should be determined, along with the effect of menstruation on the patient’s quality of life, such as days of school or work missed.14 Recent pregnancies, vaginal deliveries, or vaginal instrumentation also should be identified. Any history of syncope, presyncope, or orthostatic hypotension should be determined, since this may indicate underlying hemodynamic instability.14

The physical examination should include a thorough examination of the pelvis with both speculum and bimanual examinations. Since bleeding from the urethra, perineum, and anus can be mistakenly identified as vaginal bleeding, these areas should be assessed as well, particularly if the patient has difficulty communicating.11 The physical examination can be extremely helpful in diagnosis. A soft or enlarged uterus may indicate leiomyosis or adenomyosis; cervical/adnexal tenderness may indicate pelvic inflammatory disease; and the presence of acne, hirsutism, and hyperandrogenic features may indicate polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS).13 Of note, pelvic examinations may be deferred initially in adolescents if there is no concern for sexually transmitted infection (STI) and trauma, and if they respond well to treatment.11 Current guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) only recommends pelvic examinations in patients younger than 21 years of age if they are medically indicated.15 However, an examination of the external genitals and rectum still should be performed in pediatric patients, employing a frog-leg position, knee-chest position or lithotomy position.16

Laboratory testing should include a serum or urine pregnancy test, complete blood count, and an iron panel in cases of concern for anemia.11,12 A type and screen for a possible blood transfusion also should be performed in cases of significant bleeding, laboratory evidence of anemia, or hemodynamic instability.17 Additional testing, including thyroid function tests, prolactin levels, platelet counts, prothrombin times, partial thromboplastin times, and additional coagulopathy laboratory tests may be considered on an individual basis if indicated.11,12 Because of the possibility of endometrial cancer, any patient older than age 45 years presenting with AUB should be referred to gynecological services for possible endometrial sampling.11 Other laboratory tests to consider include chlamydia and STI testing when an underlying infection is suspected.17

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics has approved the use of the PALM-COEIN classification to determine the causes of AUB. This system also can be applied to HMB.6 PALM refers to structural causes (polyp, adenomyosis, leiomyoma, malignancy, and hyperplasia), while COEIN refers to nonstructural causes, such as coagulopathies, ovulatory dysfunction, endometrial abnormalities, iatrogenic causes, and not otherwise classified etiologies.11 (See Table 2.)

Table 2. PALM-COEIN Classification |

P: polyps A: adenomyosis L: leiomyoma M: malignancy and hyperplasia C: coagulopathies O: ovulatory dysfunction E: endometrial causes I: iatrogenic causes N: not yet classified causes |

Adapted from: Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Broder MS, et al. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;113:3-13. |

Structural Causes

Structural causes of HMB and AUB include polyps, fibroids, and malignancies.8 These are covered under the PALM (polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyoma, and malignancy) section of the PALM-COEIN acronym.6

Polyps

Polyps, defined as abnormal outgrowths of either endometrial or myometrial tissue in the uterus, are one of the primary causes of HMB. Endometrial polyps have an estimated incidence of up to 28% of women and are most common in the fifth decade of life.6 They appear to be stimulated by estrogen and are associated with medications such as tamoxifen that activate estrogen receptors in the uterus.6 Endometrial polyps appear to cause HMB due to incomplete shedding of the endometrium during menstruation, as well as possible changes to the microvasculature that they cause to the uterus.6 While the vast majority of polyps are benign, there is a slight risk of development into endometrial malignancy, with risk factors for this including age, post-menopause, obesity, diabetes, use of tamoxifen, and AUB.18 Diagnosis often is made through transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), which has a sensitivity from 19% to 96% and a specificity of approximately 53% to 100%.18 The use of Doppler flow techniques and either saline or gel infusion into the uterus, which allow for better contrast and detection, may significantly improve the diagnostic quality of TVUS.18 Ultimately, the gold standard for polyp diagnosis is hysteroscopy and biopsy, which should be done outside an ED setting. Likewise, the ultimate treatment for polyps is polypectomy, which typically is performed by a gynecologist.18 In asymptomatic postmenopausal women, removal typically is recommended for polyps greater than 2 cm or in the presence of risk factors for endometrial carcinoma (e.g., obesity, hypertension, diabetes, tamoxifen use). In asymptomatic premenopausal women, expectant management may be considered, especially for small polyps (< 1 cm), since spontaneous regression is possible and the risk of malignancy is low.19 Data do not support any type of medical treatment of polyps.18

Although polyps may cause HMB, they are more likely to cause AUB in the form of breakthrough bleeding between menses.11 Breakthrough bleeding is considered unscheduled vaginal bleeding outside of regularly scheduled menses.20 Unless they are prolapsed through the cervix, they are unlikely to be seen on physical exam.11 Unfortunately, recent research has indicated racial disparities in the diagnosis of AUB in American EDs. Black women in particular are less likely to have a diagnostic ultrasound ordered than white women, and also are significantly less likely to be referred to gynecology for outpatient follow-up. Similarly, perimenopausal women are less likely to have ultrasounds performed and follow-up referrals ordered.21

Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis is another common disorder, caused by hyperestrogenism that leads to endometrial tissue infiltrating into the myometrial smooth muscle of the uterus.22 Up to one-third of cases are asymptomatic, but the majority of patients experience HMB/AUB as well as dyspareunia and enlargement and tenderness to the uterus.6,11 This condition appears to be most common in multiparous perimenopausal women, although there appears to be a familial component as well.6 Patients may display a dense and enlarged uterus on physical exam.11 Diagnosis may be made through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or TVUS.6 TVUS often shows a globally enlarged uterus, uterine wall asymmetry, and significantly increased vascularity.23 Adenomyosis may be treated conservatively. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have demonstrated some moderate effectiveness at treating the pain and discomfort of HMB associated with adenomyosis. However, progestins tend to be more effective treatments, since they suppress the body’s secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) and reduce the hyperestrogenism that contributes to adenomyosis. Dienogost, an oral progestin, has been shown to reduce both the pain and anemia associated with HMB secondary to adenomyosis. Other treatments include subcutaneous progestin, and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD), an intrauterine device (IUD) designed to release progestin directly into the uterus.22 In severe cases, patients may require surgery or even interventions such as uterine artery embolization.22 TVUS is the first-line imaging modality for diagnosis, although MRI also may be used.24

Leiomyomas

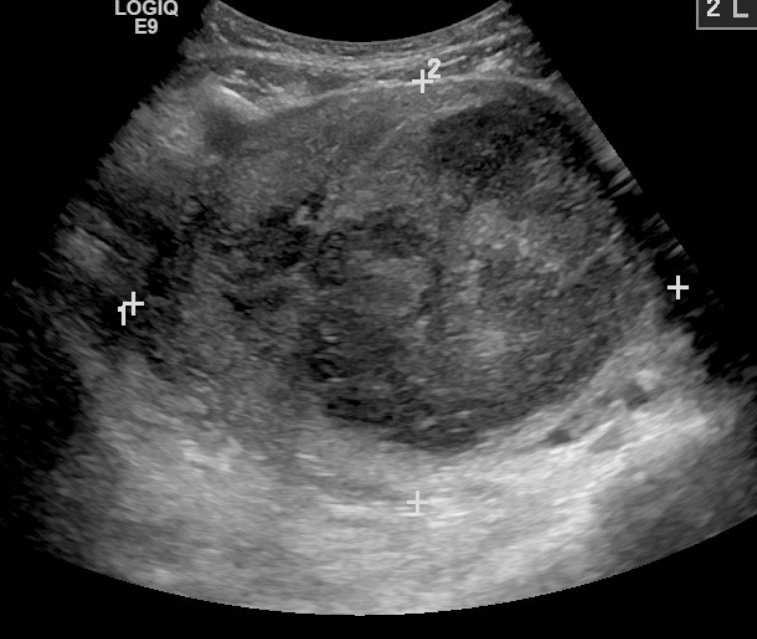

Leiomyomas, also known as fibroids, are benign and often asymptomatic neoplasms of the myometrium. Incidence peaks in the fifth decade of life. There appears to be a strong genetic component, with obesity as a noted risk factor.6 Other risk factors include Black race, lack of physical activity, smoking, alcohol and caffeine consumption, and nulliparity.24 Although the majority of patients with fibroids are asymptomatic, patients may experience urinary symptoms, congestion, dyspareunia, and constipation in addition to HMB and AUB.6 The size of the leiomyoma appears to have a direct effect on the degree of bleeding.11 Medical management of symptomatic leiomyomas includes gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, such as leuprolide acetate, which remains the gold standard for improving both symptoms and reducing leiomyoma burden in patients.25 Other therapies include NSAIDs, LNG-IUD, and surgical interventions ranging from uterine artery embolization to myomectomy and hysterectomy.24 (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Transvaginal Ultrasound Demonstrating a Leiomyoma |

|

Source: James Heilman, MD, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Malignancy and Hyperplasia

Endometrial malignancy is highly tied to estrogen, since estrogen signals growth and proliferation of the endometrium, and in excess amounts can lead to endometrial tumorigenesis.6 Conversely, progesterone acts as an inhibitor for endometrial growth. Any condition that alters the balance between these two hormones often is associated with endometrial hyperplasia and, thus, an increased risk of malignancy.6 Unopposed secretion of estrogen, which includes states such as PCOS, obesity, nulliparity, diabetes, Lynch syndrome, estrogen therapy, early menarche, late menopause, chronic anovulation, and estrogen-secreting tumors, are significant contributors to endometrial hyperplasia and thus malignancy.6,26 Similarly, medications such as tamoxifen, used for treating breast cancers, is associated with an increase in endometrial hyperplasia and cancers caused by agonism of estrogen receptors.26 In contrast, use of combined oral contraceptives for at least one year and having multiple births are protective factors.27 It should be noted that nearly 70% of patients with endometrial cancer are obese, and that a rising body mass index (BMI) is associated with an increased risk of death.27

Although the majority of endometrial malignancies are due to endometrial hyperplasia, it should be noted that a number of tumors, including uterine serous carcinoma, are not associated with prior endometrial hyperplasia.6 Endometrial carcinomas can produce an increased risk of HMB, but they also are more often associated with an irregular and continuous bleeding presentation and, thus, more likely to present as AUB.6 TVUS is considered a first-line screening tool to assess endometrial thickness, particularly in postmenopausal women with bleeding. (See Figure 2.) An endometrial thickness ≤ 4 mm has a high negative predictive value for endometrial cancer, but a thickened endometrium is not diagnostic and requires histologic evaluation. However, recent studies have shown that it is not a reliable tool for up to 11.4% of cases with endometrial cancer.28 Computed tomography (CT) scans typically are not effective for initial diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma.27 Patients with concerning features for endometrial cancer — such as advanced age, previously mentioned risk factors, and/or a thickened endometrial stripe on TVUS — should be referred to gynecology for further evaluation and endometrial biopsy.28 Ultimately, a conclusive diagnosis depends on biopsy of an endometrial tissue sample.27

Figure 2. Transvaginal Ultrasound Demonstrating a Thickened Endometrial Stripe, Concerning for Endometrial Cancer |

|

Image courtesy of Daniel Migliaccio, MD. |

Older adult women, generally considered patients older than the age of 60 years, presenting with HMB/AUB are more likely to have an underlying diagnosis of malignancy.29 Up to 10% of women with endometrial cancers experience postmenopausal bleeding; postmenopausal women should be assessed closely for any evidence of malignancy.30

Although malignancies may cause HMB, they are more likely to lead to AUB, with vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal women presenting as the most common symptom.27 ACOG recommends that any woman with AUB be evaluated for endometrial malignancy if she is older than 45 years of age, or if there is any history of unopposed estrogen exposure.27 Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, also known as Lynch syndrome, increases the relative risk of endometrial cancer six- to 20-fold.11 Women with Lynch syndrome should keep a menstrual calendar and track any AUB because of their increased risk of endometrial malignancy.27

Non-Structural Causes of HMB/AUB

Non-structural causes of HMB/AUB include coagulopathies, ovulatory dysfunction, endometrial pathologies, iatrogenic causes, and causes that currently are not known.8 They may be considered under the COEIN acronym of the PALM-COEIN mnemonic.6

Coagulopathies

Menstruation is highly dependent on the coagulation pathways, with both platelet aggregation and clot formation.6 Twenty percent of women with HMB have an underlying bleeding disorder.31 Diagnostic tools, such as the Phillips Bleeding Assessment Tool, may be effective in determining the presence of hemostatic disorders in patients with HMB/AUB.14 Up to 13% of women with HMB have von Willebrand disease.6 Other coagulopathies include hemophilia A and B, vitamin K deficiency, and chronic liver disease. Adolescent patients also are more likely to present with platelet function disorders that may contribute to HMB.6 Diagnosis should include a thorough history of bleeding in both the patient and the patient’s family, as well as episodes of bleeding associated with dental work, epistaxis, or post-surgical bleeding.32 In patients with a concerning history for possible coagulopathies, further laboratory testing should be ordered. Von Willebrand disease may be diagnosed with von Willebrand factor (VWF) antigen, measurements of the VWF’s platelet-binding activity, and factor VIII measurements.32

Von Willebrand disease is the most common bleeding disorder, affecting up to 1.3% of the population.32 Although it may be associated with HMB, it is strongly associated with AUB as well.6 Approximately 50% to 92% of women with von Willebrand disease experience symptoms of AUB.32 Other coagulopathies, such as immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), also may contribute to AUB.32

Unfortunately, many coagulopathy disorders are difficult to detect through routine labwork alone, often presenting with normal values for prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and complete blood count (CBC) values. In these cases, the clinician should conduct a thorough history of bruising, bleeding, epistaxis, and any other abnormalities to determine if the patient requires specialized laboratory tests and treatment.32 Von Willebrand disease may be treated with desmopressin, which may be administered through intranasal, intravenous, or subcutaneous forms.14,17 While the optimal dosing schedule of desmopressin for HMB secondary to von Willebrand disease remains unknown, an initial dose at the onset of menses with two additional doses every 24 hours appears to be effective. Intranasal dosing may be given at a single spray of 150 mcg for patients weighing less than 50 kg and a spray of 300 mcg into each nostril for patients weighing more than 50 kg. Intravenous dosages of desmopressin may be given at 0.3 mcg/kg diluted in 50 mL to 100 mL of normal saline for adults, or diluted in 15 mL to 30 mL of normal saline for children. Subcutaneous desmopressin may be simply given at 0.3 mcg/kg.33

Other coagulopathies, such as Glanzmann thrombasthenia, often have unremarkable CBC, PT, and aPTT and, thus, may require specialized testing.32 Other disorders, such as hemophilia, have the potential to increase bleeding risk even in generally asymptomatic carriers. HMB may manifest in women with low normal levels of Factor VIII or Factor IX, and may require genetic testing.34 In cases such as these, the patient should be referred to a hematology specialist. The 52-mg LNG-IUD is the most effective hormonal agent in controlling bleeding in adolescents with coagulopathies.14 Acute bleeding in cases of hemophilia should be treated with repletion of Factor VIII and Factor IX as well as treatment with clotting factor.35

Acquired coagulopathies, such as those seen in conditions such as leukemia, aplastic anemia, renal disease, liver disease, sepsis, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), also should be considered in cases of severe AUB/HMB.12 DIC, also known as consumptive coaguloapathy, has a mortality rate of approximately 40%. Always occurring secondary to an underlying condition, it often is encountered in postpartum women and may be difficult to diagnose. These patients often require massive amounts of blood transfusion.36

Ovulatory Dysfunction

Ovulatory dysfunction is another contributor to HMB, since any disturbance to the body’s hypothalamus, pituitary, and ovary (HPO) axis may result in changes to the menstrual cycle.37 (See Table 3.) PCOS is one of the primary conditions that may cause this, with an estimated incidence of approximately 8% in cases of HMB.6,38 PCOS is one of the most common endocrine disorders in women and is associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, an increase in cardiovascular disease, hypertension, endometrial hyperplasia, and an increase in endometrial cancer. Diagnosis is not dependent on a single test, but rather a constellation of at least two of the following: irregular menses, clinical or chemical evidence of androgen excess, and ultrasound assessment of the ovaries.39 Ultrasound will show enlarged ovaries with multiple small cysts, and it often shows significant thickness of the endometrium as a result of the infrequent menstruation that these patients often experience.37 Management should focus initially on conservative strategies, such as weight management and lifestyle interventions. Combined oral contraceptive pills are effective in treating irregular cycles and hormone imbalances, and they may be combined with metformin for effective treatment of insulin resistance.39

Table 3. Ovulatory and Endocrine Dysfunction Leading to Heavy Menstrual Bleeding37-39 | |

Disorder | Presentation |

PCOS | HMB, AUB, long and irregular cycles |

Diabetes | HMB, prolonged cycles |

Hyperprolactinemia | HMB, AUB |

Hypo- and hyperthyroidism | HMB, AUB, amenorrhea |

Cushing’s syndrome | HMB, AUB |

PCOS: polycystic ovarian syndrome; HMB: heavy menstrual bleeding; AUB: abnormal uterine bleeding | |

Multiple other endocrine abnormalities may result in HMB.37 Thyroid dysfunction, including both hypo- and hyperthyroidism, also may contribute to HMB.38 Generally, hypothyroidism is more likely to present with irregular and heavy menses and breakthrough bleeding, while hyperthyroidism is more likely to present in oligomenorrhea and polymenorrhagia.37 Treatment for hypothyroidism should incorporate levothyroxine therapy, while hyperthyroidism may be treated with anti-thyroid medications, such as methimazole, radioactive iodine treatment, or even surgical correction, which is outside the scope of emergency medicine.37,40 Likewise, hyperprolactinemia may contribute to HMB, in addition to AUB. Hyperprolactinemia may be induced by medication or may be pathological; in either case, it will lead to significant menstrual irregularity, ranging from HMB to AUB to complete amenorrhea. Hyperprolactinemia should be treated with dopamine agonist medications, such as cabergoline, which may restore the normal menstrual cycle.37 Diabetes also may lead to menstrual cycle irregularity, although further research on the effect of diabetes on the menstrual cycle is needed.37

Cushing syndrome may cause HMB.37 Cushing syndrome is caused by prolonged elevation in the body’s cortisol, from either exogenous sources, such as steroids, or endogenous production. Patients often present with a characteristic appearance of a round face, dorsocervical fat pads, purple striae, and facial plethora, although this appearance is not present in all patients.41 Management may require surgery for Cushing disease due to endogenous production of cortisol, removal of exogenous sources of cortisol, or various medical therapies. These patients should be referred to an endocrinologist for specialized care.41

Endometrial Causes

Perimenopause, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the period of time two to eight years before the woman’s final menstrual period and one year after, also generally is included in this category. Ovulation often is irregular, leading to irregular shedding of the endometrium. Patients in this period may experience intermittent amenorrhea followed by AUB. Generally, AUB may be considered part of the body’s normal physiology, although other etiologies should always be ruled out.42 These patients should be assessed using the PALM-COEIN pathway and the evaluation/diagnostic methodologies listed previously.42 When more acute etiologies have been ruled out, these patients often require reassurance as well as follow-up with OB/GYN services.42

Iatrogenic Causes

There are multiple iatrogenic causes that may lead to HMB/AUB. Various contraceptives, including hormonal agents, as well as copper IUDs, may lead to breakthrough bleeding.11 Anticoagulants, including warfarin, heparin, and non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs), also may lead to HMB.12 Various other medications, such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (such as goserelin or leuprorelin), aromatase inhibitors, antidepressants, and antipsychotics, also may contribute to AUB.11,12 Iatrogenic causes also may be surgical, such as vaginal bleeding post-hysterectomy.43 Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), defined as blood loss greater than 500 mL, is a significant cause of death during childbirth and has a reported incidence that ranges from 0.79% to as high as 28.90%. Risk factors include hypertension, obesity, prolonged labor, trauma to the genital tract, and multiple prior pregnancies. Iatrogenic causes here may be the result of lacerations or trauma during vaginal delivery, particularly if forceps or vacuum extractors have been used. While a full discussion of PPH is outside the scope of this paper — meant to focus on nonpregnant vaginal bleeding — emergency medicine physicians should be aware of the “four Ts” of PPH: tone (uterine atony), trauma, tissue (retained clots or placenta), or thrombin (clotting-factor deficiencies).44

The final classification of PALM-COEIN includes not yet classified etiologies. These are the most poorly studied causes of HMB/AUB and include arteriovenous malformation.12 Cesarean scar defects are another cause, where they may cause blood to collect within the uterine cavity, further leading to HMB/AUB.11 Severe cases of bleeding have been known to result from iatrogenic uterine ruptures, such as those caused by intrauterine balloon tamponades.45 Pseudoaneurysm of the uterine artery also may cause life-threatening vaginal bleeding.46 Even sexual intercourse, in the case of vaginal laceration and trauma, has the potential to lead to life-threatening hemorrhagic shock.47 In another unclassified cause, transgender males taking hormone therapy may experience persistent vaginal bleeding for up to three months; this appears to be more common with patients taking transdermal testosterone gel and may require follow-up with a specialized endocrinologist.48

Other Causes of Bleeding

There are a number of other causes of bleeding in nonpregnant women not covered by the PALM-COEIN acronym. It is important for physicians to remember that the uterus is not the only potential source of vaginal bleeding — bleeding from the bladder, urethra, perineum, and anus may incorrectly present as vaginal bleeding.11 In cases such as this, a thorough history and physical exam are essential.

For example, postcoital bleeding often is associated with cervicitis and cervical cancer, and, thus, is not included in PALM-COEIN.11 Endometritis and pelvic inflammatory diseases also may cause AUB.11 Other cases of postmenopausal bleeding are due to urinary tract infections or uterovaginal prolapse.29

Emergent Management

Severe cases of vaginal bleeding, presenting with hemodynamic instability, may require resuscitation and emergent blood transfusions. In cases where the patient has a cumulative blood loss of more than 500 mL, is tachycardic, is hypotensive, or has any other signs of significant hypovolemia, emergent resuscitation with hospital-accepted hemorrhagic shock or “massive transfusion protocols” should be initiated. Because visual identification of blood loss often is inaccurate, if possible, blood-soaked materials and clots may be weighed; large clots also may be transferred to containers to provide further estimates of blood loss. As a general rule, 1 g of weight correlates to approximately 1 mL of lost blood volume. Vital signs should be monitored every five minutes, and blood products should be administered. Tranexamic acid, prothrombin complex concentrates, and fibrinogen also may be considered when resuscitating in hemorrhagic shock secondary to vaginal bleeding. The recommended dosing of tranexamic acid for a patient experiencing large-volume vaginal bleeding that has resulted in shock is 1 g intravenously infused over 10 minutes, with a second 1 g dose if bleeding continues after 30 minutes.49 Patients with large-volume vaginal bleeding should be kept warm to reduce the risk of hypothermia, which can precipitate DIC and potentially worsen the bleeding.50

Balloon tamponade has proven to be highly successful in achieving hemostasis in cases of severe uterine bleeding. Commercial products, such as the ebb Complete Tamponade System, may be effectively employed in the ED.51 Foley catheters also may be used effectively in the absence of these specialized products. ACOG recommends the use of a 26-French Foley catheter, infused with 30 mL of saline, as a possible means to successfully perform tamponade in active bleeding patients.17 In resource-poor settings, the “condom catheter” approach — tying a condom to the end of a Foley or simple rubber tube with sterile string, inserting the condom into the uterus via forceps, and then inflating it with 250 mL to 500 mL of water or normal saline — was successful in achieving hemostasis in 186 out of 193 cases.52 Other products include the Bakri balloon, which also may be used to effectively induce tamponade in cases of PPH.53

Active and significant bleeding also may be treated acutely with 20 mg intravenous (IV) estrogen every four hours until the bleeding slows or ceases.34 Conjugated equine estrogen, at 25 mg IV every four to six hours for 24 hours, also may be used as an effective treatment.17 OB/GYN should be consulted in patients with large-volume vaginal bleeding for further management and anticipated admission. In addition, interventional radiology consultation may be considered for possible transcatheter uterine arterial embolization in patients with severe gynecologic hemorrhage, particularly when initial medical and surgical management is insufficient or contraindicated.54

Non-Emergent Management

In stable patients, the cause of the acute bleeding should be determined so that the most effective treatment strategy can be initiated.17 Potential adjunctive treatment options for stable patients with vaginal bleeding include tranexamic acid, combined oral contraceptives, and medroxyprogesterone contraceptives, all of which are discussed in the following sections.17

As noted earlier, NSAIDs are surprisingly effective at treating both dysmenorrhea and menstrual blood loss. Medications such as naproxen, ibuprofen, and diclofenac, when taken during menstruation, may reduce blood loss by 25% to 35%.55 In cases of chronic AUB, ibuprofen 600 mg every six hours, ibuprofen 800 mg every eight hours, naproxen 250 mg to 500 mg twice daily, and mefenamic acid 500 mg every eight hours, all are effective at treating chronic bleeding.12 There appears to be no significant difference between the various NSAIDs in their effectiveness in treating HMB.55 NSAIDs should be taken with food and should be avoided in patients with underlying bleeding disorders, gastric ulcers, or kidney impairment.12,55

Tranexamic acid is a more effective treatment than NSAIDs for vaginal bleeding.55 Tranexamic acid for the treatment of HMB remains the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved use of the medication.56 Given orally, in formulations ranging from 1,000 mg to 1,300 mg every six to eight hours, it can be given in conjunction with NSAIDs.55 It also may be given in a dosage of 10 mg/kg intravenously for a maximum of 600 mg per IV dose, three times daily.12 When taken orally, tranexamic acid should be taken during days 1-5 of the menstrual cycle. It has been shown to reduce menstrual blood loss by 26% to 50% on average.55 In the acute setting, it also may be given at this same regimen for five days.17 It is a safe and well-tolerated medication; there are few side effects, and no significant evidence that it increases the risk of thromboembolism.55 Given its limited effect on dysmenorrhea, it is recommended to take it with an NSAID.55 In cases of severe vaginal bleeding, such as that seen with postpartum hemorrhage, the WHO recommends 1 g of IV tranexamic acid given as soon as possible, with a second 1 g IV dosage if bleeding continues for another 30 minutes, or if bleeding restarts within 24 hours.57

Hormonal agents also may be employed in HMB/AUB. The 52-mg LNG-IUD is one of the first-line treatments, and acts by continuously releasing a low dose of levonorgestrel. Patients may experience reduced bleeding within several months, and the IUD may remain implanted for up to five years. This treatment currently is the gold standard and appears to be both safer and more reliable than oral hormonal interventions.55 It should be noted that this is outside the scope of practice of emergency medicine; patients requiring this intervention should be referred to OB/GYN services.

Combined estrogen and progestin oral contraceptive pills, while less effective than the LNG-IUD, may reduce menstrual blood loss by 12% to 77%.55 Other hormonal agents include the depot medroxyprogesterone acetate shot, administered either intramuscularly or subcutaneously every three months, or the etonogestrel subdermal implant, which lasts for up to three years.12,55 In the acute setting, patients may be started on a combined oral contraceptive that contains 35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol every eight hours for seven days.17 In patients with chronic bleeding, progestin-only pills, such as medroxyprogesterone or norethindrone, can be administered at 5 mg to 10 mg daily.12 For acute bleeding, patients may be started on a seven-day course of medroxyprogesterone acetate 20 mg every eight hours or norethindrone 20 mg every eight hours.12,17 The potential benefits along with an increased risk of arterial and/or venous thromboembolism with oral contraceptive pills should be discussed with the patient prior to the initiation of these medications.58

Other medical interventions include selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs), which combine with progesterone receptors. The most commonly used of these medications, ulipristal acetate, has shown promising efficacy for reducing menstrual blood loss and for decreasing the size of uterine leiomyomas.55

Hysterectomy is the most definitive treatment for AUB; however, it is a major surgical procedure associated with significant risks, including hemorrhage, infection, thromboembolism, and potential injury to adjacent structures.55 Other surgical interventions include endometrial ablation, hysteroscope-guided removal of endometrial lesions, and uterine artery embolization.55 However, all of these treatment options are outside the scope of practice of emergency medicine physicians and require subspecialty consultation.

Iron Deficiency

HMB is a major contributor to iron deficiency (ID) and iron deficiency anemia (IDA) worldwide.9 Anemia, defined by the WHO as a hemoglobin concentration below 12 g/dL in nonpregnant women, disproportionately affects reproductive-aged women and girls.9 IDA makes up 75% of all anemia cases, and often is the result of excessive iron loss secondary to HMB.9 Symptoms of ID may develop even before IDA, as the body prioritizes heme production over other iron-dependent processes. The symptoms include fatigue, brain fog, weakness, shortness of breath, restless legs, hair loss, insomnia, and even pica, which manifests as the compulsive ingestion of materials such as soil, clay, ice, or uncooked ingredients.9,59 ID and IDA exist on a spectrum, and when combined with HMB, can significantly exacerbate negative health, economic, and social consequences for the patient.9

Unfortunately, ID and IDA often are underdiagnosed, despite estimates that up to 15% of premenopausal women in the United States have ID.9,59 The gold standard test for ID requires bone marrow aspiration and is impractical for an ED setting.59 Thus, serum ferritin is the primary form of diagnosis, but it is limited by unclear thresholds that vary across institutions.9,59 Typically, in healthy women, a ferritin threshold of less than 15 mcg/L is highly specific for ID, although a threshold of less than 30 mcg/L also has been used to indicate possible susceptibility to ID.59 However, ferritin levels can be artificially inflated because of high inflammation or conditions such as obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.59 Serum iron concentration also is limited in its efficacy, since it may be reduced in both ID and inflammation.59 Other developing measurements, such as reticulocyte hemoglobin content and hepcidin concentration, offer promising future measurements but currently are not feasible in most EDs.59 Even in cases of known HMB/AUB, a large proportion of patients do not receive any treatment for ID.60

However, in cases of HMB/AUB in which ID or IDA is suspected, the goal should be to replenish the body’s iron stores and to correct anemia if it is present. Premenopausal, non-pregnant women should consume 18 mg of iron daily.59 Although vegetarian diets provide iron, iron absorption from plant sources is less efficient, and vegetarians are more likely to have ID.59 Oral iron supplementation is the first-line treatment for ID/IDA and typically should be initiated with 100 mg to 200 mg of elemental iron per day.61 However, oral iron often is inhibited by limited absorption, poor patient adherence, and negative side effects, such as black stools, vomiting, abdominal pain, and constipation or diarrhea.61 Newer oral formulations, such as sucrosomial iron, have been shown to have higher bioavailability and fewer negative side effects.61 Other treatments include intravenous iron supplementation. Iron isomaltose can be given in doses of 1,000 mg per infusion. Carboxymaltose iron can be administered intravenously at doses of 15 mg/kg up to a maximum dose of 1,000 mg, diluted in 250 mL of saline and administered over 15 minutes.59,61 Although there is a risk of severe reactions, including anaphylaxis or hypersensitivity reactions, the frequency of this is approximately one in 100,000 administrations.61 There also is no increased risk of infection from intravenous iron, although this should be avoided in sepsis.59 Intravenous iron appears to be a safe treatment for ID/IDA that is refractory to oral iron supplementation. Patients with IDA with low hemoglobin values of less than 7 g/dL to 8 g/dL should be considered for intravenous iron administration.61 Physicians should be aware of the risk of transient hypophosphatemia that occurs after iron transfusions.59

Iron supplementation is effective at reducing the symptoms from ID/IDA that may occur secondary to HMB/AUB, improving both reported fatigue, restless leg symptoms, exercise performance, and even cognitive performance in children.59

Pediatric Bleeding

Unlike adult patients, pediatric patients initially may have a pelvic examination deferred, unless they are sexually active with persistent discharge, bleeding, and amenorrhea/dysmenorrhea.16 Transabdominal ultrasounds are preferred over TVUS and should be performed when the patient has a full bladder to optimize imaging of the ovaries.16 CT imaging and MRI also can be considered as adjunctive imaging modalities; however, it is important to keep as low as reasonably acceptable (ALARA) practices in place in terms of radiation exposure for the evaluation of HMB or AUB in pediatric patients.16

Menarche in adolescents occurs approximately two years after the onset of puberty, which includes a change in body odor, breast development, and pubic hair growth.62 Menarche occurs at a mean age of approximately 12.8 years.62 Any vaginal bleeding before this point is extremely rare and should be thoroughly investigated.62 Potential causes of vaginal bleeding prior to menarche include retained foreign bodies, trauma, precocious puberty, malignancies, dermatological conditions, arteriovenous malformations, hypothyroidism, infection, and sexual abuse.62-64 As in adults, hematuria and rectal bleeding are commonly misinterpreted as vaginal bleeding.64 Retained foreign bodies appear to be a common cause of vaginal bleeding in this population, accounting for an estimated 10% to 18% of cases. These patients often have a bloody/brownish vaginal discharge.62 The most common retained foreign body is toilet paper, which may be removed via gentle irrigation with a small pediatric feeding tube. In another technique, the physician may use a Foley catheter to gently flush the vagina with saline, holding the labia majora together simultaneously. This will distend the vagina and allow for easier visualization of the vaginal cavity to examine for any foreign bodies.

The majority of removed foreign bodies will not require antibiotic coverage afterward.65 In cases of suspected sexual abuse, STI testing is recommended in prepubertal children. Prophylactic treatment is not indicated.66 Child Protective Services should be contacted immediately, and a full abuse workup should be initiated.67

Other common causes include lichen sclerosis, various infections, urethral prolapse, and tumors.64 The majority of prepubertal vaginal infections arise from autoinoculation, so any concurrent diagnosis, such as a recent upper respiratory infection, should raise concern for vulvovaginitis.65 Lichen sclerosis rarely requires biopsy and may be made as a clinical diagnosis, presenting with pruritic, fissured, hypopigmented skin forming a “figure of eight” pattern surrounding the vulva and anus.64 Urethral prolapses are common in this population because of lower estrogen levels, and often are painless, present with vaginal bleeding, and are associated with a history of constipation, chronic cough, and other causes of increased Valsalva pressure.65 The prolapsed urethra often will have a donut-shaped appearance, extending beyond the urethral meatus. Mild cases may be treated with one to two weeks of topical estrogen, but cases complicated by necrosis or urinary retention may require referral or consult for surgical resection.65 Testing for STIs and vulvovaginitis also should be considered, as well as hormonal conditions including hypothyroidism, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and McCune-Albright syndrome. However, many of these patients may require examination under anesthesia and referral to specialized care.64

Nonaccidental trauma (NAT) also should be considered in these patients. Injuries to the perineum and labia are significantly more frequent in straddle-type accidental trauma, while injuries to the hymen are more likely to be associated with sexual abuse than accidental trauma, as well as evidence of injury to the poster fourchette.68,69

In cases of neonates presenting with vaginal bleeding in the first few days of life, no workup is required provided that the neonate has a normal physical examination and the bleeding spontaneously resolves. Bleeding in the neonatal period is the result of the withdrawal of maternal estrogen, leading to ischemia and sloughing in the neonate’s endometrium.65

Adolescents often experience HMB, with an estimated prevalence of 34% to 37%.14 The most common cause of HMB in adolescents is ovulatory dysfunction, due to immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis.14 Anovulation, leading to an absence of progesterone and, thus, an estrogen excess, often leads to HMB in the first two to three years following menarche, and typically resolves by the third year of menstruation.14 However, this should be a diagnosis of exclusion, with other PALM-COEIN etiologies ruled out first.14

After ovulatory dysfunction, coagulopathies are the most common cause of HMB in adolescent patients. Approximately 21% to 46% of adolescent patients with HMB have inherited coagulopathies.14 There is a particularly high incidence of von Willebrand disease in adolescents presenting with HMB.14 Despite increasing awareness of this condition, only 20% of adolescents presenting for HMB are screened for von Willebrand disease.14 Hemophilia and disorders of fibrinogen also may present with abnormal bleeding in adolescents.14

Platelet disorders, including acquired disorders such as immune thrombocytopenic purpura and inherited disorders such as Glanzmann thrombasthenia and Bernard-Soulier syndrome, also are common causes of adolescent HMB.14

Conclusion

Abnormal vaginal bleeding in nonpregnant patients requires a thorough history and physical examination. Although the PALM-COEIN mnemonic is effective, it does not cover the full breadth of differential diagnoses that may be encountered in these patients. Emergency medicine physicians should be aware of the many causes and treatments for this common presentation. In addition, the emergency provider should appreciate the nuances in the resuscitation of a patient presenting with hemorrhagic shock secondary to vaginal bleeding.

Catherine A. Marco, MD, FACEP, is Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Penn State Health, Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA.

Matthew Turner, MD, is Emergency Medicine Resident, Penn State Health, Hershey, PA.

References

1. Cairns C, Kang K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2019 emergency department summary tables. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:115748

2. Ramaiyer M, Lulseged B, Michel R, et al. Menstruation in the USA. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2023;10(4):186-195.

3. VanderMeulen H, Tang GH, Sholzberg M. Tranexamic acid for management of heavy vaginal bleeding: Barriers to access and myths surrounding its use. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2024;8(3):102389.

4. Critchley HOD, Maybin JA, Armstrong GM, Williams AR. Physiology of the endometrium and regulation of menstruation. Physiol Rev. 2020;100(3):1149-1179.

5. Kabra R, Fisher M. Abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescents. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2022;52(5):101185.

6. Hapangama DK, Bulmer JN. Pathophysiology of heavy menstrual bleeding. Women’s Health (Lond). 2016;12(1):3-13.

7. Liberty A, Bannow BS, Matteson K, et al. Menstrual technology innovations and the implications for heavy menstrual bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141(4):666-673.

8. Sinharoy SS, Chery L, Patrick M, et al. Prevalence of heavy menstrual bleeding and associations with physical health and wellbeing in low-income and middle-income countries: A multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(11):e1775-e1784.

9. Munro MG. Heavy menstrual bleeding, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia: Framing the issue. Int J Gynecol Obst. 2023;162:7-13.

10. Grubman J, Hawkins M, Whetstone S, et al. Emergency department visits and emergency-to-inpatient admissions for abnormal uterine bleeding in the USA nationwide. Emerg Med J. 2023;40(5):326-332.

11. Wouk N, Helton M. Abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(7):435-443.

12. Marnach ML, Laughlin-Tommaso SK. Evaluation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2019;94:326-335.

13. Achanna KS, Nanda J. Evaluation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding. Med J Malaysia. 2022;77(3):374-383.

14. Borzutzky C, Jaffray J. Diagnosis and management of heavy menstrual bleeding and bleeding disorders in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(2):186-194.

15. Bryan AF, Chor J. Factors influencing adolescent and young adults’ first pelvic examination experiences: A qualitative study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32(3):278-283.

16. Mentessidou A, Mirilas P. Surgical disorders in pediatric and adolescent gynecology: Vaginal and uterine anomalies. Int J Gynaecol Obst. 2023;160(3):762-770.

17. [No authors listed]. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: Management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(4):891-896.

18. Clark TJ, Stevenson H. Endometrial polyps and abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB-P): What is the relationship, how are they diagnosed and how are they treated? Best Practi Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;40:89-104.

19. Vitale SG, Haimovich S, Laganà AS, et al. Endometrial polyps. An evidence-based diagnosis and management guide. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;260:70-77.

20. Dean J, Kramer KJ, Akbary F, et al. Norethindrone is superior to combined oral contraceptive pills in short-term delay of menses and onset of breakthrough bleeding: A randomized trial. BMC Women’s Health. 2019;19(1):70.

21. Huang W, Ma X, Clark M, Xu X. Diagnostic evaluation for abnormal uterine bleeding at emergency departments in the United States. 2024 American Society of Clinical Oncology Quality Care Symposium. JCO Oncol Pract. 2024;20 (suppl 10; abstr 269). doi: 10.1200/OP.2024.20.10_suppl.269.

22. Stratopoulou CA, Donnez J, Dolmans M-M. Conservative management of uterine adenomyosis: Medical vs. surgical approach. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):4878.

23. Van den Bosch T, Van Schoubroeck D. Ultrasound diagnosis of endometriosis and adenomyosis: State of the art. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:16-24.

24. Mathew RP, Francis S, Jayaram V, Anvarsadath S. Uterine leiomyomas revisited with review of literature. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46(10):4908-4926.

25. Lewis TD, Malik M, Britten J, et al. A comprehensive review of the pharmacologic management of uterine leiomyoma. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018(1):2414609.

26. Nees LK, Heublein S, Steinmacher S, et al. Endometrial hyperplasia as a risk factor of endometrial cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;306(2):407-421.

27. Braun MM, Overbeek-Wager EA, Grumbo RJ. Diagnosis and management of endometrial cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(6):468-474.

28. Doll KM, Pike M, Alson J, et al. Endometrial thickness as diagnostic triage for endometrial cancer among Black individuals. JAMA Oncol. 2024;10(8):1068-1076.

29. Sultana F, Lia LN, Kheya AK, et al. Spectrum of gynecological disorder in geriatric women: A tertiary care centre study. Arch Microbiol Immunol. 2024;8:01-09.

30. Jo HC, Baek JC, Park JE, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and causes of postmenopausal bleeding in older patients. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2018;22(4):189.

31. Davies J, Kadir RA. Heavy menstrual bleeding: An update on management. Thrombosis Res. 2017;151(Suppl 1):S70-S77.

32. Kontogiannis A, Matsas A, Valsami S, et al. Primary hemostasis disorders as a cause of heavy menstrual bleeding in women of reproductive age. J Clin Med. 2023;12(17):5702.

33. Özgönenel B, Rajpurkar M, Lusher JM. How do you treat bleeding disorders with desmopressin? Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(977):159-163.

34. Davila J, Alderman EM. Heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescent girls. Pediatric Ann. 2020;49(4):e163-e169.

35. Sahu S, Lata I, Singh S, Kumar M. Revisiting hemophilia management in acute medicine. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2011;4(2):292-298.

36. Goksever Celik H, Celik E, Ozdemir I, et al. Is blood transfusion necessary in all patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation associated postpartum hemorrhage? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32(6):1004-1008.

37. Naz MSG, Dovom MR, Tehrani FR. The menstrual disturbances in endocrine disorders: A narrative review. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2020;18(4):e106694.

38. Comishen KJ, Bhatt M, Yeung K, et al. Etiology and diagnosis of heavy menstrual bleeding among adolescent and adult patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. J Thromb Haemost. 2025;23(3):863-876.

39. Hoeger KM, Dokras A, Piltonen T. Update on PCOS: Consequences, challenges, and guiding treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(3):e1071-e1083.

40. Lee SY, Pearce EN. Hyperthyroidism: A review. JAMA. 2023;330(15):1472-1483.

41. Reincke M, Fleseriu M. Cushing syndrome: A review. JAMA. 2023;330(2):170-181.

42. Dreisler E, Frandsen CS, Ulrich L. Perimenopausal abnormal uterine bleeding. Maturitas. 2024;184:107944.

43. Cipres DT, Shim JY, Grimstad FW. Postoperative vaginal bleeding concerns after gender-affirming hysterectomy in transgender adolescents and young adults on testosterone. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2023;36(1):33-38.

44. Huang CR, Xue B, Gao Y, et al. Incidence and risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal delivery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023;49(7):1663-1676.

45. Nguyen KT, Lozada MJ, Gorrindo P, Peralta FM. Massive hemorrhage from suspected iatrogenic uterine rupture. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(6):1494-1497.

46. Jennings L, Presley B, Krywko D. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm: A life-threatening cause of vaginal bleeding in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2019;56(3):327-331.

47. Jeng C-J, Wang L-R. Vaginal laceration and hemorrhagic shock during consensual sexual intercourse. J Sex Marital Ther. 2007;33(3):249-253.

48. Defreyne J, Vanwonterghem Y, Collet S, et al. Vaginal bleeding and spotting in transgender men after initiation of testosterone therapy: A prospective cohort study (ENIGI). Int J Transgend Health. 2020;21(2):163-175.

49. Hwang DS, Myers L. Management of postpartum hemorrhage: Recommendations from FIGO. Am Fam Physician. 2023;107:438-440.

50. Wilbeck J, Hoffman JW, Schorn MN. Postpartum hemorrhage: Emergency management for uncontrolled vaginal bleeding. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2022;44(3):213-219.

51. McQuivey RW, Block JE, Massaro RA. ebb® Complete Tamponade System: Effective hemostasis for postpartum hemorrhage. Med Devices (Auckl). 2018;11:57-63.

52. Tindell K, Garfinkel R, Abu-Haydar E, et al. Uterine balloon tamponade for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage in resource-poor settings: A systematic review. BJOG. 2013;120(1):5-14.

53. Said Ali A, Faraag E, Mohammed M, et al. The safety and effectiveness of Bakri balloon in the management of postpartum hemorrhage: A systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;34(2):300-307.

54. Katz MD, Sugay SB, Walker DK, et al. Beyond hemostasis: Spectrum of gynecologic and obstetric indications for transcatheter embolization. Radiographics. 2012;32(6):1713-1731.

55. MacGregor B, Munro MG, Lumsden MA. Therapeutic options for the management of abnormal uterine bleeding. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2023;162 (Suppl 2):43-57.

56. Cai J, Ribkoff J, Olson S, et al. The many roles of tranexamic acid: An overview of the clinical indications for TXA in medical and surgical patients. Eur J Haematol. 2020;104(2):79-87.

57. Roberts I, Brenner A, Shakur-Still H. Tranexamic acid for bleeding: Much more than a treatment for postpartum hemorrhage. Ame J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5(2):100722.

58. Teal S, Edelman A. Contraception selection, effectiveness, and adverse effects: A review. JAMA. 2021;326(24):2507-2518.

59. Pasricha S-R, Tye-Din J, Muckenthaler MU, Swinkels DW. Iron deficiency. Lancet. 2021;397(10270):233-248.

60. Leal CR, Vannuccini S, Jain V, et al. Abnormal uterine bleeding: The well-known and the hidden face. J Endometr Uterine Disord. 2024;6:100071.

61. Cappellini MD, Santini V, Braxs C, Shander A. Iron metabolism and iron deficiency anemia in women. Fertil Steril. 2022;118(4):607-614.

62. Ng SM, Apperley LJ, Upradrasta S, Natarajan A. Vaginal bleeding in pre-pubertal females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020;33(4):339-342.

63. Gershman ML, Simms-Cendan J. Vaginal bleeding in prepubertal females: A case of Shigella vaginitis and review of literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(8):e251303.

64. Moore Y, Hopkinshaw B, Arrowsmith B, et al. Genital bleeding in prepubertal girls: A systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2025;110(5):358-362.

65. Kliegman R, Toth H, Bordini BJ, Basel DG. Nelson Pediatric Symptom-Based Diagnosis: Common Diseases and their Mimics. 2nd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2022.

66. Hoehn EF, Overmann KM, Fananapazir N, et al. Improving emergency department care for pediatric victims of sexual abuse. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20181811.

67. Solís-García G, Marañón R, Muñoz MM, et al. [Child abuse in the emergency department: Epidemiology, management, and follow-up]. An Pediatr (Engl Ed). 2019;91(1):37-41.

68. Iqbal CW, Jrebi NY, Zielinski MD, et al. Patterns of accidental genital trauma in young girls and indications for operative management. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(5):930-933.

69. McIntosh N, Mok JYQ. A comparison of accidental and abusive ano-genital injury in children: Comparison of ano-genital injuries. Child Abuse Rev. 2017;26(3):230-244.